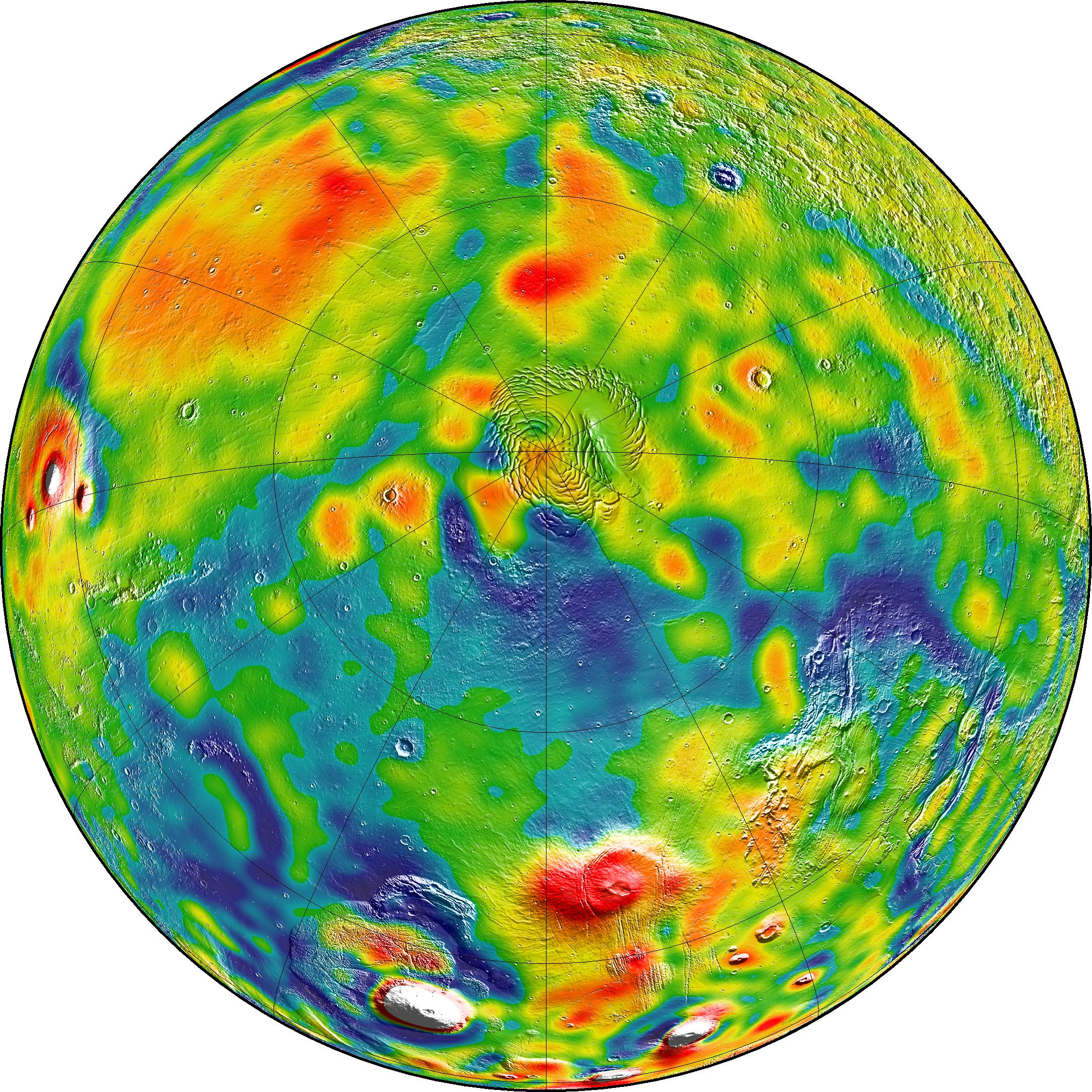

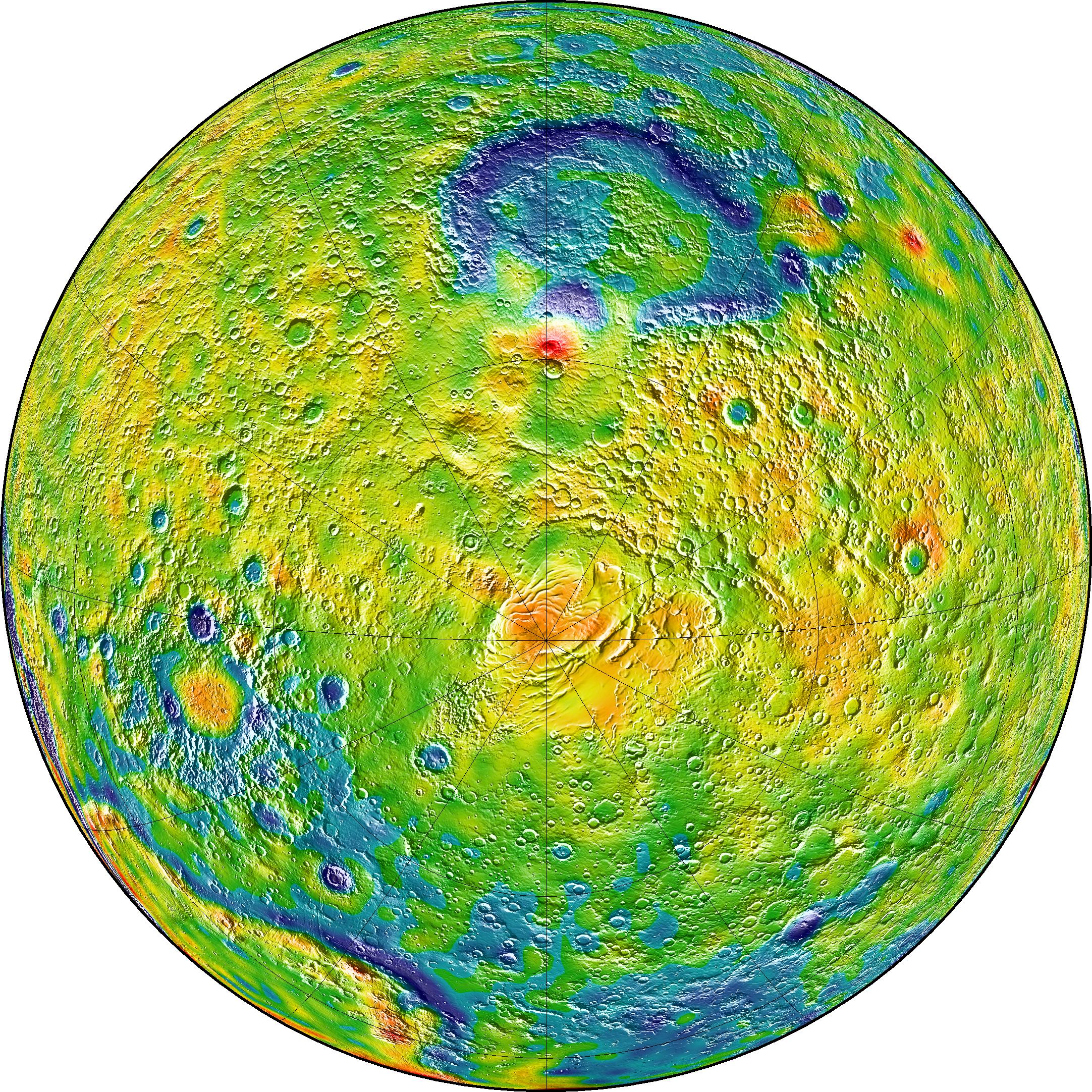

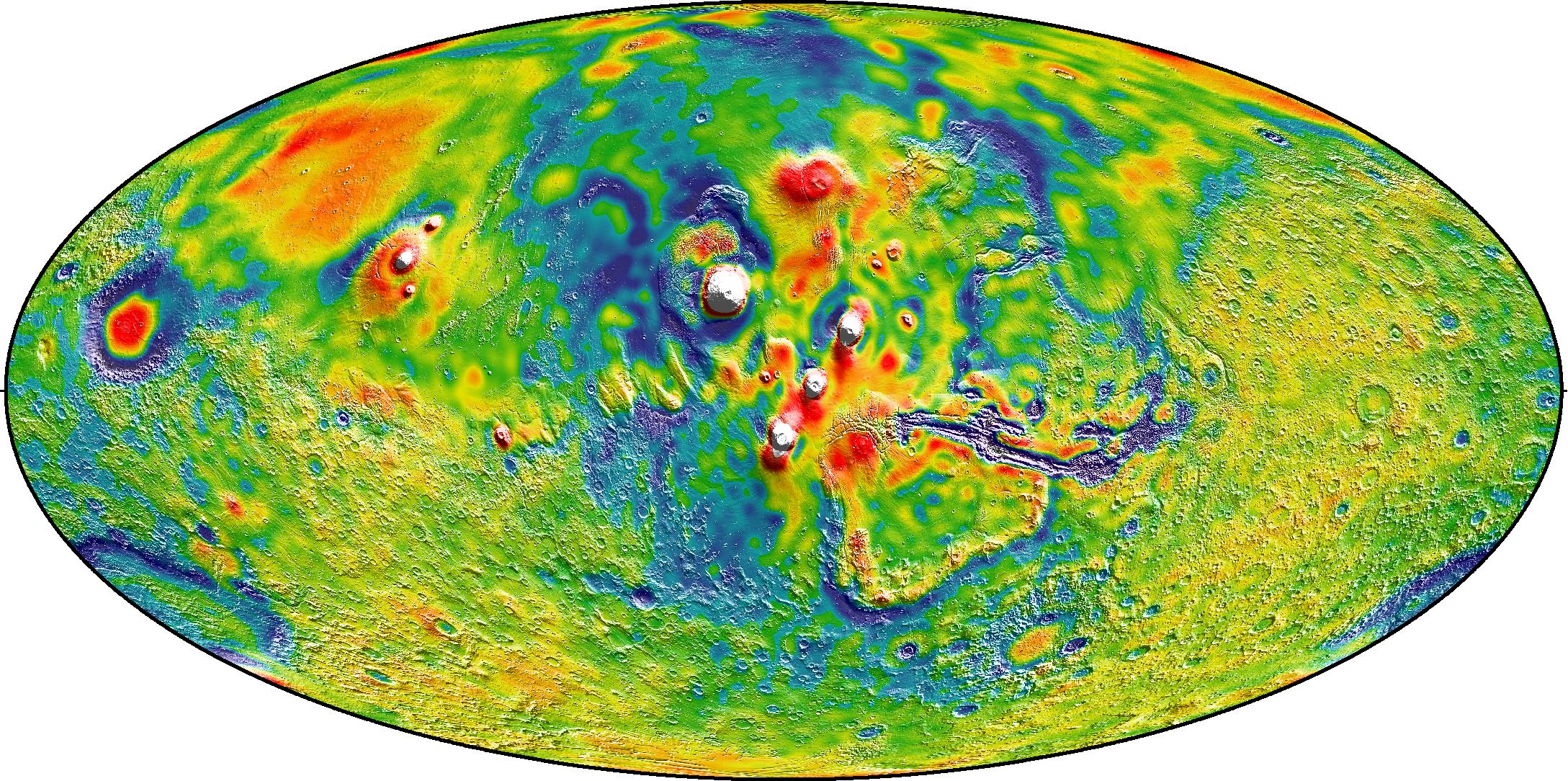

NASA: New Mars Gravity Map Is the Best Ever

A new map of Mars' gravity, which NASA is touting as the best one ever made, will make it easier for future spacecraft to make their way to the Red Planet. The new Martian gravity map also reveals clues into how the planet's past was shaped, scientists say.

The new map of Mars' gravity was generated by scientists using data from three NASA spacecraft — the Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter —which mapped the Red Planet from orbit. The data allowed NASA to create a video look at Mars' gravity, as well.

"Gravity maps allow us to see inside a planet, just as a doctor uses an X-ray to see inside a patient," lead author Antonio Genova of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement. [The 7 Biggest Mars Mysteries]

"The new gravity map will be helpful for future Mars exploration, because better knowledge of the planet's gravity anomalies helps mission controllers insert spacecraft more precisely into orbit about Mars. Furthermore, the improved resolution of our gravity map will help us understand the still-mysterious formation of specific regions of the planet."

