Smallest Black Hole Found

Updated at 2:20 p.m. ET.

NASAscientists have identified the smallest, lightest black hole yet found.

The newlightweight record-holder weighs in at about 3.8 times the mass of our sun andis only 15 miles (24 kilometers) in diameter.

"Thisblack hole is really pushing the limits," said study team leader NikolaiShaposhnikov of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "Formany years astronomers have wanted to know the smallest possible size of ablack hole, and this little guy is a big step toward answering thatquestion."

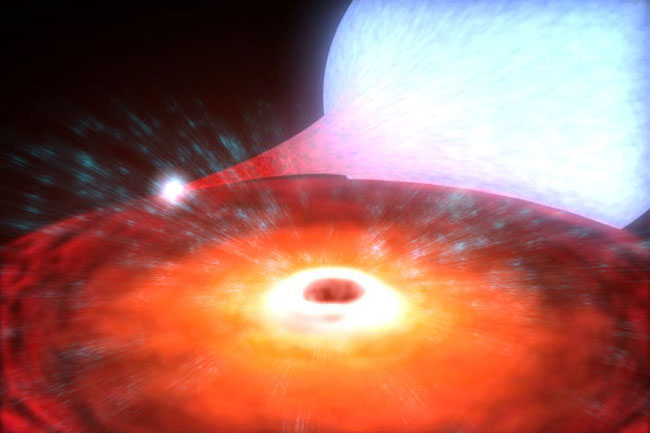

Thelow-mass blackhole sits in a binary system in our galaxy known as XTE J1650-500 in thesouthern hemisphere constellation Ara. NASA's Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer(RXTE) satellite discovered the system in 2001, and astronomers soon realizedthat the system harbored a relatively lightweight black hole. But the blackhole's mass had never been precisely measured.

Black holescan't be seen, but they're identified by the activity around them, which alsohelps astronomers estimate a size of the region inside the activity, and howmuch mass must be in that confined region to generate all the surroundingactivity. More specifically, astronomers can weigh black holes by using arelationship between the apparent size of the black hole and the X-rays emittedby the torrent of gas that swirls into the black hole's disk from its companionstar.

As the gaspiles up near the black hole, it "becomes very dense and congested,"like a traffic jam, Shaposhnikov said at a press conference announcing thefind. "So matter has to literally squeeze into the black hole."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As it issqueezed, the gas heats up and radiates X-rays. The intensity of the X-raysvaries in a pattern repeated over a nearly regular interval. Astronomers havelong suspected that the frequency of this signal, called the quasi-periodicoscillation, or QPO, depends on the mass of the black hole.

As theblack hole gets bigger, the zone of swirling gas is pushed farther out, so theQPO ticks away slowly. But for smaller black holes, the gas sits closer in andthe QPO ticks rapidly.

Shaposhnikovand his colleague Lev Titarchuk of George Mason University used this methodto "weigh" XTE J1650-500 and found a mass of 3.8 suns. This valueis well below the previous record holder GRO 1655-40, which tips the scales atabout 6.3 suns.

This new ?massmeasurement could help shed light on what the smallest star that will produce ablack hole is. Astronomers know that some unknown critical threshold, possiblybetween 1.7 and 2.7 solar masses, marks the boundary between a star that generatesa black hole upon its death and one that produces a neutron star.

"Thisnew result brings us much closer to the theoretically predicted limit,"Shaposhnikov said.

Knowingthis boundary would help scientists understand the behavior of matter when itis scrunched to extraordinarily high densities.

"Thequestion of black hole masses has concerned us for more than a decade now,"said astrophysicist Vicky Kalogera of Northwestern University, who was notinvolved with the study, during the press conference. Scientists had predictedthat there should be more black holes at the lower end of the mass range thanastronomers had identified, so this study helps clear up some confusion as towhere these lightweight black holes were, she added.

Kalogeradid caution that the method used by Shaposhnikov and Titarchuk is not the mainway that black hole masses are measured, but noted that their measurements ofthe masses of other black holes agreed well with the results from the standardmethod.

Shaposhnikovand Titarchuk presented their findings on March 31 at the American AstronomicalSociety's High-Energy Astrophysics Division meeting in Los Angeles.

- Video: Black Hole: Warping Time & Space

- Top 10: The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- Vote: The Strangest Things in Space

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.