Scientists Work to Protect Earth's Power Grids from Extreme Solar Storms

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Tools on the ground are helping scientists learn more about the threat solar eruptions on the sun pose to life as we know it on Earth.

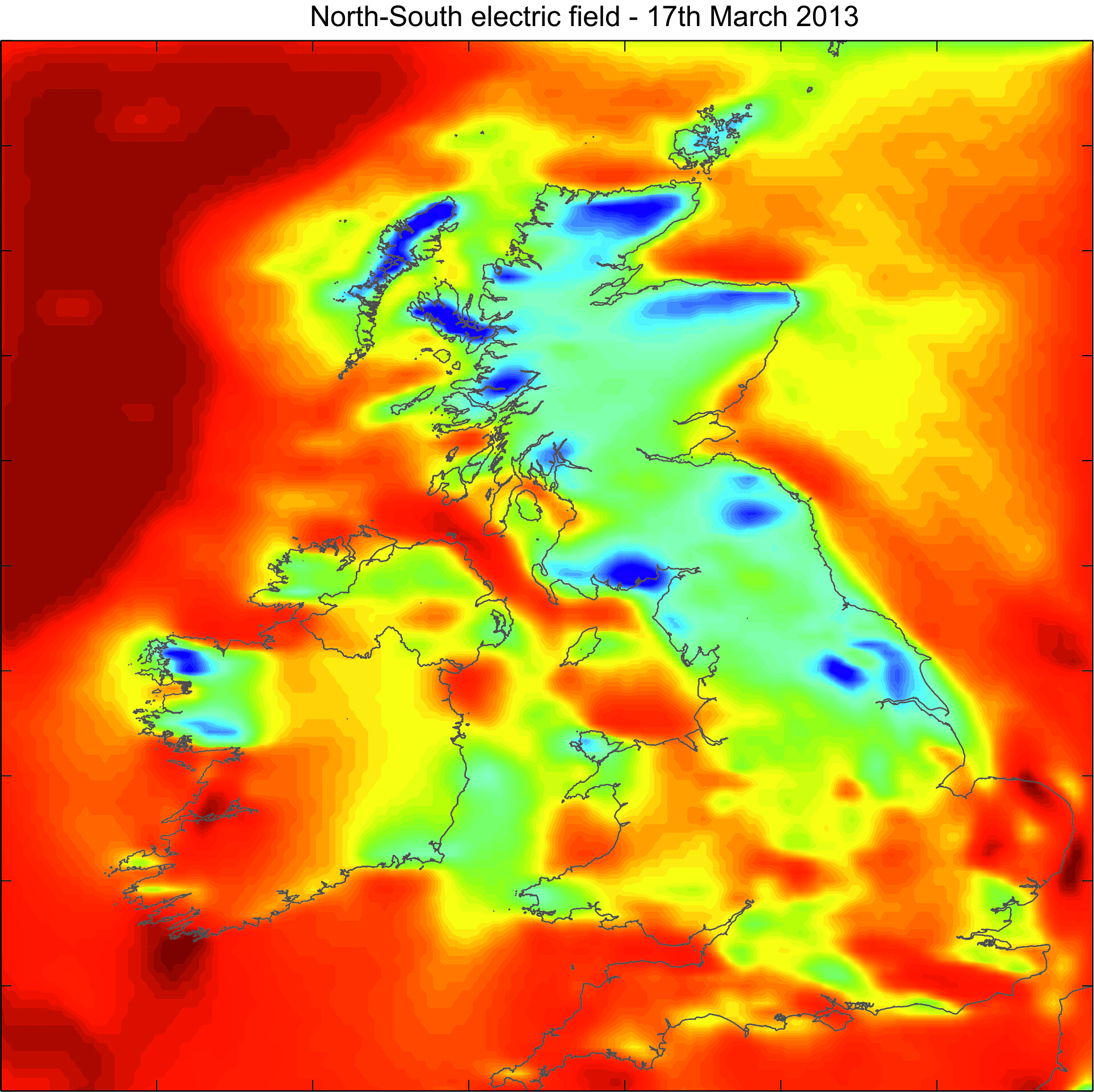

Experts with the British Geological Survey (BGS) have started collecting data from three research sites in the U.K. to determine the effects of massive solar storms on the Earth's electric power grids.

