Wild Sunspot Activity Looks Tamer in 400-Year Recount

Sunspots, the dark blemishes that speckle the surface of the sun, can appear and disappear daily, and scientists have been counting them for the last 400 years. Recently, a group of scientists revisited historical sunspot counts and came up with drastically lower numbers than previously reported, a finding that suggests the sun's activity has not varied as wildly as previously thought.

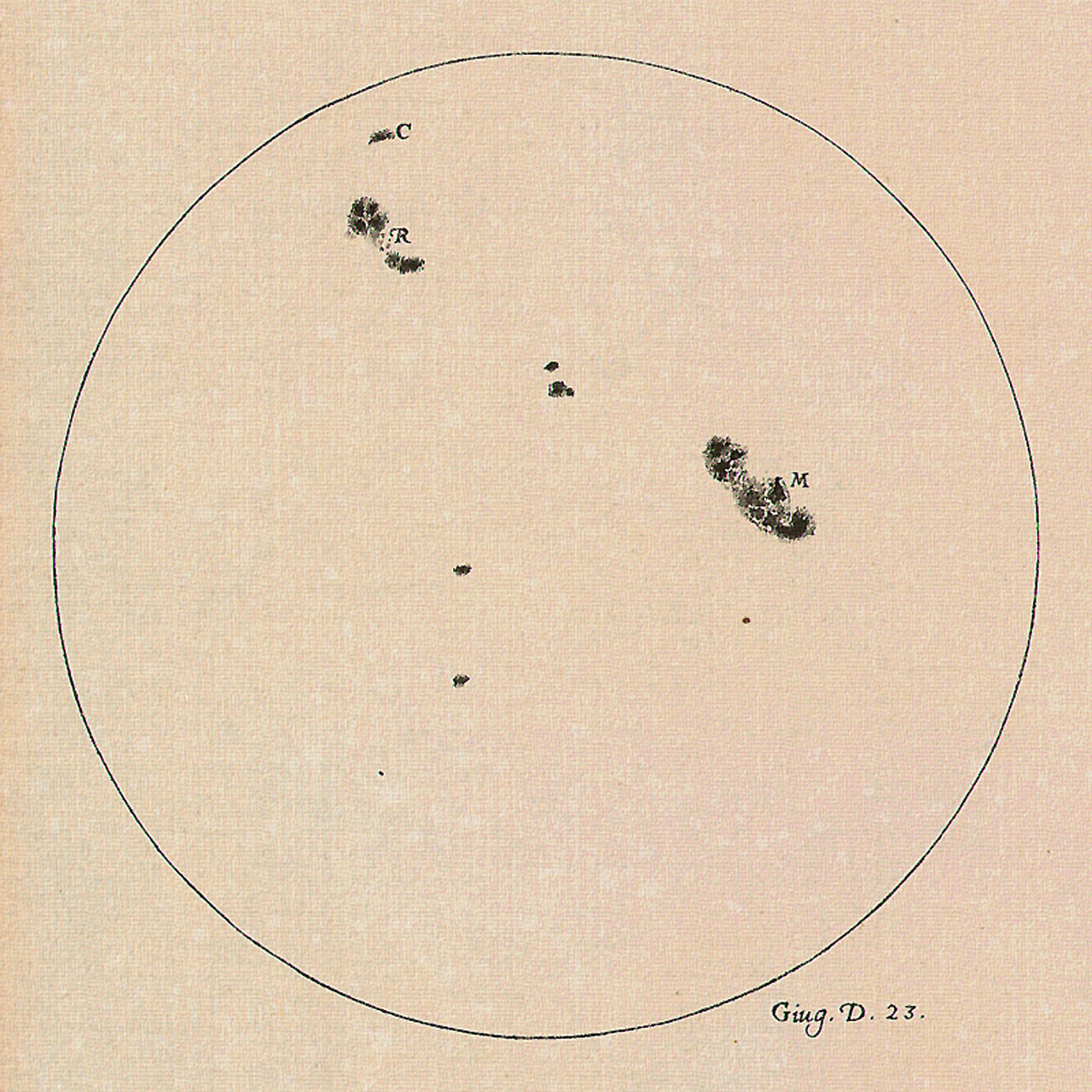

For over four centuries, both professional and amateur astronomers around the world have counted sunspots, even though it has only been in the last few decades that scientists have come to understand what causes these solar freckles. A project to keep track of daily sunspot numbers going all the way back to the early 1600s, called the Wolf Sunspot Number (WSN), is the longest still-running experiment in the world.

