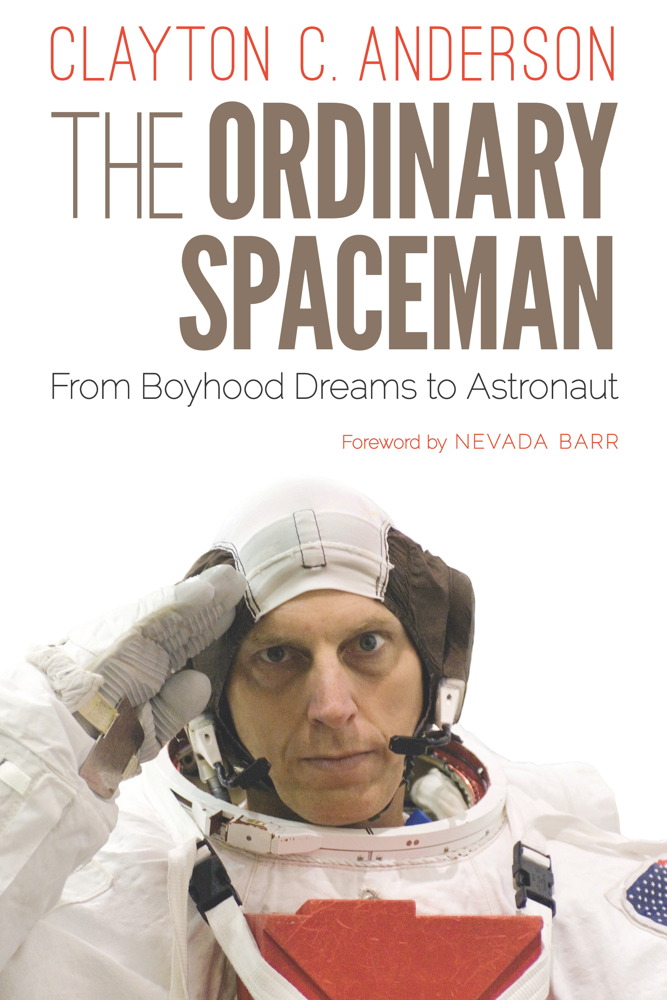

'The Ordinary Spaceman: From Boyhood Dreams to Astronaut' (2015): Book Excerpt

Clayton C. Anderson is intimately familiar with how to become a NASA astronaut: After all, he applied 15 separate times before he was accepted into the program.

Luckily, one of them stuck — and in his new memoir, "The Ordinary Spaceman: From Boyhood Dreams to Astronaut" (University of Nebraska Press, 2015), Anderson traces his path through NASA and astronaut training as well as his experiences as an astronaut both in space and on the ground. Anderson flew to space twice, a 5-month mission on the International Space Station in 2007 and a shuttle mission in 2010, and both times he brought his unique brand of ingenuity and humor to his astronaut duties.

Anderson doesn't shy away from describing both the highs and lows of his 30-year NASA career: The excitement and fun of learning as a "baby" astronaut, the joy and challenge of working with an elite team and training in Russia, frustration with bureaucratic inefficiencies, and the harrowing experience of being an escort to the astronauts' families during the Columbia disaster. (Read a Q&A with the author here. )

In this excerpt, from the beginning of the book, Anderson describes what he calls his first real astronaut experience — a hair-raising supersonic ride in a T-38 jet:

Chapter One of "The Ordinary Spaceman"

Life is filled with firsts: first word, first step, first date, first kiss, first tax audit . . . well, you get the picture. The life of a brand-new astronaut is filled with firsts as well. From the day you report to the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston and journey up the six flights of stairs in Building 4 South to the hallowed halls of the Astronaut Corps, you are destined for experiences that, while fully expected, are certainly not inconsequential: your first staff meeting, first trip to the men's restroom, first run-in with a veteran astronaut who thinks you might be taking over his next spacewalk. All are a part of the rite of passage so crucial to becoming an accepted member of perhaps the most elite group of men and women on (and off) the planet.

Perhaps the most significant of these firsts should also be defined as a perk . . . a perk that occurs at over 850 miles an hour! The day was November 4, 1998, only two short months after I had reported for duty as an astronaut candidate (ASCAN) at JSC. The weather was bright and sunny with the temperature in the low eighties: a beautiful fall day in southeast Texas, the time of year Texans long for and then lament when it passes quickly and the first of December arrives.

I had arrived at Ellington Field plenty early, with a healthy amount of nervous anxiety. A former air force base in southeast Houston, Ellington Field has been repurposed as the home to NASA's fleet of T-38 training jets. I was anticipating an experience that would stick in my memory forever. I tentatively climbed the narrow internal stairwell on the southeast side of Hangar 276 while casting longing, worshipful glances at the beautifully sleek white-and-blue jet aircraft on the floor below. Within this massive building all the jets rested quietly and majestically, each an individual piece of a well-designed jigsaw puzzle nested together so the entire fleet could avoid exposure to the brutal windstorms, rain, hail, and searing heat of south Texas. Feeling every bit the rookie in this unfamiliar place, I carefully opened the blue door to the "ready room" — the sacred area where pilots and astronauts execute their individual flight preparations. Inside, I quickly made my way toward the far hallway, silently hoping that I wouldn't be stopped and questioned.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

My presence was announced with each creaking step, as the floor of the World War II–era hangar squealed in distress under the pressure of my highly polished black leather military boots. I searched for the office adorned with the right nameplate. A third of the way down the hall I found myself at the door of Col. Andy Roberts (U.S. Air Force, Reserve), whose title was astronaut instructor pilot (IP). I was here for a baptism of sorts, to fly for the first time in one of NASA's T-38s. (The T-38s — "T" for "trainer" — are a fleet of twin-engine jets maintained by NASA specifically for astronauts to fly.)

Wearing my new royal blue astronaut flight suit, complete with a nametag declaring that Clayton C. Anderson, JSC, had made it this far, I stood as tall as I could while I waited patiently for Andy's acknowledgment that it was okay to enter the room. Beckoned with a warm smile and a welcoming wave, I entered, then paused for a moment to survey the lair of the former U.S. Air Force fighter pilot.

Andy's workspace was shared with three other IPs and adorned with the unceremonious trappings one might expect at a U.S. government facility. The drab gray government-issue office furniture and cubicles were arranged as if to barricade themselves from the outside world and anyone or anything that might ruin their day. Bookshelves and file cabinets were set up the way kids might build forts in their grandma's front room. As my eyes scanned this cacophony of paper and personal mementos, gathered through years of career service and family milestones, I noticed that my treasured rookie flight suit — so crisp, blue, and stiff — now felt like a rough piece of cardboard freshly removed from a three-pack of new t-shirts. Nerves and anxiety alerted every pore, causing me to break into a nice preflight sweat, as I realized how well worn my veteran-fighter-pilot-turned-instructor's garb was compared to mine.

His flight suit, once the same brilliant hue and crispness of the one I so proudly wore, had the look of a comfortable denim shirt, soft to the touch and conforming to each contour in the wearer's upper torso. The one-time bright royal blue had become a faded blue pastel, reminding me a bit of a favorite old bathrobe. Yet his appearance was one of total confidence. On each of his sleeves, near his biceps, were the classic military-type patches — a U.S. flag on the left and the circular flight instructor patch of the NASA Aircraft Operations Directorate on the right. Even these patches had faded, beaten down by hours upon hours of the relentless sun shining through the clear glass cockpit of the T-38, testifying to flight hours so numerous that they require a computer to track. Each thread had been hammered by ultraviolet radiation, every flight pushing the fabric further toward the yellow end of the spectrum.

My flight instructor's suit was repeatedly an inanimate passenger in a jet as it ascends through the atmosphere to pierce cottonlike clouds the way a needle drives through a piece of fabric. Yet for all the abuse that suit got, its ultimate reward was to be touched by beams of high-energy radiation emanating at the speed of light from our very own star, poised majestically ninety-three million miles away at the center of our solar system.

I looked at Andy's nametag framing his name and rank. Though tarnished from wear, the time-honored air force silver border still shone proudly as the emblem of the service for which he risked his life. Oh sure, he could have gotten a new flight suit — all it took was a short walk across the hangar floor and up another flight of stairs to reach the equipment shop. He could have been wearing one just as stiff and uncomfortable as mine. But as I would quickly come to learn, he wore his "gently used" flight suit with as much honor as any of the others who have so proudly served; he wore it to commemorate how he had bravely challenged the skies for his country and had come out a winner every single time.

