November's new moon lets the winter constellations shine bright tonight

Get out and soak up the stars tonight.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Tonight's new moon makes this is a perfect night to get out and take in the night sky.

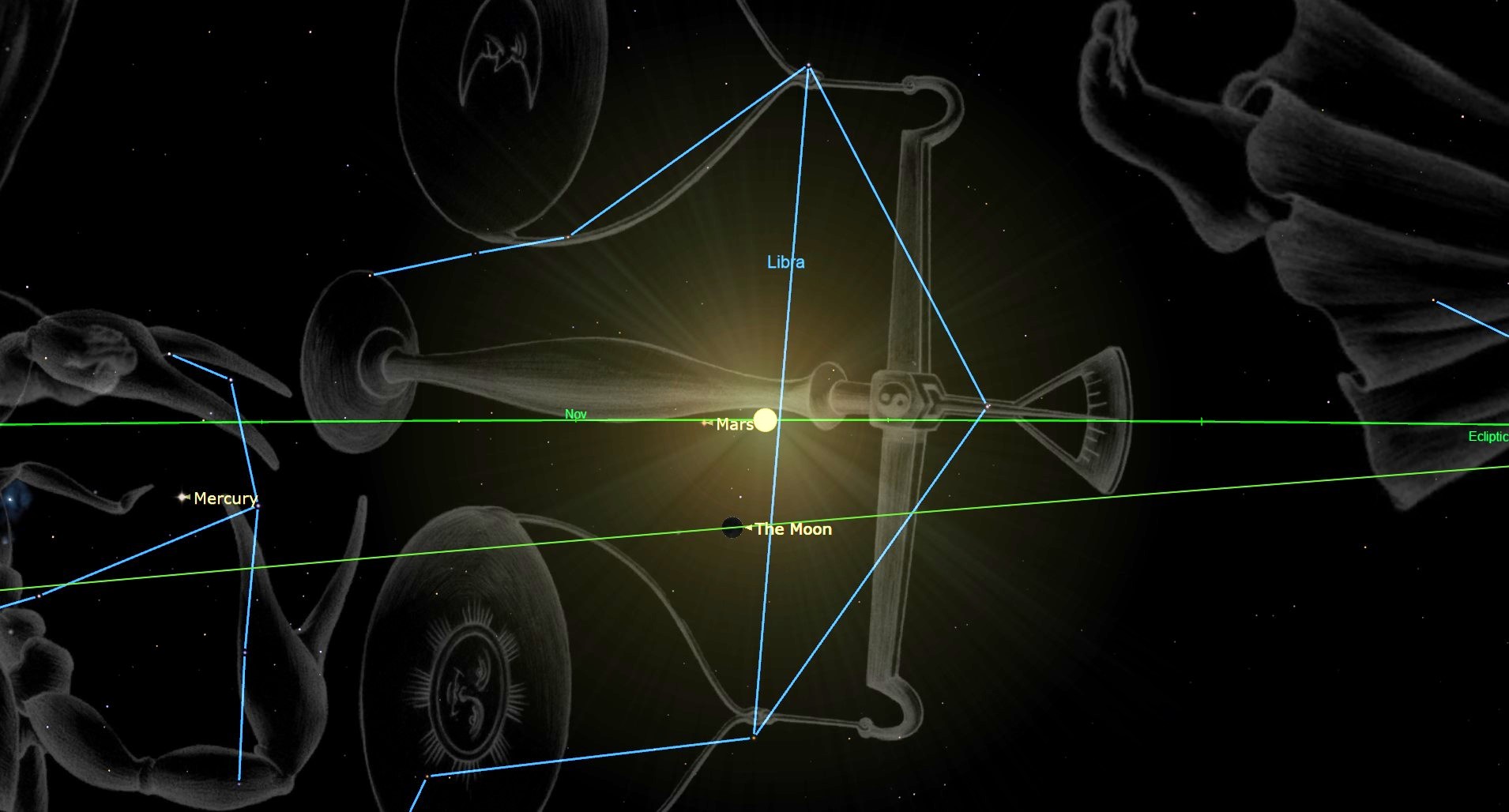

The new moon occurs on November 13, at 5:57 a.m. Eastern Time (0927 GMT), per the U.S. Naval Observatory; a day later the moon will make a difficult to observe pass by Mercury.

The new moon occurs when the moon is between the sun and Earth; strictly speaking it shares the same celestial longitude as the sun; it reaches this position approximately every 29.5 days. Celestial longitude is a projection of the Earth's longitude lines on the celestial sphere; when two bodes share the same longitude that is called a conjunction. If one draws a line from Polaris, the North Star, due south toward the sun, that line also goes through the moon. Timing of lunar phases depends on the position of the moon relative to Earth, so the differences is when a lunar phase occurs depends on one's time zone.