Counting sunspots on a given day seems like it should be a straightforward process, but scientists now say there were significant shortcomings in the methodology used in the WSN project. These scientists have done a complete historical recount that they are calling the Sunspot Number Version 2.0, which shows much more stable solar activity than was previously reported. The new results also suggest that increased solar activity is not directly responsible for recent rises in Earth's global temperature. [Photos: Sunspots on the Face of Earth's Closest Star]

Counting sunspots

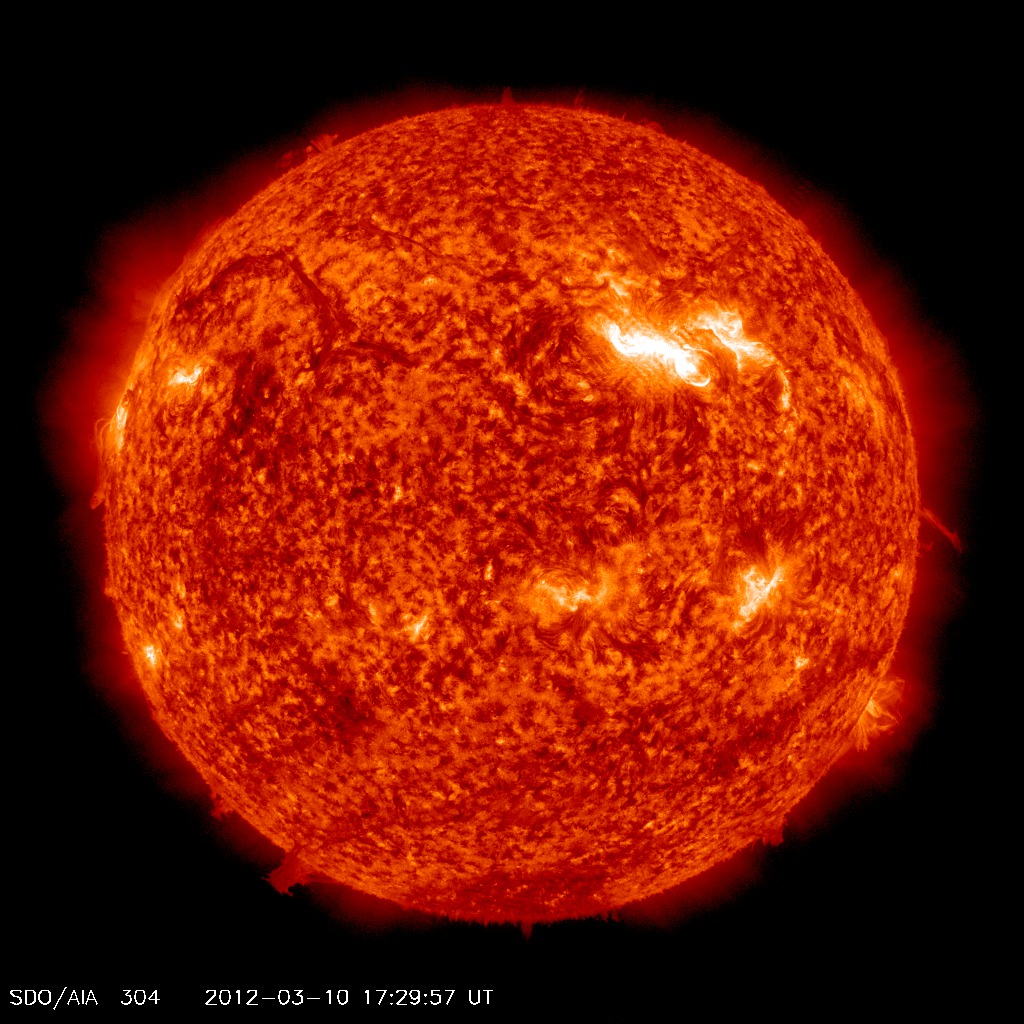

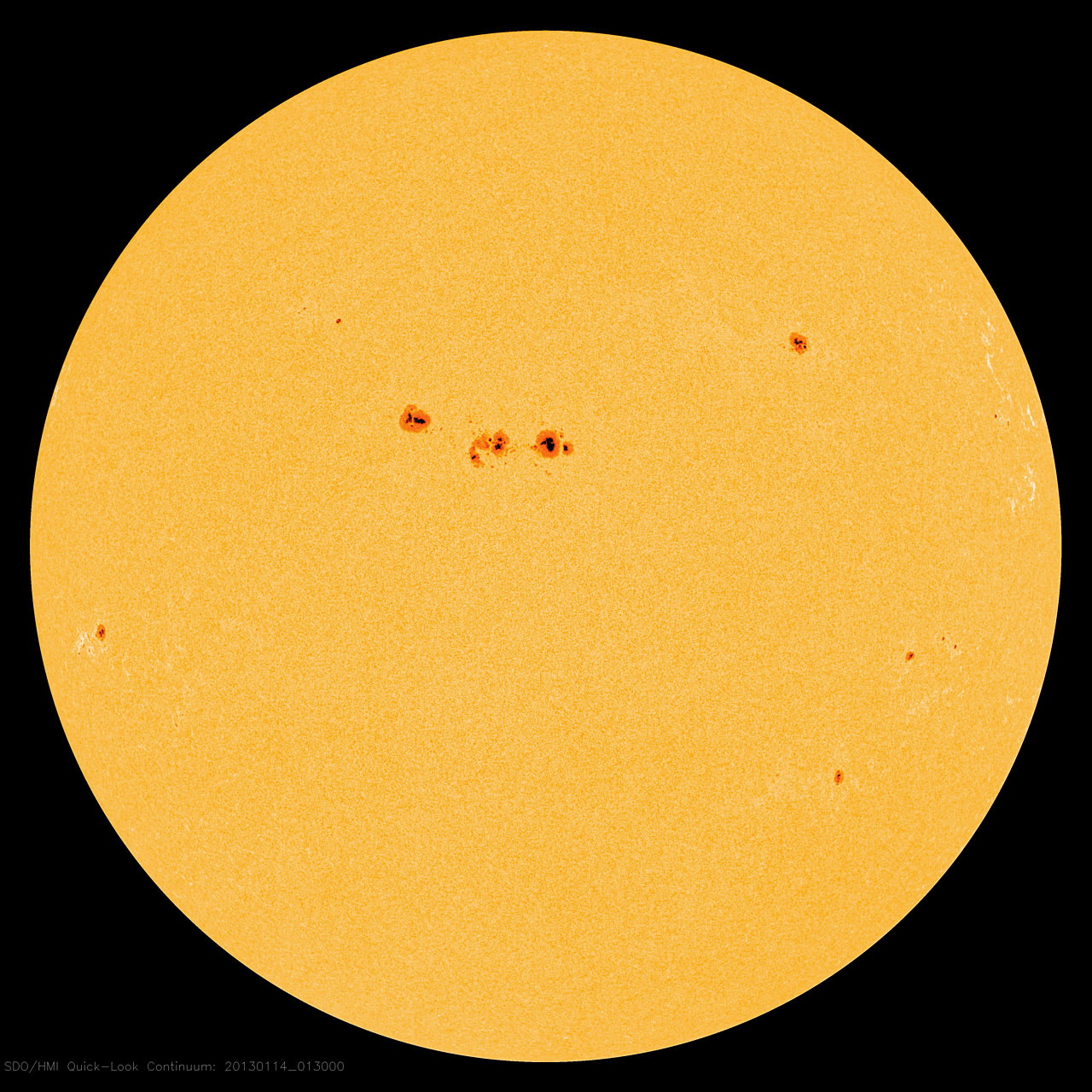

Images used by astronomers to count sunspots usually show the sun as a very smooth, yellow sphere, dotted with inky black splotches where the light is blocked out. (Warning: These images are created using special devices, and you should NEVER look directly at the sun.) How to Safely Observe the Sun (Infographic)]

