How NASA's Artemis moon landing with astronauts works

NASA wants to go back to the moon. Here's the plan.

1) NASA's new moon-landing leap

NASA plans to place astronauts on the moon again sometime in the 2020s through an initiative dubbed the Artemis program. The Artemis program will see the first woman and the first person of color land on the moon, along with the first lunar participation by international astronauts. The infrastructure for the program is vast, ranging from a space station outpost to spacesuits, and from launching and landing equipment to commercial payloads. The following slides show the bigger elements of Artemis, along with the program's history and where it will go next.

2) Artemis program history and 2024 goal

NASA's Artemis program was formulated under the administration led by President Donald Trump and is continuing under President Joe Biden. The first strong hint of a moon mandate came in Trump's Space Policy Directive 1 of December 2017, which told NASA to focus on lunar missions. Then, in March 2019, Vice President Mike Pence — citing a "space race" with Russia and China — set an ambitious deadline for NASA to land humans near the moon's south pole by 2024, at least four years ahead of the agency's schedule at the time.

The 2024 deadline was met with some criticism and concern almost immediately, with questions arising from within NASA, Congress and other institutions about how the agency would prepare new elements — such as a rocket, a spacesuit and a human landing system — safely in time. The NASA administrator at the time, Jim Bridenstine, was adamant safety would be respected. Meanwhile, Congress did not allocate as much money for elements of Artemis as the Trump administration had requested. By August 2021, delays to spacesuit development made a 2024 deadline "not feasible," NASA's inspector general found.

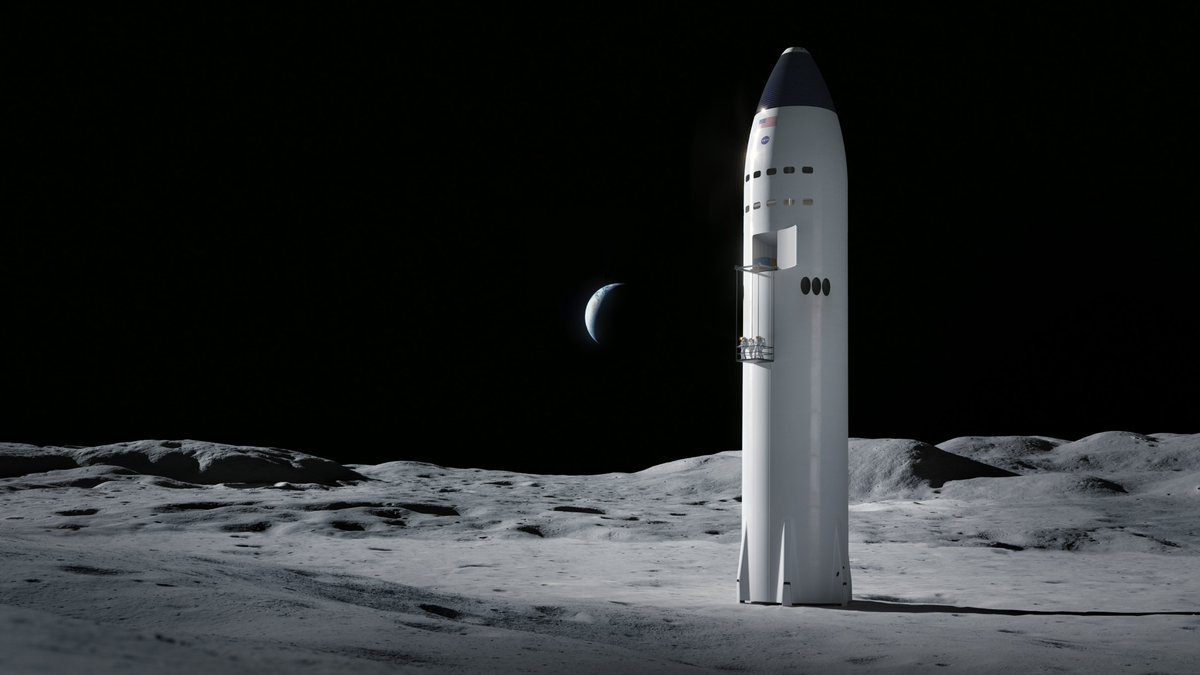

3) Human Landing System

In April 2021, NASA selected SpaceX as the sole-source provider for Artemis' human landing system. The $2.9 billion contract means the agency will use SpaceX's Starship system to land humans on the moon. But implementation of the contract has barely begun after two delays, first by official protests by competitors Blue Origin and Dynetics (overturned by the Government Accountability Office in August 2021) and subsequently by an ongoing lawsuit from Blue Origin. The stand-down is expected to go to at least Nov. 1, 2021.

Starship is the prototype system SpaceX is developing for human deep-space missions. It has gone through many iterations in recent years. On Aug. 6, 2021, Starship SN20 (Serial No. 20) was stacked aboard its Super Heavy rocket for the first time, making the system the tallest ever in the world. It stands 395 feet tall (120 meters), taller than NASA's massive Saturn V moon rocket, which was 363 feet tall (110 m). The Starship HLS version is still under development, but multiple media reports suggest the landing spacecraft will not have a heat shield as the moon has no substantial atmosphere.

4) Space Launch System rocket

NASA's Space Launch System is the agency's heavy-lift rocket designed to bring humans and cargo deep into the solar system. It was first announced in September 2011 under the administration of President Barack Obama, back when NASA was targeting "flexible destinations," including Mars and a near-Earth asteroid, for future human missions. After overcoming delays and development challenges in late 2020 and early 2021, SLS is currently slated to make its debut flight, Artemis 1, in December 2021 when it will launch an Orion spacecraft on a loop around the moon.

SLS will be available in a few configurations, with the astronaut-launching lunar version anticipated at 321 feet (98 m) tall. It is being developed in three major phases with different capabilities, mostly in the upper stages: Block 1, Block 1B, and Block 2. The core stage of all versions will be built by Boeing, which received an initial $2.8 billion contract for the work in 2014. The core stage includes four liquid-propellant engines — using RS-25 engines, also used on the space shuttle — and two solid rocket-boosters to heft the rocket into space.

5) Orion spacecraft

The Orion spacecraft's development history long predates Artemis. NASA selected Lockheed Martin to build the gumdrop-shaped vehicle in 2006 under a contract then valued at up to $8.15 billion. Initially Orion was designed for the President George W. Bush administration's Constellation program to bring humans to the moon and Mars; the program was canceled under Obama in 2010. Orion was revived with a modified system design in 2011, with NASA saying the design could be adapted for the newer exploration vision for flexible destinations. Orion was then kept as the spacecraft of choice for Artemis.

Orion has successfully performed one flight test to date, a high Earth-orbiting mission called Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) on Dec. 5, 2014. Development delays to SLS have pushed back an expected second flight for the capsule several times since 2017. Orion's next expected flight, Artemis 1 in late 2021, is expected to see Orion go around the moon carrying experiments, cubesats and human test articles to examine the stresses of spaceflight on future astronauts. Orion is 16.5 feet (5 m) in diameter and can carry four astronauts, NASA says. Like its predecessor, the Apollo command module, Orion will include a crew module and a service module with vital spacecraft systems for power, fuel and oxygen generation.

