Japan Launches Asteroid-chasing Probe to Bring Space Rock Samples to Earth

A Japanese spacecraft has launched on an ambitious mission to blast a hole in an asteroid and return samples of the space rock back to Earth.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's (JAXA) Hayabusa2 asteroid mission blasted off Tuesday (Dec. 2) at 11:22 p.m. EST (0422 GMT Dec. 3) from the country's Tanegashima Space Center, where the local time at liftoff was 1:22 p.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 3. If all goes well, the spacecraft should return samples of the asteroid 1999 JU3 to Earth in late 2020, JAXA officials said.

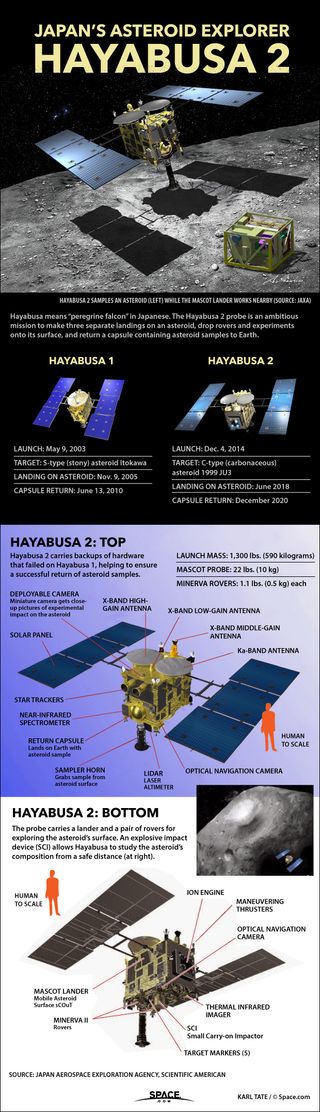

Hayabusa2 is JAXA's bigger, bolder follow-up to its historic Hayabusa mission, which brought the first pristine samples of an asteroid to Earth in 2010 after its own seven-year mission. [Photos of Japan's Hayabusa2 Asteroid Mission]

Like its predecessor, Hayabusa2 will use an ion engine to catch up with its target asteroid, and will also collect space rock samples and return them to a landing site in the Australian outback. But where the first Hayabusa mission only managed to retrieve a tiny amount of asteroid material, Hayabusa 2 is designed to get more out of its space rock visit.

Asteroid 1999 JU3 is a so-called carbonaceous, or C-type, space rock — a different type of asteroid than the rocky (S-type) asteroid Itokawa visited by the first Hayabusa. Scientists suspect asteroid 1999 JU3 holds water and organic materials — some of the building blocks of the solar system.

"Minerals and seawater which form the Earth as well as materials for life are believed to be strongly connected in the primitive solar nebula in the early solar system," JAXA wrote in a description of the mission. "Thus we expect to clarify the origin of life by analyzing samples acquired from a primordial celestial body such as [this] asteroid to study organic matter and water in the solar system, and how they coexist while affecting each other."

In order to reach asteroid 1999 JU3, Hayabusa2 will conduct an Earth flyby in 2015 to pick up speed, then aim for a rendezvous with its target space rock in 2018. Hayabusa 2 is expected to orbit the asteroid for 18 months, landing three times to pick up sample material.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While Hayabusa2 studies asteroid 1999 JU3 from orbit, it will deploy three rovers and a German/European lander called MASCOT, all of which will work independently on the surface to gather information on the asteroid's composition and history.

Long and ambitious mission

Hayabusa2's development costs are pegged at 16.2 billion yen ($136.5 million), with numerous improvements over its predecessor's mission to asteroid Itokawa. (Hayabusa means "Falcon" in Japanese.)

Hayabusa2's ion engines have 20 percent more propulsive force than the first Hayabusa, which launched in 2003. Hayabusa2's scientific observations will take 18 months, rather than just three months. And while its basic design is similar to Hayabusa, the new Hayabusa2 asteroid mission has more sophisticated instruments aboard to study its target asteroid, according to a JAXA mission description.

"The configuration of Hayabusa 2 is basically the same as that of Hayabusa, but we will modify some parts by introducing novel technologies that evolved after the Hayabusa era," JAXA officials wrote. "For example, the antenna for Hayabusa was in a parabolic shape, but the one for Hayabusa 2 will be flattened." [Our Solar System: A Photo Tour]

The design improvement will allow the spacecraft to save weight, officials added. "Thanks to the flat design, the weight of the antenna is reduced to one-fourth compared to a parabolic antenna, whose performance is the same. A lighter antenna is better for a space explorer, thus the flat one is preferable. In addition, it is less easily heated than a parabolic antenna."

Those new instruments include two tools that will search for water: a near-infrared spectrometer and thermal infrared imager. Hayabusa2 will also carry a small impactor that will strike the surface deliberately as the main orbiter watches from above. The impact should allow scientists to see what happens immediately after a crater is formed. Hayabusa 2 is then expected to land on the impact site to collect samples of the subsurface material excavated in the blast.

Hayabusa2 will use a target marker it will drop to the surface of asteroid 1999 JU3 to help guide its descents to the space rock. Using a laser altimeter, the spacecraft will communicate with the marker to find a spot to land on the surface.

The armchair-sized spacecraft is also equipped with star trackers to determine its location in space and orientation, three optical navigation cameras, and multiple antennas — ranging from high- to low-gain — to make sure it can stay in touch with Earth during all phases of the mission.

Asteroid exploration

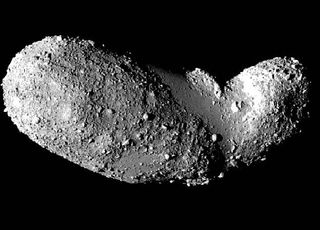

Little is known about 1999 JU3 because its low albedo (reflectivity) makes it difficult to gauge its shape and spin. Astronomers estimate that the asteroid is about 2,952 feet (900 meters) across and that it rotates once every 7.6 hours.

Whatever the Hayabusa2 mission learns will help researchers better understand the early days of the solar system, JAXA officials say.

"An asteroid is considered to have information about the birth of the solar system and its later evolution," JAXA officials wrote in a mission description. "For a large celestial body such as Earth, its original materials were melted once, and consequently there is no way to reach the history before melting. On the other hand, most of the hundreds of thousands of asteroids and comets which we found at this point preserve history of the place and era of their birth within the solar system."

The spacecraft will make three landings by itself, each time putting the material collected in a separate chamber for return to Earth. Meanwhile, three rovers (collectively called Minerva II) and the small MASCOT lander will transmit information from the surface to Hayabusa2.

The rovers will hop around the surface to do exploration, according to JAXA, while MASCOT will only bounce once. MASCOT was created by the French space agency CNES and German space agency DLR.

After completing operations at 1999 JU3, Hayabusa2 will then make the one-year journey back to Earth for an expected landing in the Australian outback late in 2020.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace