60-Year-Old Aurora Comes to Life in Vintage Film and Drawings

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

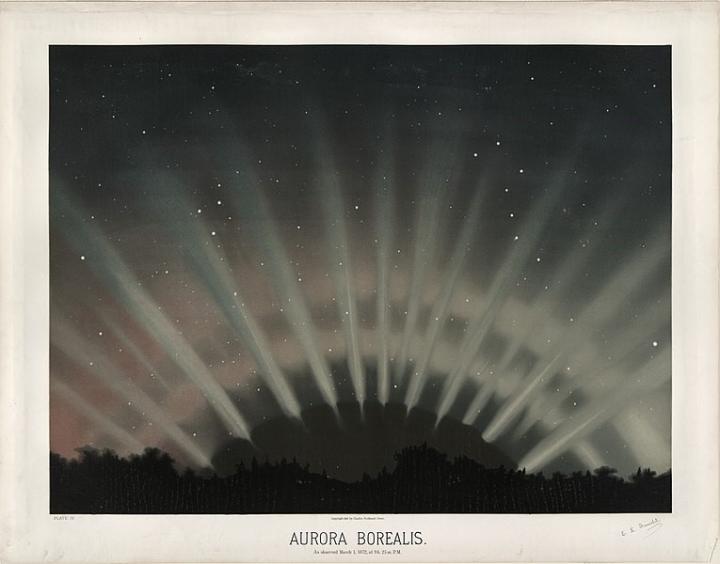

Six decades ago, a magnificent red splotch spread across the sky — and now, scientists think that by piecing together footage of the event, they better understand even older auroras.

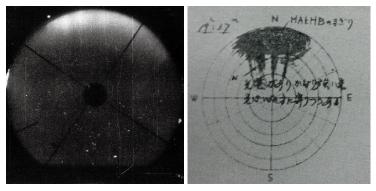

The researchers digitized microfilm observations of an aurora that danced over northern Japan on Feb 11, 1958. At the time, skywatchers also drew careful diagrams of the red, fan-shaped aurora, and by comparing the now-digital microfilm to the drawings, the researchers were able to better understand what was going on during this particular aurora, and during fan-shaped auroras in general.

"These phenomena are rare, but potentially disrupt [hu]man-made ground-based systems, including power grids," lead author Ryuho Kataoka, an associate professor at National Institute of Polar Research and the Graduate University for Advanced Studies (SOKENDAI) in Tokyo, said in a statement released by the institution. "If we understand such auroras, it may help mitigate the possible natural hazard they could produce."

Related: How to See the Northern Lights: 2019 Aurora Borealis Guide

The Feb. 11, 1958, aurora came during a particularly active period for the sun, one that saw an average of more than 350 sunspots per month, according to the new paper. With those sunspots came plenty of solar outbursts, and auroras over Japan were notable enough to make the newspapers seven times during the two years surrounding the event.

And on Feb. 11, observers at Memambetsu Magnetic Observatory in Hokkaido, were ready. They sketched and filmed and later described in writing the event, leaving the records that the team consulted in their new research. "It was like a mountain fire far away," an account written in Japanese describes the scene. "After 0930, pillars appeared alongside with the density change. Around 1000 UT, the color of the pillar was white, and it was like a searchlight from the ground; four pillars were recognized."

Those pillars don't show up in the now-digitized microfilm observations of the aurora. That's because camera eyes and human eyes see an aurora differently — and so by comparing the two media, scientists could piece together a more complete picture of what was happening in the sky. The microfilm, for example, better captured a greenish tinge that accompanied these bright white pillars of light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers also compared the observations with previous aurora events, particularly in 1770 and 1872. Although these events aren't recorded on microfilm, the scientists believe that they played out quite similarly to the 1958 event, based on drawings and written descriptions.

The team also offers a hypothesis to explain what precisely was happening in the sky during each of these auroras, as charged particles streaming off the sun collided with Earth's atmosphere. It's a crucial phenomenon to understand because when these particles hit satellites, rather than the atmosphere, they can interfere with our ability to communicate and navigate through those instruments.

The research is described in a paper published May 17 in the Journal of Space Weather and Space Climate.

- Northern Lights: What Causes the Aurora Borealis & Where to See It

- A 'Dragon Aurora' Appeared in the Sky Over Iceland, and NASA Is a Little Confused

- Amazing Auroras from 1989's Great Solar Storm

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.