What are lunar eclipses and how do they occur?

Lunar eclipses are a popular event for skywatchers worldwide.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Lunar eclipses occur when Earth moves between the sun and the moon, casting a shadow across the lunar surface.

Lunar eclipses can only take place during a full moon and are a popular event for skywatchers around the world, as they can be enjoyed without any special equipment, unlike solar eclipses.

The next lunar eclipse will be a partial lunar eclipse on Aug. 27-28.

Article continues belowRelated: Night sky guide, what you can see tonight

What are lunar eclipses?

A lunar eclipse is caused by Earth blocking sunlight from reaching the moon and creating a shadow across the lunar surface.

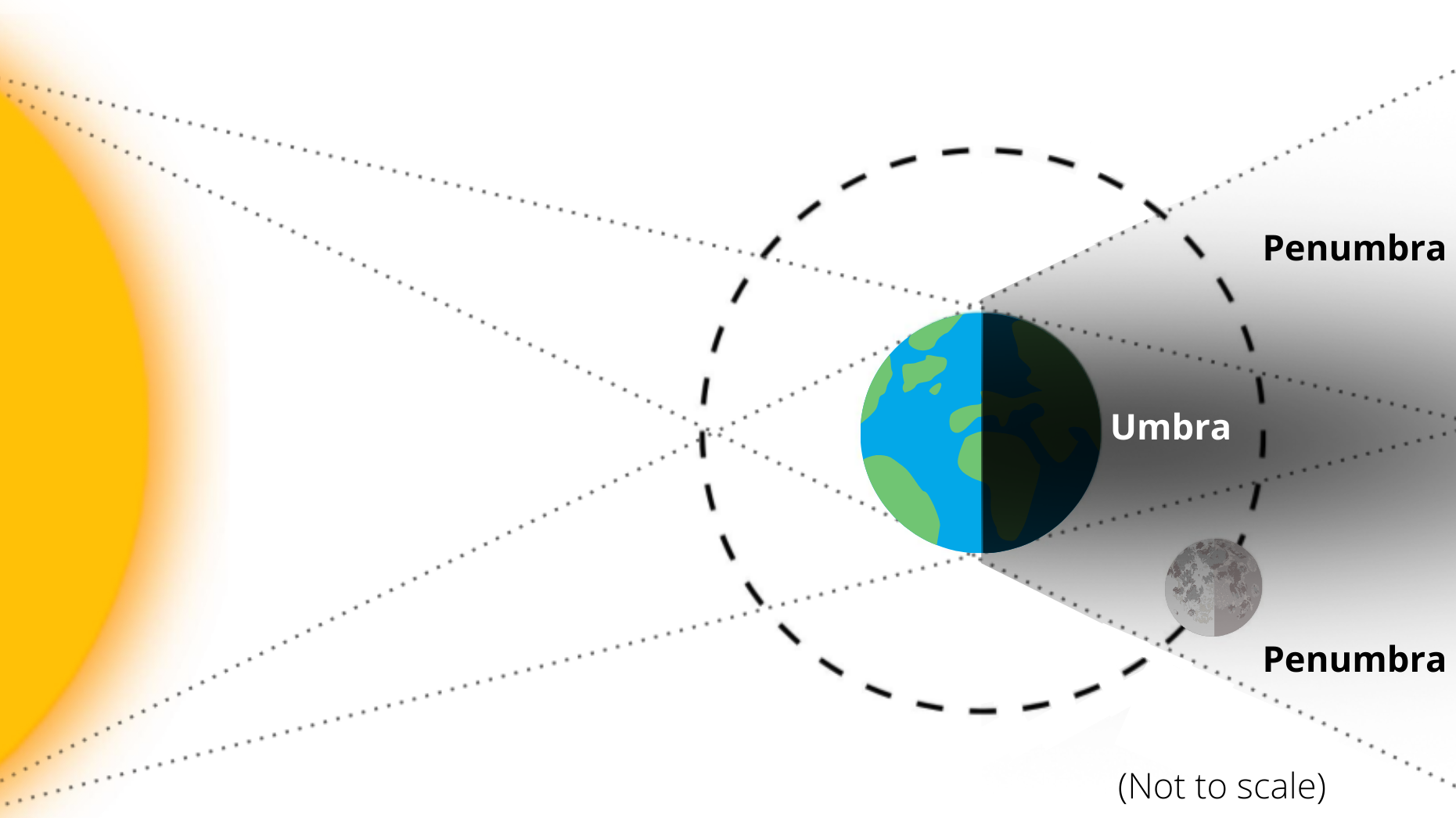

The sun-blocking Earth casts two shadows that fall on the moon during a lunar eclipse: The umbra is a full, dark shadow, and the penumbra is a partial outer shadow.

There are three types of lunar eclipses depending on how the sun, Earth and moon are aligned at the time of the event.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- Total lunar eclipse: Earth's shadow is cast across the entire lunar surface.

- Partial lunar eclipse: During a partial lunar eclipse, only part of the moon enters Earth's shadow, which may look like it is taking a "bite" out of the lunar surface. Earth's shadow will appear dark on the side of the moon facing Earth. How much of a "bite" we see depends on how the sun, Earth and moon align, according to NASA.

