Mobile Stargazing: Binocular Astronomy Tips and Targets for Summer 2017

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

In the Oct. 21, 2016, edition of Mobile Astronomy, we examined how to use binoculars for astronomy, explained how they work and what to shop for, and suggested some night-sky objects to look at. This time, we'll cover some tips for making binoculars work better for you, highlight a type of binoculars that helps with unsteady hands and share a variety of targets to look for this summer.

Using binoculars for astronomy

Binoculars consist simply of a matched pair of small telescopes precisely mounted together to deliver a stereo image to your two eyes. The lenses at the front are called objectives. As with any optical device, the larger the area of those lenses, the more light they collect and concentrate into your pupils.

The small lenses you look into are called eyepieces or oculars, and they do the job of magnifying what you see. In binocular specification numbers, such as 7 x 50, the second number is the diameter of the objective lenses in millimeters and the "7x" means the binoculars will magnify by seven times. [Best Astronomy Binoculars (Editors' Choice)]

Binoculars are terrific for astronomy because they have a much wider field of view than telescopes, making it far easier to hunt for objects in the sky — plus, binoculars are easy to carry around and require no setup. Binoculars' limited magnification, usually less than 10 times, is more than enough for many classes of astronomical objects. And the light-gathering ability of binoculars raises dim objects, like comets or nebulas, to visibility. Most people find that viewing with two eyes is less straining than single-eyed telescope viewing, too. In fact, many beginner stargazers spend months or years learning the sky with binoculars before graduating to telescopes.

Most binoculars work perfectly well for astronomy. But if you are buying with astronomy in mind, choose a pair that has large objective lenses, but which is still comfortable for you and the kids to hold for extended periods. You can also invest in a bracket for mounting larger binoculars on a tripod. To find binoculars compatible with that setup, check for a mounting-screw receptacle. It might be hidden under a removable cover.

Coated optics are essential for brighter views with high contrast and for avoiding unwanted color fringing on the edges of bright objects. Better binoculars will also allow one ocular to be focused independently, in case the prescriptions in your two eyes differ. If you plan to use your binoculars while wearing glasses, look for models with more than 15mm (0.6 inches) of eye relief (the distance between the ocular lens and your eyes). Due to manufacturing variations, it's always a good idea to try binoculars in the store, so you can be sure they achieve focus and deliver a crisp, blended image.

Most people naturally hold binoculars with their hands relatively close to their faces and within reach of the focusing ring. For better results, though, focus the binoculars, and then move your hands closer to the objective lenses while resting the rubber ocular guards against your face. You'll find that the view will be much steadier. Sitting or leaning against something sturdy are also helpful.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another surefire way to get steadier views is to use image-stabilized binoculars (ISBs). These have an internal suspension system that reduces the effects of your hands' movements. The electronics operate on installed batteries and have a button that engages the stabilization. Although these binoculars can be pricey, I have tried them, and the difference is amazing! Gary Seronik, the editor of SkyNews magazine, has written an extensive review of the best ISBs for astronomy on his website.

Summer binocular targets

Here are a variety of objects you can look at using binoculars of any size this summer. Your favorite astronomy sky-charting apps will include these objects. Simply set the app to your observing time and date, and search using the names I've provided. The app will show you where in the sky these objects are, including any nearby "signpost" stars. The better apps, such as SkySafari 5, will also provide a wealth of information about the objects and show you high-resolution color images.

