Mars Is a Spacecraft Graveyard

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Mars has been a popular target for unmanned spacecraft sincethe dawn of the space age. Numerous attempts have been made to set human-builtprobes into orbit around the red planet and land them on its surface to findout more about our ruddy neighbor, particularly if it carried signs of life.

The first attempt to send a probe to the red planet was madeby the USSR in 1960 with the "Marsnik" spacecraft. While that firsttry, and many subsequent ones, were unsuccessful ? some missed the planet, somewere destroyed during launch, some malfunctioned after launch ? at total of sixlanders or rovers and nine orbiters have been sent to Mars.

Of those successes, only three orbiters and two rovers arecurrently still probing the planet. The spacecraft that have ended theirmissions ? from the first success of Mariner 9 to the most recent mission inthe Phoenix Mars Lander ? remain dormant in orbits circling the planet orsilent at the spot where they landed on the surface.

Phoenix is the latest craft to join the long list in the Mars robotic graveyard. NASA has been listening for signals of life from, but as of today had heard none.

Some of the failures, such as the Mars Climate Orbiter andtwo Soviet landers, also have their graves on Mars.

Here, SPACE.com takes a look at the deadspacecraft of Mars and their missions, whether completed or ended beforethey could begin.

Phoenix Mars Lander

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

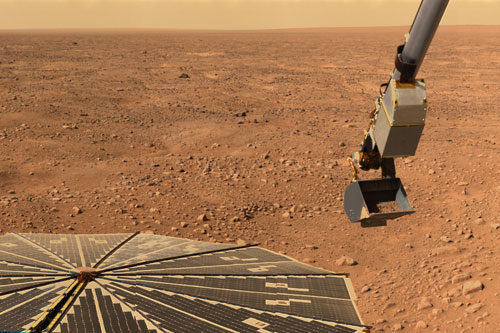

The youngest of all spacecraft at Mars, NASA's PhoenixMars Lander landed in the Vastitas Borealis region of the Martian arctic onMay 25, 2008, where it spent the next five-plus months digging in the dirt tofind signs of water ice suspected to lay just below the surface.

?The $475-million mission, which outlasted its originalthree-month plan, confirmed the presence of that water ice and discovered manyother interesting characteristics of the arctic soil, including its unexpectedstickiness. Phoenix also observed frost forming on the dirt and rocks around itas Martian winter began to set in, as well as snow falling in the thin Martianatmosphere.

As winter set in towards the end of 2008 and the amount ofsunlight available to the lander decreased, Phoenix was able to do less andless. Mission managers finally lost touch with the lander in November 2008. Onthe slim change that Phoenix survived the winter with enough of its systemsintact to power up now that spring has returned to the landing site, the MarsOdyssey orbiter has been listening for signals from Phoenix, though none havebeen heard yet.

Mariner 9

When it reached Mars on Nov. 13, 1971, Mariner9 became the first spacecraft to orbit another planet, just edging out itsSoviet competitor, Mars 2.

Mariner 9 mapped 85 percent of the surface of the planet,revealing volcanoes (including the first detailed images of Olympus Mons, thelargest volcano in the solar system), huge canyons (including Valles Marineris,named for the spacecraft) and valleys that resembled dry riverbeds. A duststorm was raging when the probe first arrived at the planet, obscuring thesurface, but it eventually abated, allowing Mariner 9 to take the highestresolution pictures of the Martian surface up to that time. The spacecrafttransmitted more than 7,000 photos of the red planet back to Earth. It alsomade the first detection of water vapor on Mars, over the planet's south pole.The spacecraft remained in operation in its orbit until contact was lost onOct. 27, 1972.

The spacecraft was left in an orbit that would take 50 yearsto decay, after which it will enter Mars' atmosphere.

Mars 2 & 3

These identical Soviet missions each consisted of an orbiterand a lander were the first human-built craft to impact the Martian surface.

While the Mars 2 orbiter worked from the time it entered itsorbit in December 1971 until Aug. 22, 1972, the lander crashedon the surface and was lost. The orbiter's mission was to study the topographyand composition of the Martian surface, as well as the planet's atmosphere andmagnetic field. Mars 3's mission was also declared complete on Aug. 22, 1972,after its orbiter had made 20 orbits of the planet (Mars 2 had made 362) afterits orbital insertion on Dec. 2, 1971.

The Mars 3 lander made it to the surface of the planet, butcommunication stopped about 20 seconds after landing due to damage from thedust storm raging at the time. Both orbital probes sent back a total of 60images and returned data on the surface temperature, surface air pressure andwater vapor concentrations of the atmosphere of Mars.