- Penumbral lunar eclipse: The faint outer part of Earth's shadow is cast across the lunar surface. This type of eclipse is not as dramatic as the other two and can be difficult to see.

What happens during a lunar eclipse?

Why does the moon turn red during an eclipse?

During a total lunar eclipse, the lunar surface turns a rusty red color, earning the nickname "blood moon". The eerie red appearance is caused by sunlight interacting with Earth's atmosphere.

When sunlight reaches Earth, our atmosphere scatters and filters different wavelengths. Shorter wavelengths such as blue light are scattered outward, while longer wavelengths like red are bent — or refracted — into Earth's umbra, according to the Natural History Museum. When the moon passes through Earth's umbra during a total lunar eclipse, the red light reflects off the lunar surface, giving the moon its blood-red appearance.

"How gold, orange, or red the moon appears during a total lunar eclipse depends on how much dust, water, and other particles are in Earth's atmosphere" according to NASA scientists. Other atmospheric factors such as temperature and humidity also affect the moon's appearance during a lunar eclipse.

How often do lunar eclipses happen and how long do they last?

In astronomical terms, a lunar eclipse is a relatively common phenomenon, with about three lunar eclipses occurring every year, according to the National History Museum. Approximately 29% of lunar eclipses are total lunar eclipses, according to TimeandDate.com.

A solar eclipse always occurs about two weeks before or after a lunar eclipse.

A total eclipse can be seen from any given location — on average — once every 2.5 years.

A lunar eclipse usually lasts a few hours, according to the National Weather Service, with totality (the duration of total obscuration of the moon) ranging between 30 minutes to over an hour.

Lunar eclipses are more easily observed than solar eclipses, as they can be viewed with the unaided eye by any observer situated where the moon is above the horizon (Reminder: Never look directly at the sun, even during a total solar eclipse, without protection such as verified eclipse glasses; serious and permanent eye damage can result.)

How to see a lunar eclipse

Looking for a telescope for a lunar eclipse? We recommend the Celestron StarSense Explorer DX 130AZ as the top pick for basic astrophotography in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Lunar eclipses are among the easiest skywatching events to observe.

To watch one, you simply go out, look up and enjoy. You don't need a telescope or any other special equipment. However, binoculars or a small telescope will bring out details on the lunar surface — moonwatching is as interesting during an eclipse as it is at any other time.

If the eclipse occurs during winter, bundle up if you plan to be out for the duration — an eclipse can take a couple of hours to unfold. Bring warm drinks and blankets or chairs for comfort.

Scientists like to watch lunar eclipses, too.

"We can get really good science out of what happens to the surface of the moon during total lunar eclipses, but again, the cool thing is that the moon changes color," Noah Petro, a research scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, told Space.com. "It's something fun to see — it's benign, but it's a change. And anytime we see [a] change in the skies, it's always kind of exciting."

If you hope to snap a photo of a lunar eclipse, here's our guide on How to photograph a lunar eclipse with a camera. And if you need imaging equipment, our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography have recommendations to make sure you're ready for the next eclipse.

Lunar eclipse FAQs answered by an expert

We asked meteorologist and Space.com skywatching columnist Joe Rao a few commonly asked questions about lunar eclipses.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium.

What is a total lunar eclipse?

When the moon moves completely into the Earth's dark shadow cone (called the "umbra") we call that a total lunar eclipse. At the moon's average distance from Earth of 239,000 miles [383,000 km], the umbra measures roughly 5,800 miles [9,334 km] in diameter. The moon is about 2,200 miles [3,540 km] in diameter. So there's no problem in getting the moon completely immersed in the umbra; there's plenty of room.

Why do lunar eclipses occur?

Lunar eclipses can only happen when the moon is directly opposite to the sun in our Earthly sky at the time of the full moon. But we don't get a lunar eclipse every month — that is, at every full moon. The reason for this is simple: the moon's orbit is inclined to the Earth's orbit by just over 5 degrees. So more often than not, the full moon will pass either above or below the Earth's shadow. However, there are times when the sun, Earth and moon are aligned in such a way that the moon will pass either partially or totally into Earth's shadow, producing a lunar eclipse.

What's the difference between a lunar eclipse and a solar eclipse?

A solar eclipse occurs when the moon crosses in front of the sun (at new moon). A lunar eclipse is something quite different. It occurs when the full moon passes into the Earth's shadow.

Additional resources

Learn more about lunar phases and eclipses with NASA Science. Explore Hanwell Community Observatory's fact sheet for more lunar eclipse information. Discover why we don't have a lunar eclipse every month with the Rice Space Institute at Rice University.

Bibliography

NASA. Blood Red Moon: Total Lunar Eclipse. NASA. Retrieved May 10, 2022,

O'Callaghan, J. (2019, July 16). Lunar eclipse guide: What they are, when to see them and where. Natural History Museum. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

NASA. (2017, May 3). What is an Eclipse? NASA. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

Hocken, V., Kher, A. Total Lunar Eclipse. timeanddate.com. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!

- Robert Roy BrittChief Content Officer, Purch

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.