Leonardo da Vinci's lost sketches show early experiments to understand gravity

Leonardo da Vinci's centuries-old sketches reveal he may have understood key aspects of gravity long before Galileo, Newton and Einstein.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Leonardo da Vinci's centuries-old sketches reveal he may have understood key aspects of gravity long before Galileo, Newton and Einstein.

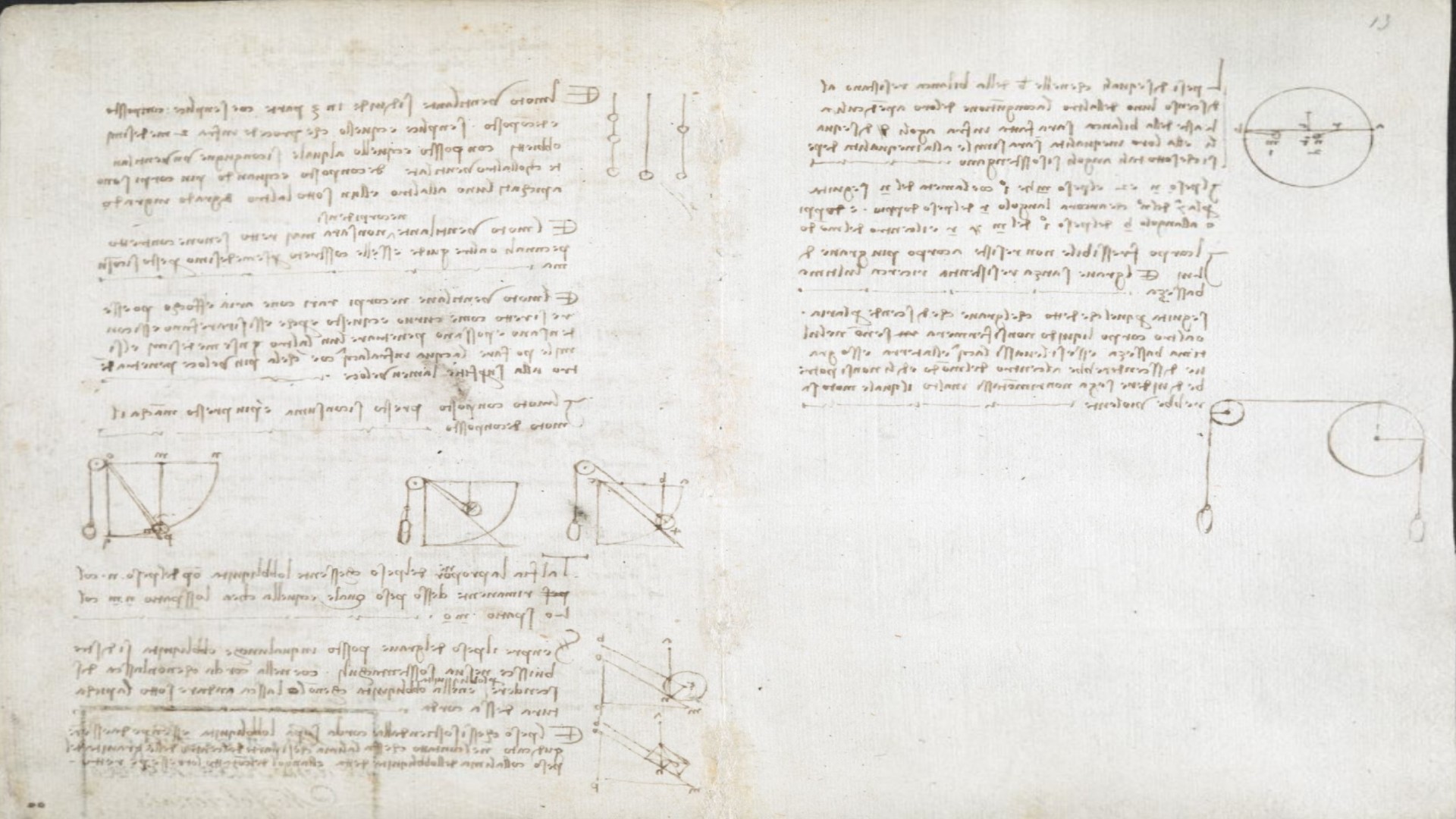

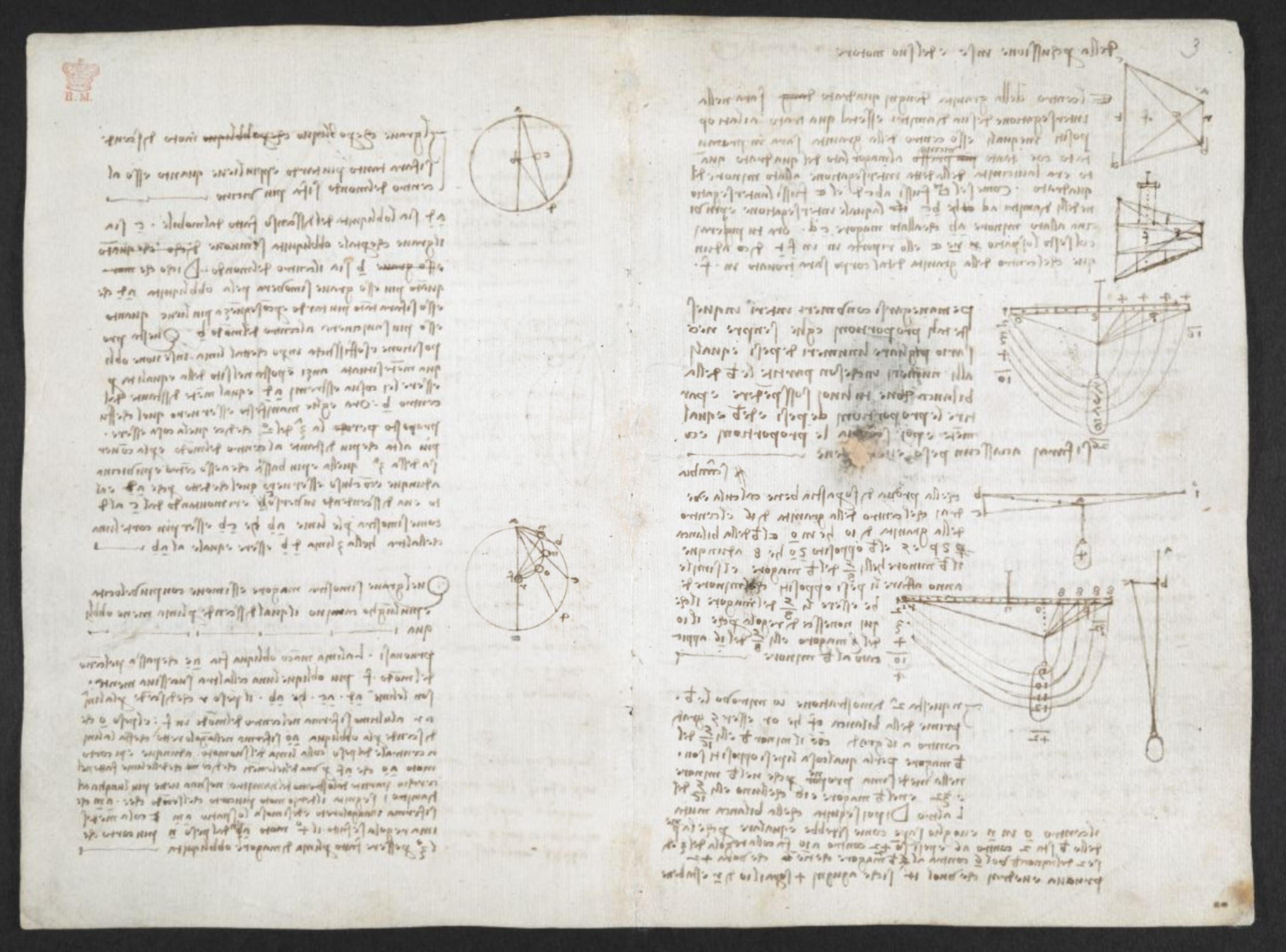

A recent study from the California Institute of Technology examined diagrams in da Vinci's notebooks that had been long forgotten about. These notebooks, which have now been digitized, show experiments from the early 1500s of particles falling from a pitcher, demonstrating gravity is a form of acceleration, according to a statement from the university.

"It wasn't until 1604 that Galileo Galilei would theorize that the distance covered by a falling object was proportional to the square of time elapsed and not until the late 17th century that Sir Isaac Newton would expand on that to develop a law of universal gravitation, describing how objects are attracted to one another," according to the statement. "Da Vinci's primary hurdle was being limited by the tools at his disposal. For example, he lacked a means of precisely measuring time as objects fell."