Related: Full moon calendar 2023: When to see the next full moon

New moons are invisible unless they pass directly in front of the sun, making a partial or total solar eclipse. Such an alignment occurred in October; the first solar eclipse visible in the U.S. since 2017.

In this case, the moon will do what it does most of the time, and pass by the sun without blocking any of its light. The reason new moons don't create eclipses every month is because the moon's orbit is slightly inclined to the that of Earth's, so the three bodies aren't always perfectly lined up.

Visible (and invisible) planets

Want to see stars and planets in the night sky during new moons? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

On the night of the November new moon, the sun sets in New York at 4:40 p.m. local time. With the sun setting relatively early, by 6 p.m. one will be able to see Jupiter and Saturn. Saturn will appear almost due south; the planet sets at 11:57 p.m. Saturn will not be especially high in the sky for mid-northern latitudes; from New York City (at 40 degrees N) it is about 35 degrees above the horizon – approximately a third of the way to the zenith (straight up).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jupiter, meanwhile, will be in the eastern sky, about 21 degrees high. Jupiter reaches its highest point, called transit, at 10:54 p.m. when it is a full 62 degrees above the horizon, making it an easy target for small telescopes and binoculars as well as naked-eye viewing. The planet sets at 5:43 a.m.

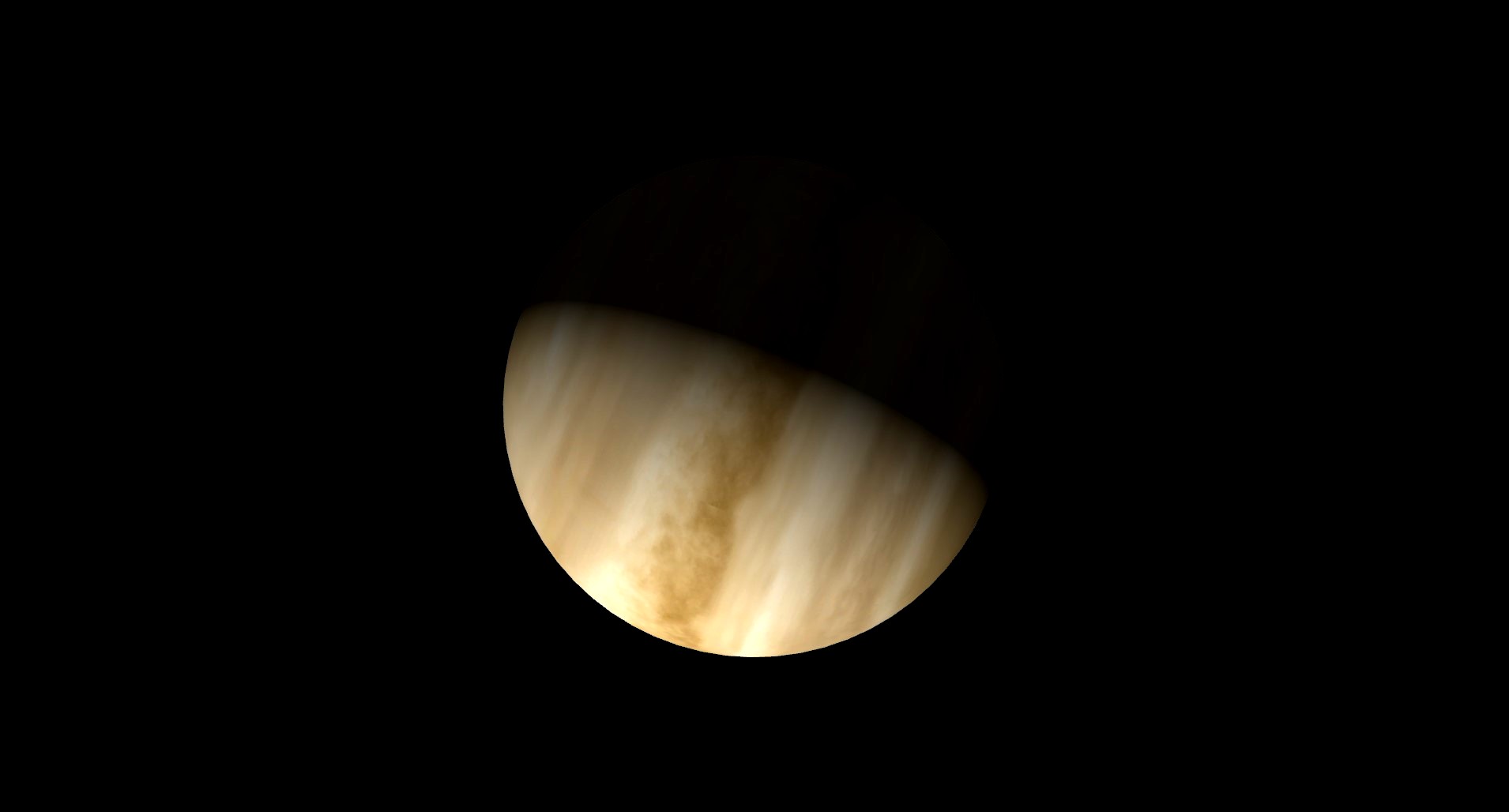

Mars and Mercury are currently both lost in the solar glare. But Venus is a prominent morning star; on the night of the new moon (Nov. 13) the planet rises at 2:49 a.m. in New York and by sunrise (at 6:40 a.m. local time) the planet is 40 degrees above the southeastern horizon. Venus is bright enough that it is visible even when the stars have largely faded; from Manhattan, for example, one can look southeast and see it almost immediately as the sky gets brighter.

Southern Hemisphere sky watchers will see Jupiter and Saturn higher in the sky; while the sun sets later (as we approach the austral summer months) the increased altitude means they are visible longer. For example, in Buenos Aires, where the new moon occurs at 6:27 a.m. local time on Nov. 13, the sun sets at 7:34 p.m. and the sky is fully dark by 9 p.m. At that point Saturn has already moved to the northwest, and it is 60 degrees above the horizon. The planet sets at 2:15 a.m. Nov. 14. Jupiter rises just over an hour before sunset at 6:25 p.m. local time and sets at 5:18 a.m., so it is visible almost all night. At 9 p.m. it is in the northeast, 27 degrees high.

The one-day-old moon will be in conjunction with Mercury on Nov. 14 at 9:39 a.m. Eastern Time, passing just 1 degree and 39 minutes south of the moon. From Northern Hemisphere locations the pair will be too close to the horizon to see – in New York they won't be more than 2 degrees above the horizon at dusk, according to in-the-sky.org – at sunset Mercury's altitude is only 5 degrees (about the width of an extended fist).

To see the moon in conjunction one has to go further south; the conjunction won't be readily observable until one gets to latitudes of cities like Bogota, Colombia, where at sunset (5:38 p.m. local time) Mercury is 12 degrees high in the southwest; the planet won't be visible for at least another fifteen minutes, but by that time it is only 9 degrees high. In the Southern Hemisphere the situation improves slightly; from Melbourne, Australia, for example, the moon and Mercury are about 8 degrees high by 8:30 p.m. local time (sunset is at 8:08 p.m.) and they both set by 9:21 p.m.

Stars and constellations

November is when the winter constellations of the Northern Hemisphere become more prominent in the late evening and early morning hours; it's the time of year when Orion, Taurus and Gemini, to name three, are visible essentially all night long. By 8:00 p.m. in mid-northern latitudes in the northeast one can see Capella, the brightest star in Auriga the Charioteer, getting higher each day. Just south of Auriga (to the right of it earlier in the night) is Taurus, the bull, and from a dark sky location one can see the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters making a rough triangle with Capella and Aldebaran.

Above Auriga is Perseus, the legendary hero. By 9 p.m. Orion's belt is above the horizon and one can see the three stars – Alnilam, Alnitak, and Mintaka, going from east to west (when they are close to the horizon the line of stars appears almost vertical, with Alnilam at the bottom). An hour later Gemini has also risen fully above the eastern horizon, and at about 11 p.m. Canis Major, the Big Dog, which contains the brightest star in the sky, Sirius, is rising.

The Northern Hemisphere winter stars are a bright group; by 11 p.m. one can see several bright stars forming a rough ring around Betelgeuse, the right shoulder of Orion (as viewed from the ground). The bottom part of the ring would be Sirius, and if one looks to the left one sees another bright bluish white star, Procyon, which marks Canis Minor, the Little Dog. Further left and up is Pollux, the head (and namesake) of one of the Twins. Straight up from Pollux is Capella, and to the right of Capella and slightly downward is Aldebaran.

In the Southern Hemisphere, sky watchers will see the nights getting shorter – November is late spring there. In Melbourne the sky is fully dark by 10 p.m. on Nov. 13. In the east one can see the foot of Orion, Rigel, rising (constellations are "upside down" there) and to the right (southwards) one sees Sirius. In the southeast, about 27 degrees high, is Canopus, the brightest star in Carina, the Ship's Keel. Just west of south is Rigil Kentaurus, otherwise known as Alpha Centauri, only 13 degrees above the horizon. To the left is the Southern Cross, which is nearly set.

From just next to Rigel one can start tracing Eridanus the River, which winds across the southern skies towards the zenith, ending at Achernar, which is a full 65 degrees high in the southeast. If one looks to the right of Achernar one can see another bright star, Fomalhaut, which is the brightest star in the Southern Fish, Piscis Austrinus, which hugs the horizon in the Northern Hemisphere but can get quite high in the Southern, a full 73 degrees high.

If you want to get an up-close look at the stars or planets during the new moon or any other time, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you're looking to take photos of the moon or the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon or how to photograph planets, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.