Mars Science Laboratory Delayed to 2011

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

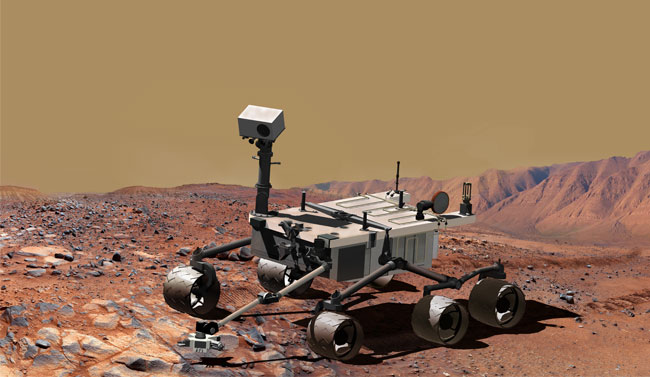

The MarsScience Laboratory mission, a jumbo rover originally slated to launch for thered planet next year, has been delayed until 2011, NASA announced today.

"Wewill not be ready to launch by the hoped-for date next year," said NASA AdministratorMichael Griffin at a briefing.

A major review ofthe mission conducted earlier this year had concluded that MSL "had asolid chance of making the 2009 launch" if the launch window was extendedinto October 2009, which was done, and an additional $200 million was added tothe project, said Ed Weiler, associate administrator for NASA's Science MissionDirectorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

But newtechnical issues that came up since that review as well as missed deliveryschedules have prompted NASA officials to further delay the mission to avoid a"mad dash to launch," Weiler said. "Failure on this mission isnot an option, the science is too important," he added.

The MSLrover has a complex suite of instruments that can test the Martian surfacefor signs of past potential habitability, including onboard chemistry labs anda laser that can zap rocks to determine their composition.

The rovermay also leave some of its originally-plannedequipment behind.

The roveris much larger than its Mars Exploration Rover (MER) cousins, Spirit and Opportunity,weighing in at about 2,040 pounds (925 kg) and currently still operating onMars. MSL will also use a completely novel way of getting down to its landingsite called Sky Crane, which will have cords that attach it to the lander. Asthe rover falls to the surface, the Sky Crane's thrusters should slow therover's descent as the crane uses the cords to lower the lander.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The missionnow is delayed for two years because launch windows to Mars are few and farbetween because of the relative positions of Mars and Earth.

"We'rereally only a few months behind schedule, not two years behind schedule,"said Doug McCuistion, director of the Mars Exploration Program at NASAHeadquarters.

Landingsites for the mission, which were recently whittled down to a final four, willlikely be unaffected by the delay, McCuistion said.

The delaywill add an estimated $400 million to the mission, which could impact otherNASA programs, McCuistion said. NASA will aim to delay programs instead ofcutting any, officials said at a briefing today.

Theparticular technical issues delaying the mission are with the rover'sactuators, which McCuistion describes as a combination of a motor and a gearbox. The actuators control anything in the rover that moves, including thewheels and robotic arms.

"They'reabsolutely crucial to the success of this mission," McCuistion said.Without them "we'd basically have a metric ton of junk on thesurface" of Mars, he added.

Most of therover's hardware has been completed and the two years until launch will bespent dealing with the actuators and any other technical issues that crop up.

"It'snot like it's going in a big plastic bag and sitting in the corner for twoyears," McCuistion said.

Griffinsaid: "I have full confidence in the JPL [Jet Propulsion Laboratory] teamto work through the difficulties."

- Video: Next Big Step on Mars, Part 1

- Video: Next Big Step on Mars, Part 2

- Future of Mars Exploration: What's Next?

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.