Andy was on the phone finishing a call with his wife. I was not eavesdropping, but just before he hung up I heard him say something like, "Honey, I've got to go. I've got one of the new ASCANs here for his 'Zoom and Boom' ride." I was already nervous enough, and hearing those words certainly got my attention. I feared that I would quickly be coming to grips with the real meaning of the phrase "baptism under fire."

I knew Andy from one of our previous T-38 training lectures when he had described to our class the nuances of the T-38's hydraulic system. We reintroduced ourselves, and after five minutes of chatting about life in general, he stopped the small talk. His tone of voice changed to that of an air force pilot, and he started to pepper me with technical details relating to our upcoming "sortie." This training flight would take place in the area designated as w-147c (or whiskey one-four-seven charlie). W-147c, a practice area covering the northern Gulf of Mexico, was artistically depicted on our flight control avionics screen as a huge triangle of bright green. Our preflight briefing covered each and every detail, from the tail number of our jet to the high-threat areas we would encounter along the way (birds near the runway, small planes in the area of Ellington Field), as well as the visual signals we would use to communicate with each other in the event of an emergency and possible ejection from the aircraft. When we came to the subject of communication and the situation known as "nordo" (no radio), Andy calmly asked, "Do you think you can operate the radio system, Clay?"

"Yes, sir, I believe I can," was my confident reply. Every ASCAN new to flying receives classroom ground school training in all aspects of the T-38 and its systems, including communication and the radios. With that, Andy handed me a small sheet of paper complete with the list of frequencies we would need for our one-hour-and-fifteen-minute flight—a flight that would fully (and finally) expose me to the high-speed world of jet aircraft.

After a quick bathroom break we reconnoitered in the parachute room, where more than one hundred green military parachutes hung from symmetrical racks of simple wooden poles, having been prepared meticulously by the aircrew equipment staff. There they waited for the next astronaut or pilot to slide into one, cinch the straps tightly, and silently pray that it wouldn't be needed that day. Andy and I each chose a parachute matching our size (extra large for me), threw it over our right shoulder, grabbed our helmet bags from our designated cubbies, and headed to the flight line.

As we strode to the jet, I held myself tall and proud. Inside, my nerves tingled with anticipation. After quickly stuffing foam earplugs into my ears, I solemnly followed Andy around the aircraft, watching with rapt attention as he performed and narrated a detailed preflight check of the jet and her high-tech appendages.

As our "bird" was in the expected pristine condition, I climbed the blue ladder that hung from the sill of the rear cockpit and settled into the back seat of this vintage two-seater. As I wasn't accustomed to the process of sitting down and strapping in, a longtime member of the flight line crew helped me jostle into all of my flight gear: gloves, helmet, pub bag (as in "publications" — maps and charts), then verified that I had gotten the myriad of connections, buckles, and straps in the proper configuration for a safe trip. With a pat on my shoulder and a smile that more closely resembled a smirk, he looked me straight in the eye and bid me a safe flight. I got the distinct impression that he was well aware of my rookie status.

Moving with what I thought was the speed of a tortoise wallowing in molasses, I checked my rear cockpit gauges, dials, and displays to make sure they resembled the configuration I had been taught to expect for takeoff. Strapped tightly into my seat, with my helmet's chin strap locked in place, I cast my eyes to the lower center of the cockpit, just slightly above the control stick, to double-check the radio management system display. Comparing the five LED segments to those on the handwritten card that was clipped to my kneeboard, I relaxed just a bit, confident that I had entered the correct numbers into the various frequency slots.

Andy's voice was cool and calm: "Ready to start on the right." He pushed the corresponding start button located in his front cockpit. Then, watching to see that the RPM gauge reached the required level of 12 to 14 percent, he called out, "Start the clock," verbally acknowledging that the ignition circuit would be armed for only thirty seconds. As he began to gently ease the right engine throttle forward, the quiet inside the cockpit was instantly filled with the powerful roar of a jet turbine. With the engine spinning at more than 2,000 RPMS and drinking fuel by the second, the variable-area nozzle was now spitting out the hot pungent exhaust of Jet A fuel. A massive thirty-six hundred pounds of thrust are produced at sea level by this General Electric–built, eight-stage turbo jet engine. Andy repeated the process for the left engine. My earplugs were already paying huge dividends as the thunder of the two axial-flow engines hummed in near-simultaneous rhythm.

