Clumpy Martian Soil Refuses to Budge

Efforts tojiggle a soil sample into one of the instruments on NASA's Phoenix Mars Landerwere unsuccessful, mission scientists said Monday.

Scientistsfirst attempted to deliverthe first sample of Martian soil to the Thermal and Evolved-Gas Analyzer(TEGA) Saturday. The instrument is designed to heat up soil samples in itseight tiny ovens and analyze the composition of the vapors that come off of it.

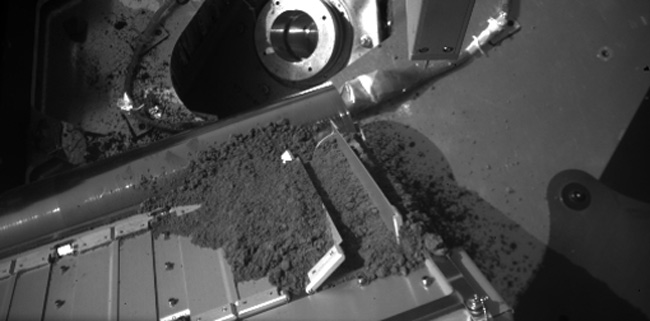

Thoughimages relayed back to Earth showed the dirt sittingon top of TEGA, detectors inside the instrument indicated that none of thesoil particles had fallen through the screen at the entrance to the oven.

"Whatwe found was that although we had an awful lot of dirt on that screen, almostnone of it made it down into the oven," said TEGA co-investigator WilliamBoynton, of the University of Arizona.

Missionscientists have said that the soil probably didn't make it through the screen,because it "appears to be quite cloddy," said mission science teammember Doug Ming, of the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The soilcould be clumping together for several reasons, including the presence of saltsthat bind the material together or moisture in the soil that developed duringlanding and cemented the particles together. "We aren't sure what'sactually causing this," Boynton said.

Mission controllers commanded the spacecraftto use the vibrator attached to TEGA to try to loosen the soil clumps and getthe sample into the oven. However, the first try only caused a few particles tofall in, not enough to take a measurement, though the soildid move.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Youcan see that the soil has actually moved, but it hasn't moved very far,"Boynton said.

Theclumpiness of the soil combined with the large amount of dirt delivered to theinstrument seems to be keeping the sample from getting in, which Boynton notedwas interesting because scientists were worried about having too little soil,not too much.

Scientistswill try once more to use the vibrator to get the sample into the oven, but"we're not too optimistic that that's going to be effective," Boyntonsaid.

Mission scientists have worked out anotheroption though, which they call "sprinkling."

Phoenix hasalready scooped up a second sample, and mission controllers will use this toconduct a "sprinkle test," first over the "dumping zone"next to the lander and then over the Microscopy, Electrochemistry andConductivity Analyzer (MECA) aboard the spacecraft. They will lower the scoopat the end of the robotic arm until it is almost level, then power up the arm'srasp (intended to scrap up samples of water ice) to vibrate the scoop andhopefully knock out the larger clumps of the Martian regolith. They will thentry to tip out a small portion of the sample onto MECA.

"Wereally are much better off with small amounts of soil," Boynton said.

If imagesshow that the sprinkle test was successful, controllers will have Phoenix dribble some of the sample into its optical microscope on Wednesday.

If thetechnique works for the microscope, they'll try it on TEGA. "If we dribbleit on slowly, we'll be able to vibrate it through the screen," Boyntonsaid.

Mission controllers were also able toconfirm that a springthey photographed on the ground of the landing site came from thespacecraft, specifically from a cable on the biobarrier, which protected therobotic arm on its 422-million mile (679-million km) journey from Earth toMars.

- Video: Sounds From Phoenix Mars Lander's Descent

- Video: NASA's Phoenix: Rising to the Red Planet

- New Images: Phoenix on Mars!

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.