Related: Einstein's theory of general relativity

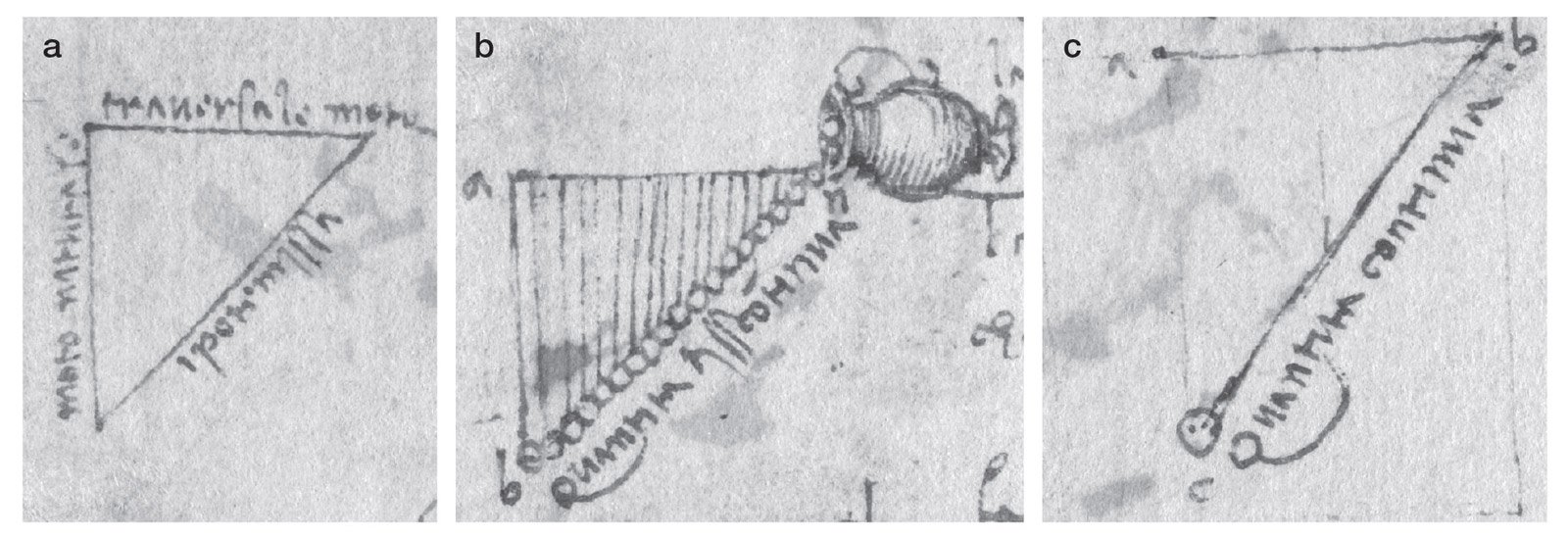

Some of da Vinci's sketches show triangles created by particles pouring out of a pitcher when moved along a straight path parallel to the ground. What da Vinci realized in these experiments was that if the pitcher moves at a constant speed, the line created by falling material is vertical, whereas if the pitcher accelerates at a constant rate, the falling material creates a slanted line — or the hypotenuse of an isosceles triangle formed between the start and end point of the falling material.

The sketches also showed that if the pitcher's motion is accelerated at the same rate that gravity accelerates the falling material, it creates an equilateral triangle, which da Vinci identified as "Equatione di Moti," meaning "equalization (equivalence) of motions."

"What caught my eye was when he wrote 'Equatione di Moti' on the hypotenuse of one of his sketched triangles — the one that was an isosceles right triangle," Mory Gharib, lead author of the study and professor of Aeronautics and Medical Engineering at Caltech, said in the statement. "I became interested to see what Leonardo meant by that phrase."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

When analyzing the sketches, the researchers had to translate da Vinci's Italian notes, which were written in his famous left-handed mirror writing that reads from right to left. The researchers then used computer models to replicate da Vinci's experiments.

Da Vinci's notes acknowledge that the velocity of the falling material accelerates downwards, and that as the particles fall, they are no longer influenced by the pitcher, but instead accelerated by only gravity pulling them downward. However, he was unable to formulate his observations into an equation at the time.

"What we saw is that Leonardo wrestled with this, but he modeled it as the falling object's distance was proportional to 2 to the t power [with t representing time] instead proportional to t squared," Chris Roh, co-author of the study and assistant professor at Cornell University, said in the statement. "It's wrong, but we later found out that he used this sort of wrong equation in the correct way."

When modeling the water vase experiments, the team yielded the same error da Vinci did centuries ago.

"We don't know if da Vinci did further experiments or probed this question more deeply," Gharib said in the statement. "But the fact that he was grappling with this problem in this way — in the early 1500s — demonstrates just how far ahead his thinking was."

Their findings were published Feb 1 in the journal Leonardo. The original experiment sketches are captured in the Codex Arundel, a collection of papers written by Leonardo da Vinci, which can be viewed online, courtesy of the British Library.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.