Digital Temblors: Computer Model Successfully Forecasts Earthquake Sites

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

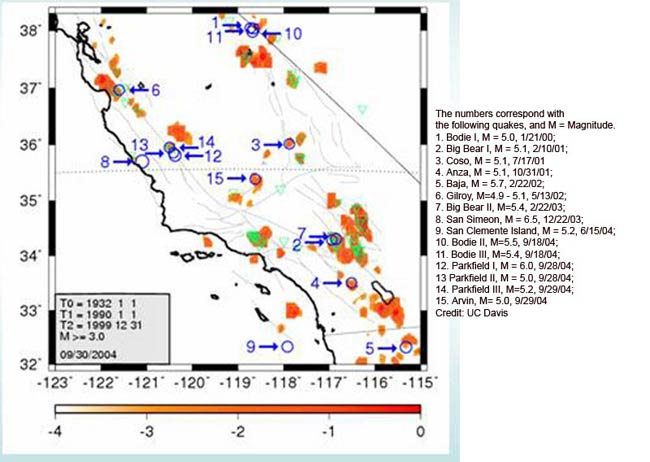

A Southern California earthquake forecast based on computer models has successfully pinpointed the location of nearly every major temblor to hit the region over the last four years.

Using historical seismic records as a base, the Rundle-Tiampo earthquake forecast has accurately predicted locations for 15 of the last 16 temblors with magnitudes greater than 5.0 on the Richter scale, all of which have occurred since January 2000. The forecast is currently about halfway through its 10-year timespan.

"I have to say that it's gratifying, though I'm not surprised," said Kristy Tiampo, an assistant professor with the University of Western Ontario in Canada, during a telephone interview. "The Southern California and Northern California seismic networks have quite good databases, the best freely available data around."

Tiampo worked with colleague John Rundle, director of Computational Science and Engineering initiative for the University of California, Davis to develop the quake forecast model. The forecast is one part of NASA's QuakeSim project aimed at developing new methods and tools for accurate earthquake predictions.

"What we're going for with [Rundle's] data is to make earthquake forecasting like doing weather maps," said Andrea Donnellan, QuakeSim principal investigator at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. "So that every year or month, you can update the map."

In addition to the Rundle-Tiampo forecast, the QuakeSim project relies on archived seismic data, extremely accurate global positioning measurements taken by space-bound satellites, as well as detailed interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) measurements to track surface changes.

"It's mostly a mystery," Donnellan told SPACE.com of the Earth's seismic activity. "One of the things we're learning is that you can't study one fault...each earthquake at one fault affects others."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Building a temblor forecast

With funding from NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy, Rundle and Tiampo pored through Southern California seismic records from 1932 onward, inserting the data into a computer model designed to seek out tremor hotspots within the state.

"The computer model simulates the Southern California [seismic] network," Tiampo said, adding that in addition to using earthquake data, the forecast also incorporated modeling techniques typically used for neural net and turbulence simulations.

The Rundle-Tiampo forecast split the southern half of California - from San Francisco down to the Mexican border - into about 4,000 individual boxes and calculated the seismic potential for a strong earthquake in each space between 2000 and 2009. Released in 2002, the forecast has apparently pinned the location of 11 earthquakes, while four others occurred within the two previous years.

The outstanding earthquake, a 5.2magnitude temblor that shook a region covered by the Pacific Ocean near San Clemente Island, occurred on June 15, 2004. Rundle has said the forecast may have missed the shaker because it was centered on a region near the edge of the state's seismic network. That may have added an increased uncertainty to its location, he added.

"What I think these hotspots should really be used for is education...to make sure that gas lines are up to code in these regions and acquire the resources to prepare buildings for quakes," Tiampo said, adding that there are still just over five years left to measure the forecast's effectiveness. "And I would also like to see the model revised in upcoming years."

Estimating the magnitudes - in addition to the location - of potential tremors and narrowing the forecast timeline are prime targets for improvements, researchers said.

"You would want to be able to give a probability, such as between the next six months and two years, for a possible earthquake," Tiampo added. "And then keep a running forecast going as the system changes."

Spotting Earth strain from the orbit

Both Tiampo and Donnellan agree that while the Rundle-Tiampo forecast appears to be on the right track, it is restricted solely to seismometer records. The model does not include data on the slow deformation to the Earth's surface that can occur without registering on the Richter scale.

"Seismometers only measure the shaking action," Donnellan said, adding that earthquake researchers have observed high strain within the hotspots targeted by the Rundle-Tiampo forecast.

That strain can slowly shift the Earth's crust. For example, after the 1994 Northridge earthquake, which registered 6.7 in magnitude, the surrounding mountains continued to move, growing a full 12 inches (30 centimeters) taller, Donnellan said.

Donnellan said QuakeSim researchers have demonstrated that InSAR measurements could detect high strain events from space, but only by borrowing time with spacecraft that were not designed specifically for the task.

A dedicated space instrument would not only add to the baseline of earthquake data, but also reach temblor prone regions like Turkey where large-scale seismic measurements are unavailable, or Japan, where seismic network changes has made consistent long-term measurements difficult to obtain, she added.

During an October 2004 workshop in Oxnard, California, researchers gathered together to determine the requirements necessary for a dedicated InSAR space mission.

"With a five-year mission, you could pretty much map the surface strain on the entire globe," Donnellan said, adding that such an instrument could also serve as a worldwide earthquake watchdog. "Anything above a 5.0 you should be able to detect, which could be about 200 earthquakes a year."

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.