Roaring Jets of Carbon Dioxide Solve Mars Mystery

Peculiar spots, fan-like markings, and spider-shaped features on Mars' southern ice cap are seasonal formations, researchers announced today.

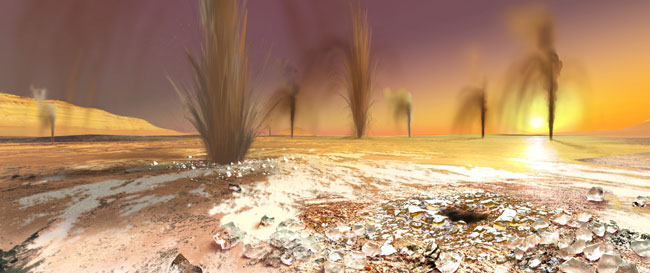

The shapes [see Images] are formed by thin layers of dark dusty material that are sprayed by roaring jets of carbon dioxide that erupt through the ice cap.

This dusty material may also be the reason that the southern ice cap doesn't reflect much light.

Strange spots

The mystery markings, generally 50 to 150 feet wide, appear every southern spring as the Sun rises over the red planet's ice cap. They last about three to four months.

"Originally, scientists thought the spots were patches of warm, bare ground exposed as the ice disappeared," said study co-author Philip Christensen of Arizona State University. But observations made with the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS), a multi-wavelength camera on NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter, revealed that the spots were nearly as cold as the carbon dioxide ice, which along with water ice, make up the ice caps.

With more than 200 visible and infrared images from THEMIS, Christensen and his team studied an area of the southern ice cap from the end of winter in that region through the middle of summer.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

They watched how the spots appeared and developed into fan shaped markings and "spider's" grooves eroded into the surface under ice. Their finding is detailed in the Aug. 17 issue of the journal Nature.

Chilly formations

The whole process begins during Mars' frigid Antarctic winter, when temperatures drop to minus 200 degrees Fahrenheit. It's so cold that the Martian air-95 percent carbon dioxide ?] freezes directly onto the surface of the permanent polar cap, which is made of water ice covered with layers of dust and sand, Christensen explained.

This layer of dusty carbon dioxide frost re-crystallizes, becomes denser throughout winter and starts to slowly sink into the frost.

By spring, the frost layer becomes a slab of semi-transparent ice of about 3 feet thick, sitting on a layer of dark sand and dust. Sunlight passing through the slab reaches the dark material and warms it enough that the ice touching the ground turns directly to gas without going through the liquid phase. This process is called sublimation.

100 mph jets

The warmed material produces a reservoir of pressurized gas under the slab, lifting it off the ground. The weak spots in the slab break through and high-pressure gas shoot up at speeds of almost 100 mph carrying loose sand and particles into the Martian air, the researchers propose.

The large particles, too heavy to go far, land around the vents to make the spots, while the lighter sand grains blow downwind, creating the fans that scientists see.

The lightest pieces drift away to form a thin layer of dust.

"It's like separating wheat and chaff," Christensen said. "The finest-grained materials are carried off by the wind, while coarser grains are sifted again and again, year after year."

The jets continue to erupt until the entire ice slab sublimates and vanishes. This entire process will repeat again at the end of the following winter.

Unclear slab of ice

In a related study reported in this week's journal Nature, the low reflectivity of the southern ice cap is also attributed to the dust in the region. Scientists initially thought this might be because the region is ice-free.

But the mystery deepened when temperature measurements obtained the Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES) on board the Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft revealed that this dark region was nearly as cold as the bright regions surrounding it, said lead study author Yves Langevin from Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale, Orsay, France.

The next thought was that the ice is so see through that the ground can be seen and thus there is reduced reflectivity.

What we observed is that light rays don't penetrate deeply into carbon dioxide ice, hence the "clear slab" idea must be revised, Langevin explained. What is needed is a layer of carbon dioxide (CO2) ice with heavy surface contamination by dust.

"This dust can be either carried into the region from a large basin called "Hellas" by winds (then later carried away) or brought to the surface by CO2 gas bubbles building up below the ice layer, then blowing up," Langevin told SPACE.com.

- Gallery: Ice on Mars

- Mars Ice is Mostly Water: Good for Biologists, Bad for Terraformers

- Mars Mystery: Strange Spirals in Ice Caps Explained

- Icy Shapes on Mars Reveal Two Climates

- VOTE: The Best of Mars Rovers

- Mars in 3-D, Water Included