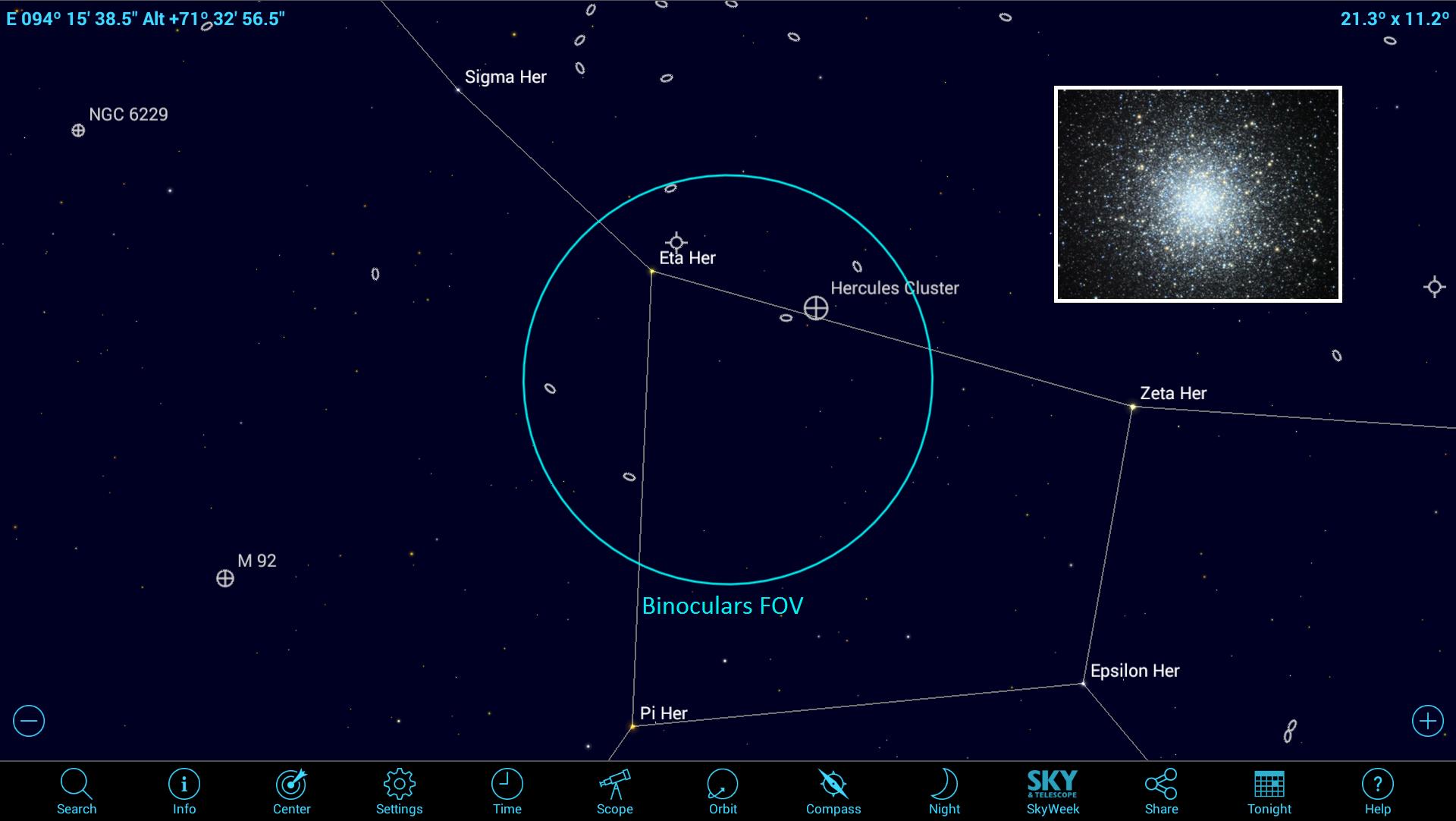

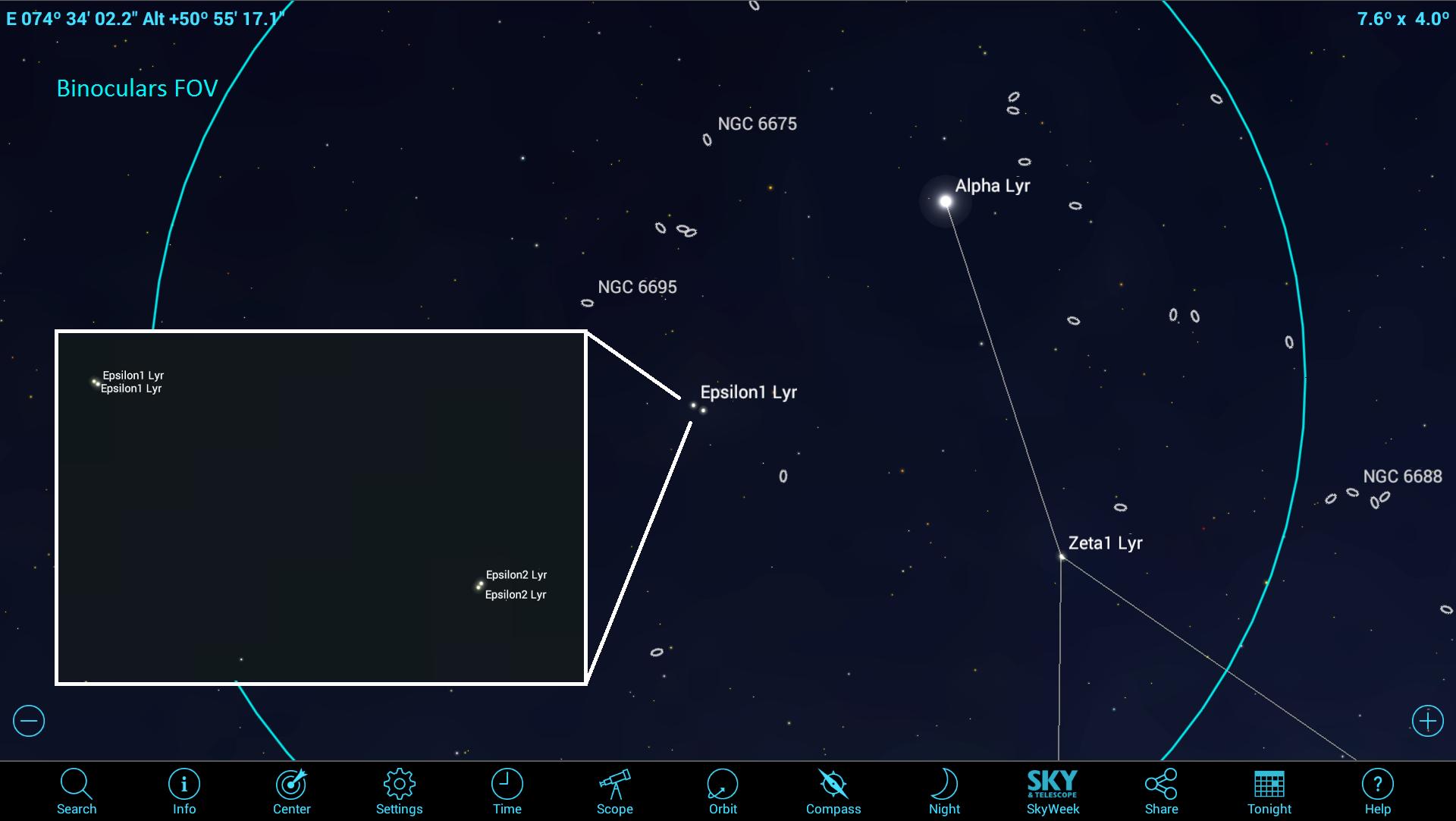

SkySafari 5 allows you to display a circular field-of-view indicator for your binoculars to help you judge how large objects will appear in them and to aid in locating the objects with respect to nearby bright stars. In the Settings menu, select Display. A list of predefined fields of view will appear. You may select one that matches your setup or customize your own. Ensure that the option to "Show even if not connected to telescope" is enabled. Exit the menu, and a blue circle should appear at the center of the display.

The Big Dipper

The Big Dipper is the best-known asterism in the sky. (An asterism is an obvious shape composed of a limited number of, usually, naked-eye stars.) The dipper is only part of the larger, surrounding constellation, Ursa Major (the Big Bear). The SkySafari 5 app allows you to highlight asterisms and their names. In the Settings menu, select Constellations. Scroll down and enable the Show Asterisms and Show Names boxes. Now, the display will overlay the asterisms on the constellations and you can trace them out in your binoculars.

While you're touring the Big Dipper, look at the star that marks the bend in the handle. This is Mizar. Just above the handle, and close beside Mizar, is a much fainter star named Alcor. Most people can see both stars with unaided eyes. Known as the Horse and Rider to the ancient Arabs, these stars were used for eye tests in that era. Viewed in binoculars, Mizar readily splits into a double star, with one slightly brighter than the other. These two stars are believed to be revolving about one another with a period of 5,000 years.

The Little Dipper is positioned with its smaller bowl pouring into the Big Dipper's bowl and its handle pointed the opposite direction. Other than Polaris at the handle's end and Kochab at the bowl's outer rim, the stars of the Little Dipper are difficult to see under light-polluted skies. With binoculars, however, you will have no trouble seeing all seven stars.

The Summer Triangle and the Coathanger

The Summer Triangle is another asterism. Three bright white stars mark out a large, slim triangle about 34 degrees long (more than three fist diameters at arm's length) and 24 degrees tall. In early summer, the feature dominates the eastern evening sky, with Deneb on the left, Altair to the lower right and Vega high between them. The Milky Way bisects the triangle, so the area is populated with a wealth of star fields, dark dust lanes and nebulas — all splendid viewing in binoculars. Use your astronomy app to zoom in on the area. It contains many Messier list and NGC (New General Catalog) binocular targets. Try to find them by hopping among the prominent stars.

Next, look for the Coathanger asterism, a small grouping of dim stars located almost exactly halfway between Vega and Altair. The stars combine to form a short, straight bar with a hook (on the Altair side). The entire shape will fit within your binocular field of view. Under very dark skies, you might be able to spot it with naked eyes, too!