Viking 1 & 2

Though the Soviet landers had made it to the surface first,Viking 1 was the first probe to land on the surface of Mars and perform itsmission when it touched down on Mars' Chryse Plain in July 1976. Viking 2followed on Sept. 3 landing on Utopia Plain on the opposite side of Mars.

Both missions included an orbiter and a lander. Viking 1 sentthe first color pictures of the Martian surface, which showed the red planet'srust-colored terrain and ruddy sky.

Both landers scooped up Martian dirt to analyze it forbiological signature, but found none, though some continue to debate thosefindings. The Vikingorbiters and landers transmitted over 50,000 photos of Mars and a treasuretrove of scientific data that is still being analyzed.

Mars Pathfinder & Sojourner

This lander/rover combo touched down at the Ares Vallisregion of Mars on July 4, 1997. The Sojournerrover and the Pathfinder base station spent several months analyzing theclimate, atmosphere, geology and surface composition of Mars.

The lander was formally named the Carl Sagan MemorialStation after it touched down on the red planet's surface. The rover/landerteam analyzed several nearby rocks, including some named "BarnacleBill" and "Yogi."? The mission, which found evidence that Marswas at one time warm and wet, was the first successful attempt at sending arover to Mars.

The lander outlived its anticipated lifetime by about threetimes, the rover by 12, returning thousands of images of the landing site. Thefinal data transmission from the robot team came on Sept. 27, 1997.

Mars Climate Orbiter

After traveling all the way to Mars, NASA's Mars ClimateOrbiter was lost on Sept. 23, 1999 when it shot within 35 miles (57 kilometers)of the Martian surface as controllers were attempting to put it into orbit. Theorbiter would have been torn apart in the planet's atmosphere.

The $125-million mission was to study Mars' weather andclimate, including the cycling of water and carbon dioxide. Investigations intothe orbiter's crash found that it occurred because of amix-up between the metric and imperial measurement systems that caused theorbiter to drift off course during its voyage and enter into a much lower orbitaround Mars than was planned.

Mars Polar Lander

The partner spacecraft to the Mars Climate Orbiter, the MarsPolar Lander met a similar fate to its sibling spacecraft 23 days after theorbiter was destroyed in the Martian atmosphere. The $125 million lander vanishedafter plunging into the Martian atmosphere on Dec. 3, 1999.

The Polar Lander was to conduct a 90-day mission at thesouth pole of Mars that would complement the Climate Orbiter's work inobserving the Martian climate and weather.

The polar lander was equipped with a robotic arm to dig updirt samples and instruments to analyze those samples. Subsequent orbiters sentto the red planet have attempted to photograph the surface near Mars' southpole where it is thought that the Polar Lander crash to see if they canidentify its remains.

Mars Global Surveyor

Launched toward Mars in 1996, the MarsGlobal Surveyor marked the first successful return to the red planet forNASA in two decades.

Originally slated for a full Martian year of observation(about two Earth years), the spacecraft out-performed its intended lifetime,lasting until 2006, when mission operators lost contact with the orbiter aftera routine adjustment of its solar array.

During its tenure, Mars Global Surveyor surveyed thelandscape of the red planet, watched the evolution of a dust storm on thesurface, and found evidence of gullies carved by water. The orbiter also actedas a communications relay for the Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit andOpportunity. The mission was officially ended in January 2007.

Of Mars and Machines

While fates of the Phoenix lander and others listed here arelikely sealed, NASA still has its resilient rover pair Spirit and Opportunityoperating on the Martian surface.

Opportunity is in good condition and has been making steadyprogress towards its next target, the distant Endurance Crater, making pitstops to investigate interesting rocks and other surface features along theway.

Spirit hasn't fared as well as its sister, becoming stuck ina Martian sand trap early last summer and being recommissioned as a mostlystationary spacecraft early this year. Scientists hope that Spirit won't yetjoin its fellow deceased spacecraft. Spirit has been put into a winter parkingspot, and mission managers are hoping it survives to continue its workobserving the interesting area it became mired in.

Along with the two rovers, NASA's Mars ReconnaissanceOrbiter and Mars Odyssey orbiter are still in good condition, taking images andobservations of the planet, including some of their fallen comrades.

These current denizens of Mars won't be the only spacecraftthere for much longer though, as NASA prepares to launch its Mars ScienceLaboratory (dubbed "Curiosity"), in 2011. Another mission, currentlystill in the planning phase, would bring samples of Martian dirt back to Earth.

- Images? Mars: A Spacecraft Graveyard

- Bestand Worst Mars Landings of All Time

- NASA'sGreatest Science Missions

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.