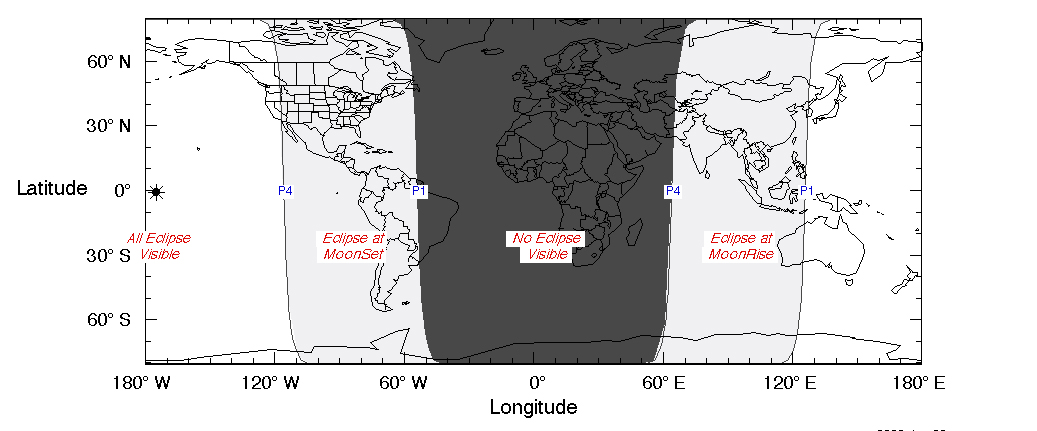

Earth's shadow will darken part of the moon Wednesday morning (March 23) in a lunar eclipse that will be visible from much of the globe, including central and western North America.

But don't get too excited, skywatchers. Wednesday's lunar eclipse is of the penumbral variety, and the effect will therefore be subtle and subdued compared to the jaw-dropping "blood moons" caused by total lunar eclipses.

Earth's shadow is composed of two parts: the dark, inner umbra and a faint, outer portion called the penumbra. As the term suggests, penumbral eclipses involve the moon dipping into the penumbra (but steering clear of the umbra). Weather permitting, well-placed observers who look carefully Wednesday morning should be able to see the moon's lower portions take on a smudged appearance. [How Lunar Eclipses Work (Infographic)]

The penumbral eclipse will last for 4 hours and 15 minutes Wednesday, but it may be noticeable for only a few minutes around 7:47 a.m. EDT (1147 GMT), the time of greatest eclipse, Space.com skywatching columnist Joe Rao wrote in our lunar eclipse guide last week.

People in central and western North America are in good position to witness greatest eclipse, but folks in the eastern parts of the continent will miss out; by that time, the moon will already have set from their perspective.

Observers throughout the Pacific Ocean region, New Zealand, Japan and eastern Australia will be able to see the entire penumbral eclipse, and skywatchers in eastern and central Asia will witness part of it. But Africa and Europe will be completely shut out, Rao wrote.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Lunar eclipsesoccur when the moon dives into Earth's shadow, during the satellite's full phase. But eclipses don't happen every month, because the moon's orbit around Earth is slightly out of plane with the planet's path around the sun.

When the moon, Earth and sun line up exactly right, a total lunar eclipse results. Partial and penumbral eclipses occur when the alignment is a little bit off.

The next two lunar eclipses — in September 2016 and February 2017 — will be of the penumbral type, and a partial eclipse will follow in August 2017. The next total lunar eclipse won't occur until January 2018. (The last one happened in September 2015.)

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing photo of the eclipse or any other night-sky sight that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send images and comments to Managing Editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.