The new map has also revealed additional insights about Mars. By observing tides in the Martian crust and mantle created from the gravitational pull of the sun and Mars' two moons, the team confirmed that the core of Mars has a liquid exterior of molten rock. They also looked at changes in Martian gravity — which is about one-third that of Earth's gravity — over 11 years (the same as the sun's cycle of activity). An examination of these changes gave them new insights into how much of the polar ice cap's carbon dioxide freezes out of the atmosphere during winter. The team also gained insights into features across the north-south boundary of Mars, and how carbon dioxide moves between the south pole and the north pole.

NASA created the map by tracking small fluctuations in the orbits of three spacecraft over 16 years using the Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The gravity in different regions of Mars changes according to what is below; mountains exert a slightly stronger tug and canyons a slightly weaker one, for example. The team also had to take into account orbital fluctuations from other sources, such as sunlight's force on the vehicle's solar panels and drag from Mars' atmosphere.

"With this new map, we've been able to see gravity anomalies as small as about 100 kilometers (about 62 miles) across, and we've determined the crustal thickness of Mars with a resolution of around 120 kilometers (almost 75 miles)," Genova said in the NASA statement. "The better resolution of the new map helps interpret how the crust of the planet changed over Mars' history in many regions."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists also gained more information about why there is an area of lower gravity between Acidalia Planitia and Tempe Terra. An earlier explanation was that, billions of years ago, when the Red Planet was warmer and wetter, there were channels under the soil that moved water and regolith from Mars' south highlands to its north lowlands.

The new map, however, suggests that the lower gravity is not solely due to these buried channels, because it shows some features running against the downhill slope of water. The team suggests that this may instead be due to flexing of the lithosphere (the outermost layer of the planet) that occurred when the volcanic Tharsis region formed. The volcanoes in Tharsis are so large that their weight caused the lithosphere to cave in slightly.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.