The Milky Way to the left of Deneb is also a treasure trove of binocular sights, including the North American nebula, the Messier 39 open star cluster and more. And late-night observers can hunt down the Andromeda galaxy, wide as six full moons and perfect for binoculars!

Epsilon Lyrae

Epsilon Lyrae is the designation given to a star in the constellation of Lyra (the Lyre), and it poses a fun challenge for amateur skywatchers, even during full-moon periods. The star sits about a finger's width to the lower left of Vega. To the naked eye, it looks like a single star, but if you have even weak binoculars (or very sharp eyesight), you can see that it's a pair of stars. Under more magnification, such as a backyard telescope, each of the two stars divides in two, making it a "double-double," its common nickname.

Messier 13 globular cluster

Hercules contains one of my favorite objects, a globular cluster known as the Great Hercules cluster or Messier 13. This object is a tightly packed ball of about 300,000 ancient stars. At magnitude 5.9, it is visible with unaided eyes under dark skies, appearing as a faint smudge. But binoculars or telescopes reveal more. The cluster is located along the western (right) edge of the keystone-shaped body of Hercules, about one-third of the way from the wide end.

Midway between Hercules' knees, there is another, smaller globular cluster called Messier 92 that is also readily visible in binoculars. A third, fainter globular cluster designated NGC 6229 is located 6.5 degrees, or a palm's diameter, above Messier 92.

The Great Hercules globular cluster was first observed by British astronomer Edmund Halley in 1714. It is a relatively close object, at 21,500 light-years away from Earth, making it a bright magnitude 5.8, and it covers an area of sky 20 arc-minutes across (two-thirds of the moon's diameter).

The summer southern sky

If you follow the Milky Way downward to the right, beyond the summer triangle, you enter the richest part of the night sky available for mid-northern observers. The Wild Duck cluster, also known as Messier 11, is a large open star cluster with several hundred stars packed into an area of sky equivalent to the apparent diameter of the moon. One of the cluster's early observers coined its name. See if you agree that it resembles a wedge of flying birds.

Another very rich star field in binoculars is the Sagittarius star cloud, or Messier 24. It is close to the center of Earth's Milky Way galaxy. Observers in a dark sky should also try observing the several bright nebulas in the region, particularly the Eagle (Messier 16), Omega (Messier 17), Trifid (Messier 20) and Lagoon (Messier 8) nebulas.

One can spend hours in a comfortable chair scanning the southern summer sky for open star clusters, globular clusters and nebulas. Switch on your app's night mode to preserve your dark adaptation and use the app to identify the objects you find. Keep a record of what you find!

Going beyond: The first-quarter moons and planets

Don't forget about the moon and planets this summer. While binoculars can't reveal details on Jupiter, you can certainly watch the four Galilean moons dance around the planet, changing their positions from night to night. Jupiter is observable during evenings until September, spending the entire summer apparition in the western sky in Virgo, near that constellation's brightest star, Spica. [Photos: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter]

Saturn will spend the summer of 2017 near the rich star fields of the Milky Way. Look for it low in the southern sky in the evening. Binoculars will reveal a hint of the rings and the planet's largest moon, Titan. Use your app to find out where Titan is while you are observing. And extremely bright Venus will be visible all summer in the eastern, predawn sky.

Despite its eye-catching brilliance, a full moon is a rather dull sight in binoculars, because there are no shadows cast on the surface. But on the evenings, after new moon until first quarter, the moon is a spectacular sight in binoculars and telescopes, because the sun's light is striking the hemisphere facing the Earth at a shallow angle. All along the terminator, the boundary that separates the lit and dark sides from pole to pole, the brilliantly lit crater rims and mountain peaks cast long black shadows. Every evening, the terminator shifts farther to the moon's west (east, for Earth observers), highlighting new vistas.

As a bonus, the first-quarter moon is always conveniently positioned in the western evening sky. This summer's best evenings to observe the moon are June 26-30, July 25-30 and August 24-29.

Binoculars are also perfect for looking at earthshine, sometimes referred to as "the new moon in the old moon's arms." It occurs on the first few evenings after new moon, when sunlight reflected off the Earth slightly illuminates the dark portion of the moon above the lit evening crescent.

In future columns, we'll talk about controlling your go-to telescope with your phone, tour southern skies not visible from the Northern Hemisphere, discuss galaxy types and do more. Until next time — keep looking up!

Editor's note: Chris Vaughan is an astronomy public outreach and education specialist, and operator of the historic 1.88-meter David Dunlap Observatory telescope. You can reach him via email, and follow him on Twitter @astrogeoguy, as well as on Facebook and Tumblr.

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.