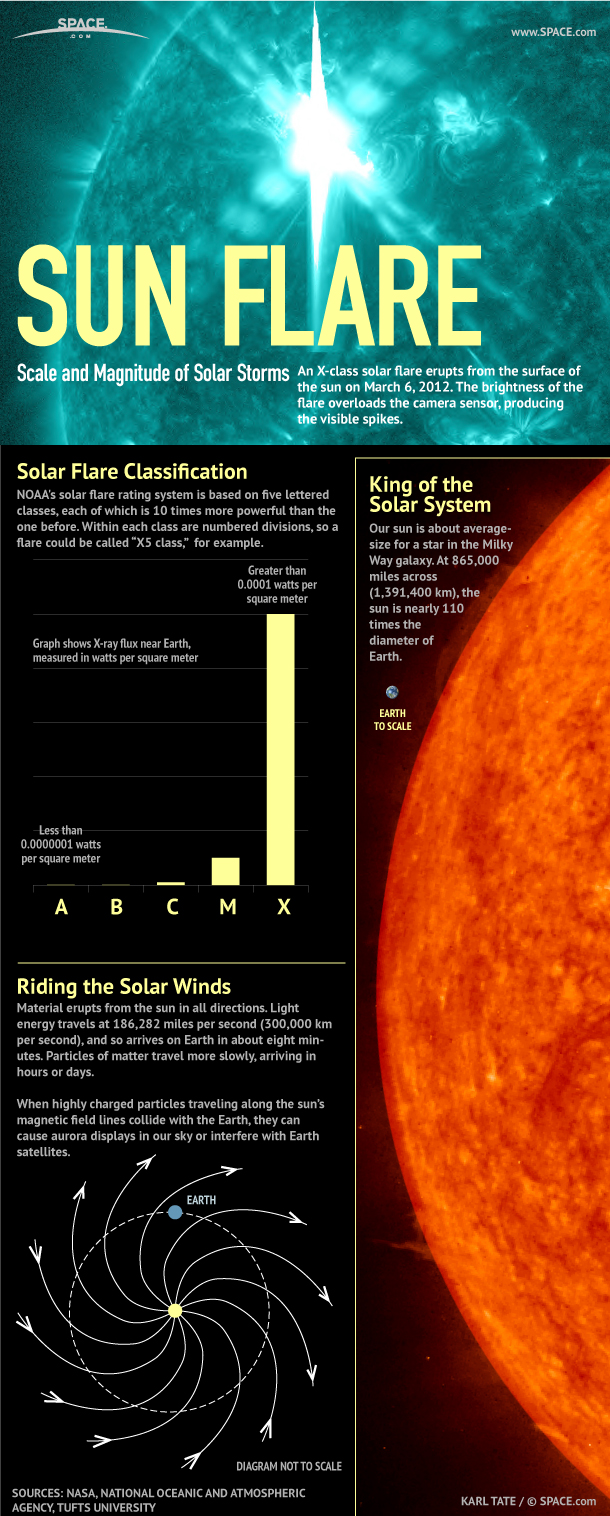

Scientists now know that sunspots are created by the sun's magnetic field, which loops and laces through the body of the sun like a gnarled ball of string. Sunspots sit on top of areas of strong magnetic activity, which can sometimes explode into solar flares or even coronal mass ejections, which spew hot, energetic particles into space (sometimes toward Earth). The number of sunspots can therefore tell scientists how magnetically active the sun was at any given time.

"In principle, [counting the number of sunspots] is very simple. You look at the sun, and you count the number of spots: one, two, three…" said Leif Svalgaard, a scientist at the Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory (HEPL) at Stanford University in California.

As it turns out, a number of variables can cause two observers to come up with different spot counts on the same day, including: the quality of the telescope or other observing apparatus used, geographic location, weather conditions, the vision quality of the observer, and personal opinion (such as when sunspots seem to blend together).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To find the true sunspot number (or get closer to it), scientists must account for those variables, said Svalgaard, who worked on the Sunspot Number Version 2.0 project. The project relied on historical records put down by astronomers going back to Galileo and his contemporaries. These sun studiers would either write down the number of sunspots, or record daily drawings of the sun's surface. The new project was led by Frédéric Clette, director of the World Data Centre [WDC]–SILSO.

Both Svalgaard and Clette spoke at a media briefing at the International Astronomical Union's General Assembly meeting in Honolulu, Hawaii, last Friday (Aug. 7). They explained that, in addition to better accounting for variables that affect sunspot counting, the new project incorporated some historical data missing from the WSN.

Possible flaws in the WSN were identified in the 1990s when a group of scientists generated the so-called Group Sunspot Number (GSN), which counted only sunspot groups (scientists now know that sunspots in the same "group" are linked magnetically, but historically these groups were just identified by how closely together they were clustered). The GSN produced vastly different numbers compared to the WSN for several periods in history. The discrepancies were "too prominent for the two systems to continue to exist in disagreement," according to a statement from IAU.

The results of the recount have been published in a series of papers, the first of which was released at the end of 2014.

Climate science

There is no doubt the sun's activity affects the Earth, but how it affects Earth's climate is an issue of intense debate, Clette and Svalgaard told Space.com.

Explosions of energy and material from the sun's surface can collide with the Earth and cause gorgeous auroras near the poles, but these collisions can also lead to electric surges in power grids. Scientists have shown that the sun's activity oscillates up and down in cycles lasting about 11 years. The sunspot data offers a unique opportunity for scientists to look back at more than 30 solar cycles, and search for patterns, Clette and Svalgaard said.

Based on the WSN, it appears that the sun's activity experienced a record low called the Maunder Minimum between 1645 and 1715, Clette explained during the media briefing. Sunspots were scarce during this time, and on Earth, global temperatures were also unusually cool. Some scientists took this as a sign that solar activity might be directly linked to, or even cause, temperature fluctuations on Earth.

"I think some people saw that and got that association in their heads," Svalgaard said.

In addition, the WSN showed a steady increase in sunspots over the last 300 years, with a peak in the late 20th century that has been "called the Modern Grand Maximum by some," according to the IAU statement. Some climate scientists took this as evidence that an increase in solar activity was driving the rise in Earth's temperature that has been observed after the Industrial Revolution, Clette said.

Clette and Svalgaard told Space.com that the results will demand a significant change in perspective by many climate scientists. In addition, the two researchers say the findings support an emerging view that while solar activity does fluctuate, it is not unbounded. That is, it goes up and down but stays between a steady maximum and minimum. Overall, the sun appears to be relatively stable, which means its effect on Earth's climate doesn't fluctuate wildly over time.

"Without that stability, we wouldn't be standing here talking about it," Clette said. "The stability allowed life to emerge on this planet."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter