Saturn's Weirdest Ring Explained: Ancient Collision Caused It

The mystery behind the origin of what may be Saturn's oddest ring and its two companion moons may finally be solved: They came from an ancient, catastrophic collision, researchers say.

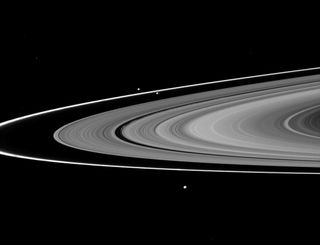

The rings of Saturn are the most outstanding features of the gas-giant planet. In 1979, NASA's Pioneer 11 probe discovered that about 2,100 miles (3,400 kilometers) beyond the outer edge of Saturn's main A, B and C rings exists what some astronomers call Saturn's weirdest ring, the F ring. This constantly shifting band of icy material possesses an extraordinary level of complexity, with bends, kinks and bright clumps that can give it the illusion of being braided. Prior estimates suggest the F ring is several million years old. [Video: Saturn's Strange F Ring Explained]

Prometheus and Pandora, two of Saturn's more than 60 moons, flank the F ring on either side, weaving inside and outside the ring. These moons apparently act like shepherds, herding the flock of icy particles making up the F ring into a narrow band about 60 miles (100 km) wide. However, the way in which this chaperoning arose was a mystery.

As Saturn's rings evolved, icy particles clumped together to form moonlets, piles of rubble that eventually spiraled outward and slammed into each other, forming Saturn's largest moons. Past research suggested the collision between two of these fragile moonlets created the F ring.

To learn more about how the F ring was formed, planetary scientists Ryuki Hyodo and Keiji Ohtsuki at Kobe University in Japan simulated collisions between moonlets at the outer edge of Saturn's main rings, with each moonlet composed of 5,000 spherical particles. Their models analyzed moonlets with a variety of compositions, and accounted for the effects that Saturn's gravitational pull would have on the debris from collisions.

The researchers found that if colliding moonlets were made up entirely of small, icy particles, these piles of rubble would have completely disintegrated after collisions, resulting in only a ring. However, if the moonlets had denser cores made up of rocks or large chunks of ice, they might not have completely destroyed each other. This would result in not only a ring but also two remnant moons with about half of the mass of the originals. This is a close match to what astronomers see with the F ring and its shepherd moons. Indeed, the researchers noted that NASA's Cassini spacecraft found that both Prometheus and Pandora had dense cores.

The scientists detailed their findings online Aug. 17 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The implications of these findings are not limited to Saturn's F ring system, Hyodo said. "In our solar system, we have another narrow ring with shepherd moons on both its sides, the 'epsilon ring' around Uranus," Hyodo explained. "Seemingly unusual narrow ring systems with shepherd moons could be ubiquitous around giant planets."

In the future, the researchers will simulate the long-term evolution of the F ring to shed light on its ongoing evolution, Hyodo said. Ohtsuki added that more-accurate estimates of the F ring's mass and the internal structure of the shepherd moons would help researchers deduce what these satellites' progenitor moonlets and collisions were like.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us

Most Popular