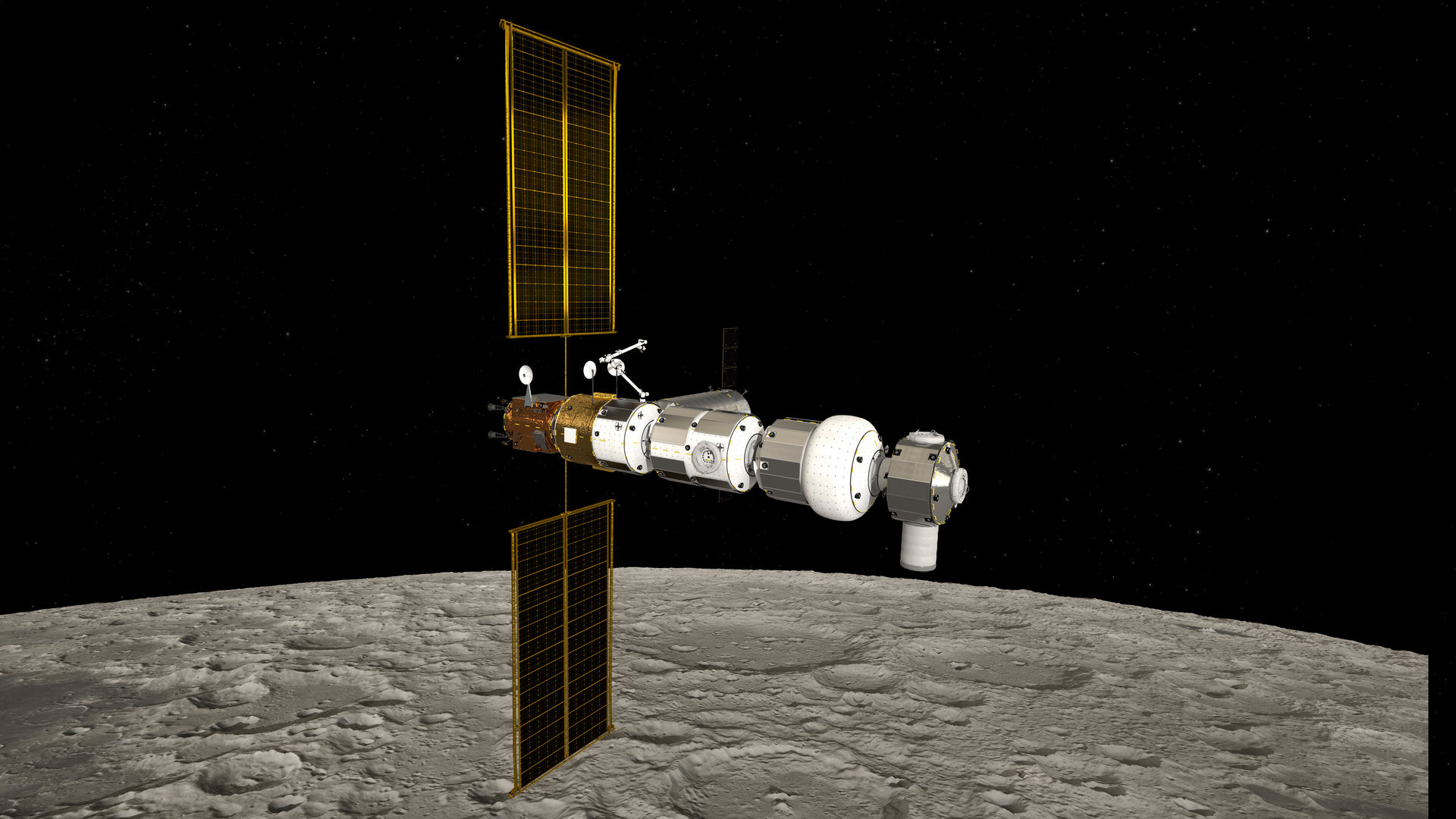

6) Gateway space station

The Gateway space station is the latest in a long evolution of space station and space base concepts for astronauts; one of the first NASA mentions of a "Deep Space Gateway" orbiting the moon was in 2017, and the facility was incorporated into early Artemis program plans as a waystation for astronauts bound for the lunar surface. In 2020, Gateway was removed from the "critical path" of the first lunar landing in 2024, but it remains one of NASA's planned successors to the International Space Station program. Like ISS, Gateway will represent an international partnership but unlike ISS, Gateway will not be permanently occupied.