With an easygoing style born of years of military jet experience, Andy contacted the control tower for clearance: "Ellington Tower, this is NASA niner-one-seven, I-F-R to whiskey one-four-seven charlie, clearance on request."

After a wait of ten to fifteen seconds, the tower operator at Ellington keyed his microphone and sent his voice crackling across the airwaves: "NASA niner-one-seven, cleared to whiskey one-four-seven charlie, radar vectors, then via EFD radial two-zero-six at fifty. Call ready for taxi."

Not really understanding all of what the tower operator had just said, I was frantically trying to manipulate my ballpoint pen. My ability to legibly "copy clearance" in this foreign language was severely compromised by the Nomex flight gloves covering my shaking hands. Plus, I had to capture this critical information on a sheet of paper strapped to a kneeboard wrapped tightly around my right thigh. Frustrated and overwhelmed, I gave up. My pilot provided me with a second chance by calmly repeating the clearance exactly as it was dictated by the tower: "Ellington Tower, NASA niner-one-seven, cleared to whiskey one-four-seven charlie via radar vectors to EFD radial two-zero-six at fifty. We are ready for taxi and we have 'echo.'"

"NASA niner-one-seven, Ellington Tower. Taxi to runway oneseven right, via hotel," said the faceless voice in the tower.

In the front cockpit, Andy simultaneously pushed the engine throttles slowly forward with his gloved left hand. The jet patiently roared to life, inching forward from its parking spot on the tarmac, as we initiated the long trip from the T-38 hangar on the field's south end, down the intersecting taxiway "hotel," to runway one-seven right at the north end of Ellington Field almost eleven thousand feet away.

The taxi to runway one-seven right, at the far end of the vast expanse of concrete, takes slightly longer than to the neighboring strips. This was a good thing for me. It gave me ample time to do the necessary pretakeoff checks and to get one last briefing on what I was to watch for as we barreled down the runway.

Even early in November the Texas winds come predominantly from the south. Using runway one-seven right—taking off into the wind—gives a nice added lift for the T-38's short stubby wings. Another call to the tower from Andy, letting them know we were ready for takeoff, resulted in a standard call-back phrase from our Ellington Field air traffic controller (ATC): "NASA niner-one-seven, turn left heading zero-niner-zero [090], maintain two thousand [feet altitude], cleared for takeoff, runway one-seven right." Andy repeated the call back to the tower, then smoothly muscled the two side-by-side thrust levers forward, gently pushing our twelve-thousand-pound aircraft onto the runway. With his toes pushing hard and forward against the jet's brake pedals, he drove the throttle quadrant levers all the way to their initial stops, the position known as "military power." The engines, producing near the thrust level required for takeoff, were trying to drive the jet down the runway. Andy's strong legs on the brakes were the only force keeping us stationary. "Clay, you ready to go?" Andy asked.

My meek "yes" surely must have sounded to him like a timid little third grader.

Andy pulled his feet back from the brake pedals and tightened his grip on the throttles. He added just enough force to push the handles through the detent and then slammed them full forward past the military stops into the afterburner position. With the engines whining at their highest thrust level, the jet leaped forward down the runway with the horsepower of more than twentyfive thousand metallic stallions.

The thrust force increased against my chest as the needle on the rear cockpit speedometer began a steady crawl clockwise. (Its original at-rest position is 60 knots.) Andy, appearing to be in total control (remember, I only knew how to work the radio), made the requisite calls that would one day emanate from my vocal chords: "Off the peg—60 knots, 100 hundred knots, go speed." The scenery outside began to blur.

"SETOS [single engine takeoff speed, pronounced SEE-tose]. SETOS plus ten," came the call that indicated we were now traveling just fast enough to take off even if we were to lose one of our engines.

We were flying down the runway at a velocity of over 155 knots, a speed that I had never before experienced. Using his feet on the rudder pedals like a surfer riding a surfboard, Andy held the jet's nose directly on the runway's center line. A slight backward pull on the control stick lifted the nose just five degrees and we were airborne. Buildings on the ground rapidly began to resemble little dollhouses.

Andy called me on the intercom frequency. With an impish tone in his voice that undoubtedly matched a face I couldn't see, he suggested I take a look out the window and tell him what I saw. "The Johnson Space Center and Clear Lake City," was my reply.

Laughing, Andy said: "Look again."