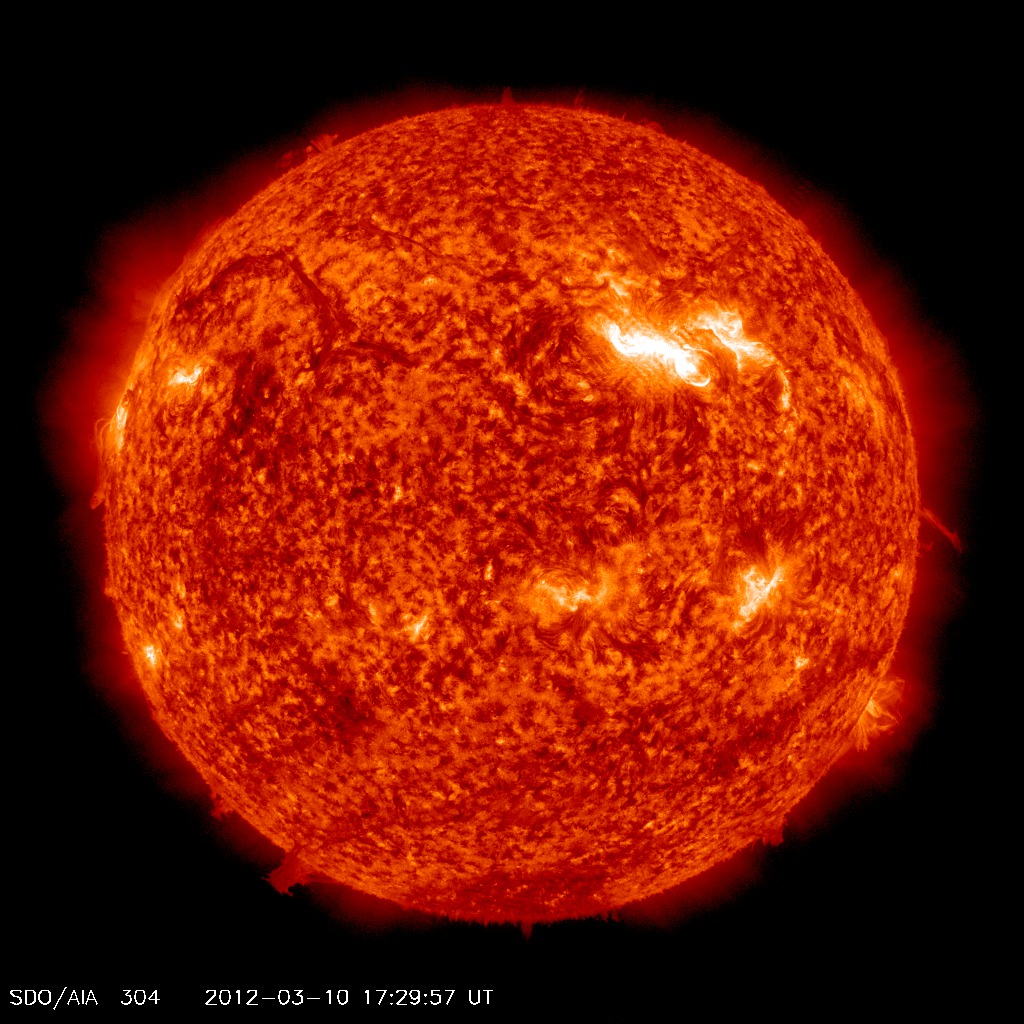

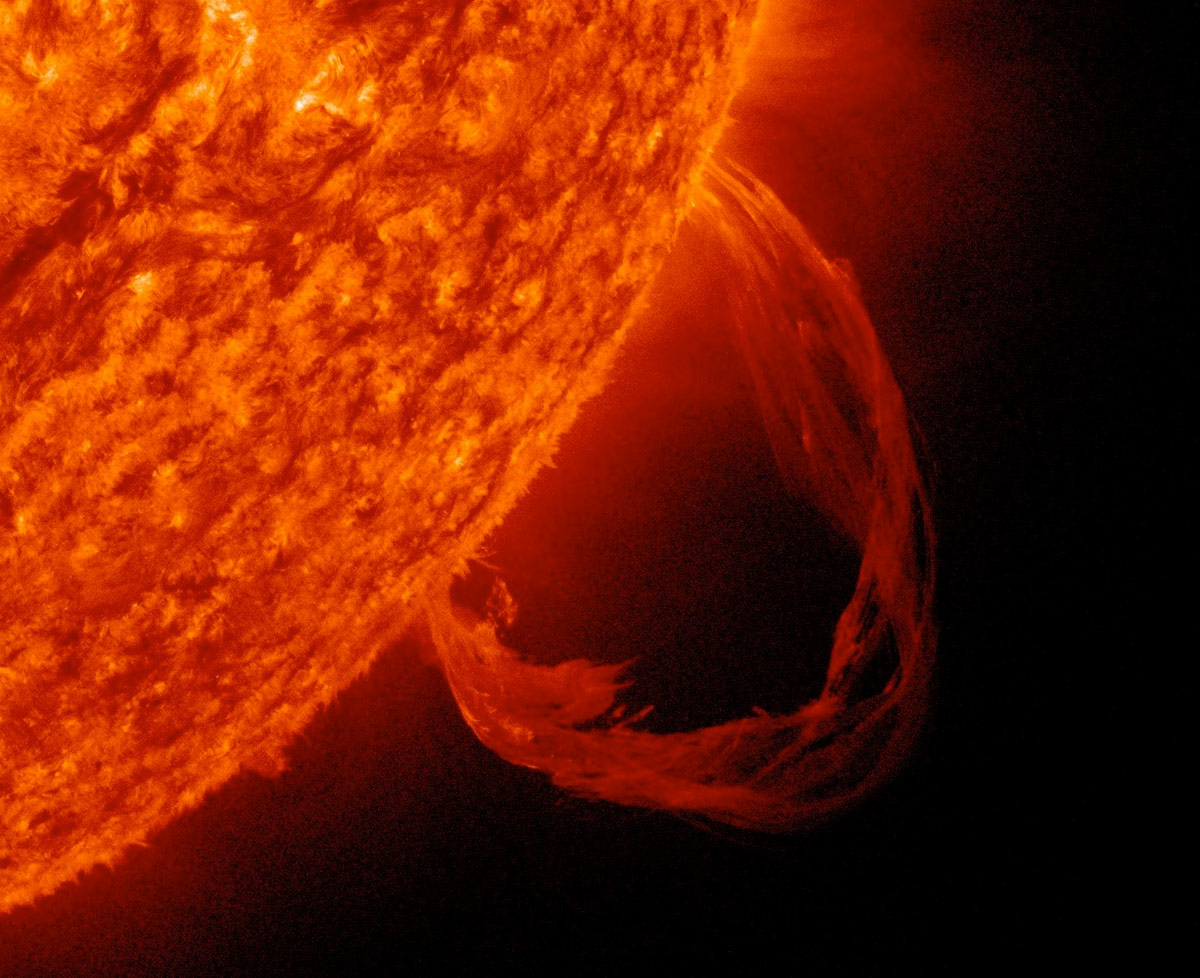

Although coronal mass ejections — giant sun eruptions of super-hot plasma that hurl charged particles across the solar system — are notoriously difficult to predict, scientists are trying to understand the best way to protect the power grid from an overload caused by extreme solar weather. [The Worst Solar Storms in History]

"Society depends on an intricate set of electrical and electronic systems, many of which are vulnerable to adverse space weather," BGS scientist Gemma Kelly said in a statement. "By measuring exactly what happens during a major storm event, we can work on better protection for our infrastructure and reduce the damage to the technology we rely on."

Kelly presented her work at the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting 2013 this week in the U.K.

There is always a small amount of natural electricity running through the ground. Under most circumstances, this electricity is harmless; however, a solar storm can exacerbate the currents underfoot, possible wreaking havoc on electrically linked systems around the world.

When solar storms hit the Earth in a certain way, it can disrupt the Earth's magnetic field, allowing strong electric currents in the upper atmosphere to induce currents on the ground, BGS officials said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The size of the electrical currents generated depends on a number of factors, such as the local bedrock type and the amount of water within the ground," BGS officials said in a statement. "The ground currents can become large enough to potentially cause problems to technology, such as high-voltage power grids, railway switches and long pipelines."

The three research sites set up at Shetland, the Scottish Borders and Devon in the U.K. will give Kelly and other researchers the first long-term continuous measurements of the ground current in the country, according to BGS officials.

"The electric field measurement system consists of sites of two pairs of electrodes, perpendicular to each other and spaced 100 meters apart," Kelly said in a statement. "Each electrode is buried one meter below the surface and the voltage is measured across each pair."

Kelly and her team will use the data collected during their survey to create better models that could help them better understand and predict the effects of solar weather.

Scientists estimate that an extreme solar storm only hits the Earth once every 100 years or so. The last documented severe solar storm that impacted the planet happened in 1859 and is known as the Carrington Event. Particles from a coronal mass ejection caused paper telegraphs to catch fire as the charged particles overloaded the wires.

A more minor solar event caused a large-scale blackout in Quebec, Canada in 1989. Six million people lost electricity for about 12 hours when a transformer was damaged because solar storm-bolstered ground currents overloaded the system, BGS officials said.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter and Google+. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.