Some of the planned elements of Gateway include a power and propulsion module built by Maxar; a habitation and logistics outpost built by Northrop Grumman; the European System Providing Refueling, Infrastructure and Telecommunications or ESPRIT built by Thales Alenia; the International Habitation Module built by Thales Alenia and a robotic arm called Canadarm3 built by MDA. SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rocket will deliver the first two segments, NASA announced early in 2021. The design for Gateway is still evolving and NASA may add more elements.

7) Gateway tug plans

Some plans for the lunar Gateway also include cargo tugs, although there are no firm plans yet to build such vehicles. At least as early as 2017, a peer-reviewed paper in the journal Acta Astronautica proposed using an electric-powered lunar space tug to service Gateway. The aim was to reduce the cost of moon flights by carrying logistics modules (with supplies on board) between the Earth and the moon. The tug would operate between the Earth and the moon for several flights, and would require a spaceborne depot for refueling operations.

8) Shackleton Crater surface base

In 2012, scientists investigating the lunar south pole's Shackleton Crater in then-unprecedented detail identified ample supplies of water frozen into the lunar surface in the region. Since then, observations from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and other spacecraft have confirmed that there's water ice in the region. Would-be lunar explorers believe that such water can be separated into its hydrogen and oxygen components for rocket fuel or for astronaut air supply. That said, the technology to turn water into fuel is still in early development; one of the cubesats that will fly with NASA's SLS around the moon will test a water-electrolysis propulsion system in space.

In 2020, NASA revealed early plans for its Artemis Base Camp near Shackleton Crater. As the facility evolves and grows, it will require supplies for water, waste disposal, communications, landing vehicles and shielding astronauts from radiation, NASA stated. The base will also include two mobility systems: a lunar terrain vehicle for astronaut surface movement, and a habitable mobility platform that could support trips away from base for up to 45 days. The facility may also facilitate experiments, dealing with lunar dust, in-situ resource utilization or a far-side radio telescope.

9) Artemis spacesuits

NASA last used a spacesuit on the lunar surface in 1972; its current generation of space station spacesuits for floating spacewalks, the Extravehicular Mobility Unit, was introduced in 1981 but isn't appropriate for conditions on the moon. Seeking upgraded options, NASA unveiled two spacesuit prototypes in 2019 for Artemis. The first is the Exploration Extravehicular Mobility Unit (xEMU), a red, white and blue suit designed to be worn during lunar surface expeditions. The second is the Orion Crew Survival System, a bright orange pressure suit to be worn by astronauts in the Orion capsule when they launch into space and return to Earth.

As of October 2020, NASA said it planned to make five xEMU suits in the initial batch — one for design verification, one for qualification testing, one to be tested in orbit on the International Space Station, and two for the first moon-landing mission, Artemis 3. NASA also requested information on possible commercial participation in spacesuit development in April 2021. But in August 2021, NASA's Office of the Inspector General cited a then 20-month delay in xEMU development that made a 2024 deadline for implementing on the moon "not feasible."

10) Robot missions

NASA is planning to use privately developed landers, rovers, payloads and other commercial products on the moon under its Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. CLPS first was suggested in April 2018 in the wake of the cancelation of the Resource Prospector rover, with NASA saying it instead planned to focus on a "series of progressive robotic missions" to the moon. The agency released a draft request for proposals in April 2018, with the first batch of U.S. companies selected in November 2018.

As of August 2021, it's unclear which CLPS mission will be first to land as scheduled 2020 launches have faced continuing delays. Astrobotic's Peregrine Mission One (PM1) plans to send more than two dozen payloads to the moon in 2022, according to SpaceNews. Intuitive Machines is also set to deliver NASA's Polar Resources Ice Mining Experiment (PRIME-1) in 2022.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.