Not knowing what he was trying to get me to say, I once again scanned the shrinking scene below in a vain effort to find the clue to this game we apparently were playing.

I choked out another ill-fated reply: "Uh . . . NASA?"

He laughed a second time, then told me to check the angle of flight. A scant minute since clearing the ground and we were screaming into the sky in a position that almost approached vertical!

When we reached our destination — 41,000 feet in altitude, high above the Gulf of Mexico — I was calmed by the fact that we had slowed to a more leisurely rate of speed, with a correspondingly lower angle of climb (the angle that the jet's nose makes with the horizon). I began to engage Andy in light chatter as if I were a veteran of high-speed aircraft. But this brief period of confidence began to erode when Andy asked a very strange question.

"Clay, can you hear me?" was the call from the front cockpit. "Yes, I can hear you," I answered without reservation.

"Clay, can you hear me?" came back again through my helmet's headset, causing me to think that maybe I needed to speak louder. "Yes!" I nearly bellowed into my oxygen mask, beginning to grasp the fact that perhaps something important was going on.

In the next second the jet began to rock violently. Something had gone terribly wrong. My dearth of experience was becoming more apparent with every passing second. Forcing myself to stay calm, I began racking my brain to recall any portion of my miniscule training. Almost as if by accident, an idea started to kick in. I glanced to the forward cockpit and watched the back of Andy's head, steady in front of the thick scratched glass.

Apparently our communication system was malfunctioning. I tapped my right ear with my royal blue gloved hand, then followed with the universally understood thumbs-up signal where Andy could see it in the rearview mirror mounted above the right side of his instrument panel. Next, with renewed hope that I had actually figured out what was going on, I tapped my oxygen mask, then motioned thumbs-down to indicate that perhaps I could hear him but he couldn't hear me.

His calm reply over the limping intercom put my fears at ease. "Looks like the intercom is intermittent. We're gonna have to head for home," he said. A second thumbs-up from me and we turned back for Ellington. My thoughts turned from dealing with a brewing disaster to "Oh my God, what did I do wrong?!"

We pulled back into the chocks at the line and completed the shutdown checklist. As we raised our cockpit canopies, I heard the flight line lead, Bob Mullen, ask Andy the question that all rookie astronauts fear: "What did he screw up?"

I was too new at this to have known I should begin the flight with the famous "astronaut prayer": "Dear Lord, please don't let me f*** this up!"

As I had done during our taxi to the hangar, I once again checked and rechecked every connection and pushbutton in that cockpit that I could find. Still not seeing anything out of order, I grew more and more confident that I had set up the radio panel correctly and that my helmet and communication connections had been made without error. Then the jet technician appeared, moving one of the blue metal ladders into place and climbing up slowly to my level. He cast a careful eye over the switches and dials of the rear cockpit. His skilled eyes and hands checked the exact same pushbuttons and connections that I had evaluated multiple times.

His resulting conclusion, that the radio management system (RMS) box had failed, vindicated me. A wave of relief allowed a huge sigh to push forth from my lungs. Without missing a beat, and without us even having to climb down from the jet, a new RMS box was swapped with the faulty culprit.

Back on the runway, we were once again screaming for the sky. This time the trip out to the Gulf was uneventful, except for the fact that Andy asked the ATC for a "block altitude" from twenty-eight thousand to forty-one thousand feet. When the ATC responded affirmatively, Andy asked if I would like to break the sound barrier. Thinking "Hell, yes!" I responded "Sure." In my mind I pictured us flying straight and level, screaming through the sky high above the water. I couldn't have been more wrong.

After we finally reached our target altitude of forty-one thousand feet, Andy easily leveled the T-38 until the digital readout from the altimeter began to steady itself, displaying forty-one followed by three zeroes. Within seconds, Andy rolled the aircraft upside down while pulling the stick back as far as he could, sending the jet's sleek nose pointing to the Gulf of Mexico. He continued to pull back until the stick nearly contacted the front edge of his seat. The plane seemed to flip over backward and plunge straight down toward Earth!

Flipped over on our backs, as if we were performing a halfgainer from the diving board of the community swimming pool, we sped directly for the white-capped waves below — which were growing larger with each passing second. "Check our velocity," Andy called to me as he gave the jet another half-rotation to place us rightside up again.

My head still spinning from my first backflip in a supersonic jet, I zeroed in on the velocity indicator (called a tape) and struggled to focus on it. Velocity: 0.88, 0.90, 0.92. I watched the numbers climb steadily, its pace dictated by the constant pull of Earth's gravity, coupled with the drive from two spinning eight-stage turbo jet engines. The numbers passed the digital value of Mach 1.0. We were traveling at the speed of sound!

Like a Tour de France biker fighting to reach the top of the highest hill, the numbers climbed slowly while the rate of increase started to level off. Finally, the value stayed steady at 1.27. We were now traveling faster than the speed of sound!

My newbie astronaut brain told me that I should be hearing a sonic boom. Seconds later, the only sound I heard was a voice inside my head saying "Duh!" We were causing the sonic boom. We were moving so fast that there was no way we would be able to hear it. The sonic boom was already far behind us.

The culmination of my first time breaking the sound barrier was as unexpected as its initiation. As we neared the bottom of our block altitude at twenty-eight thousand feet, once again subsonic on the normal side of the invisible barrier, Andy pulled back hard on the stick again and arrested our plummet toward terra firma. The resulting pullout felt like the jet's steel frame was bending, resisting that force of physics Newton discovered when an apple fell on his head. My weight of 195 pounds doubled in an instant and I sank deeper into my rear cockpit seat, feeling the pull from the force of Earth's gravity on my backside.

Falling back on memories of the Tom Cruise movie Top Gun, I began to make loud, serious grunting noises from the rear cockpit, with teeth clenched, pushing hard against my abdominal muscles as if engaged in a timely bowel movement. This vain attempt to force blood back to my head was only minimally successful. My peripheral vision began to go black like curtains being closed on a stage.

With renewed vigor and forceful abdominal thrusting brought on by my sudden fear of going blind and passing out, my vision eventually returned to normal. I was beginning to relish the excitement of this awesome experience when a guttural chuckle came through the jet's intercom system. Then Andy said, "You don't have to make so much noise when you're doing that." My pilot had been listening to my efforts. This pulled me out of my fighter pilot vision and returned me to the reality of a rookie flying his first flight.

Humming through the sky on a straight and level trajectory, doing about 350 knots, Andy suggested that I try an aileron roll. "You bet," I said. "What do I do?"

Andy's quick reply was, "You just have to push the stick to the right and hold it there for a few seconds. Let the jet roll, then bring the stick back to its normal position."

It sounded simple enough, so I gave it a try. I moved hard right on the stick, and held it for all I was worth. When the timing felt right (how would I know?), I slammed the stick back into the neutral position and looked up through the clear glass cockpit expecting the cloudless blue sky I had been enjoying since take-off. Water was all that I could see. We were upside down! Andy was laughing again. Assuming the role of instructor, he suggested that I "roll it just a bit further." A quick movement of the stick to a hard stop on the right, and then a return to its vertical neutral position, produced a glorious vision of blue sky over my head that made me right with the world again.

During our T-38 ground school training, we had been warned many times about the phenomenon known as the dreaded "stomach awareness." You are probably quite familiar with it—that feeling you get on a roller coaster ride for the third time, after having just downed a deluxe bacon cheeseburger and fries with a chocolate shake. Where you break into a cold sweat and your stomach starts to remind you that, yes, it's still there. Perhaps you pop a peppermint to help alleviate the cotton mouth that has taken over your tongue. Well, our next maneuver, the loop to loop, brought it all to the forefront of my consciousness.

Andy's plan was that he would first demonstrate this maneuver, which began with another hard pull full aft on the control stick, and then give me a chance to show if I'd been paying close attention. For the second time in our sortie we flipped over on our back, with the nose of the jet eventually pointing downward. But this time we continued through the bottom of the loop, and my body was subjected to another serious episode from the pull of gravity. Now a full-fledged veteran of these physiological effects, I was confident that this time would not present much of a challenge. It wasn't until sweat began to pour from the top of my head down the front of my face—it felt like a rain shower gushing down inside my visor — and my vision started to go black again that I understood I didn't really have any idea how to combat what was going on. I resumed my intercom-audible grunting and groaning, prompting an additional hearty laugh from my partner in the front cockpit. Embarrassed again (this was becoming too routine), I pressed on, undaunted. Desperately hoping for regained vision, I pushed so hard against my abdomen that this time I thought I was going to need a diaper. It was apparent that stomach awareness training — part 2 — had kicked in. I extended my Nomex-gloved right hand toward the oxygen system controls.

I pushed the 100 percent oxygen (O2) and emergency levers hard forward to "gang load" the regulator, just as I had been taught in training class. Then I raised my helmet visor and rotated the air conditioning vent to blow frigid air directly on my face. It was helping, but the second loop was already in progress. While my heart wanted to stay aloft, my vestibular system was telling me that if we didn't land pretty soon, I was going to have a nasty mess riding with me in the cockpit.

The pullout of loop 2 brought Andy's glance to the depleting fuel gauges and resulted in his call that we needed to "RTB [return to base] to Ellington." While my glance could extend not much farther than the end of my nose, I thought that I had died and gone to heaven. Only a few more minutes for me to hang on until landing at NASA OPS and I would have achieved a critical milestone from among my many astronaut goals: not to puke on my first T-38 flight.

"Driving" the jet back to Ellington Field meant we were in a continual descent from about thirty-five thousand feet. The more we descended the hotter the inside of the aircraft became, since the jet's air conditioning system functions much better at higher altitudes (where the air is already cold and thus easier to keep that way). I was getting uncomfortably warm and beginning to sweat all over again. In perfect neurovestibular fashion, the warmer I got, the queasier my stomach became. Out of habit, I continually checked the oxygen and ac levels just to make sure it was still in position as "100%" and "Emergency" (full fan). Unfortunately, each time ended with the realization that nothing had changed, and it wasn't going to get any better until we were able to pop open the canopies and climb back down to the ground.

All was silent in the jet for the final uneventful minutes, each of us preoccupied with our own thoughts. Andy's could have been about heading home to his family or teeing up for eighteen holes of golf. Mine were focused on keeping all vomit contained within. Until we pulled to a stop on the tarmac adjacent to the NASA hangar, I was fighting with everything I had to keep it down.

With a final firm push on the brake pedals, a run through the shutdown checklist, and a nod from the flight line personnel, Andy punched off the engines and unstrapped himself from his seat harness—almost simultaneously, it seemed. I fumbled with my connections and gathered up all my gear while Andy hopped from his seat to the ladder and gave me what I figured was his obligatory "attaboy"—telling me how well I had done and that he had to bolt to his youngest son's soccer game.

Offering a sincere thanks to Andy and a not nearly so sincere shout of "I really enjoyed it," I was left to my own devices. I walked slowly from the jet back to the chute room. As I hung up my parachute and placed my helmet bag back into my cubby, the thought occurred to me that for the first time in my life, I had cheated death during a jaunt at jet speed!

I entered the locker room and sat down in front of my locker. I was not feeling too chipper. The combination of nausea and temperature was doing a number on me. I decided maybe a cold shower would be the ticket to recovery. After about twenty minutes of cold water pulsating and pouring down my exhausted body, which leaned ever so gently against the side of the fiberglass shower stall, I felt rejuvenated enough to return to my locker. Striking a pose like Rodin's Thinker, including being stark naked as I sat on the bench, I mustered enough energy to begin to slowly put my clothes back on. Once fully dressed, and with a few minutes of rest under my belt, I was feeling pretty good . . . and a little cocky. I was ready to face the world again, no longer a rookie with zero flight time!

Weaving through the two sets of double doors that led to the open hangar, I stood again on the hangar floor where this flying adventure had begun a few short hours ago. Admiring the sleek beauty of these fantastic airplanes, standing mere inches apart on the shiny gray floor, I took in the sounds . . . there were none (it was past quitting time) . . . and the smells . . . there were plenty, ranging from jet fuel to that familiar smell of new rubber tires.

Turning my head to verify there were no obstacles in my path to the exit door at the hangar's north end, I saw a quiet sentinel, its identity revealed by the label "trash" stenciled on the metal lid. I am not exactly sure what happened in that next instant, but I think it was the power of suggestion taking over deep within my cerebral cortex. A force welled up and instructed me to remove the trash can lid, thereby allowing the entire contents of my stomach to fly out at roughly the speed of our T-38 takeoff some minutes before.

Yep, it is true. As much as I hate to admit it, this steely-eyed astronaut's first "Zoom and Boom" had become nothing more than a "Whirl and Hurl."

BUY "The Ordinary Spaceman: From Boyhood Dreams to Astronaut" >>

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.