Executioner's Song: Deciding Which Space Missions Live or Die

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

UPDATE: Story firstposted 7:15 a.m.

There has been a scientificand public backlash at the thought of shutting down spacecraft, like thevintage Voyager missions, all for the want of a few millions dollars.

But Voyager is likely to be anearly signal from a growing dilemma of finding cash to keep NASA spacecraftfunctioning beyond their initial work period.

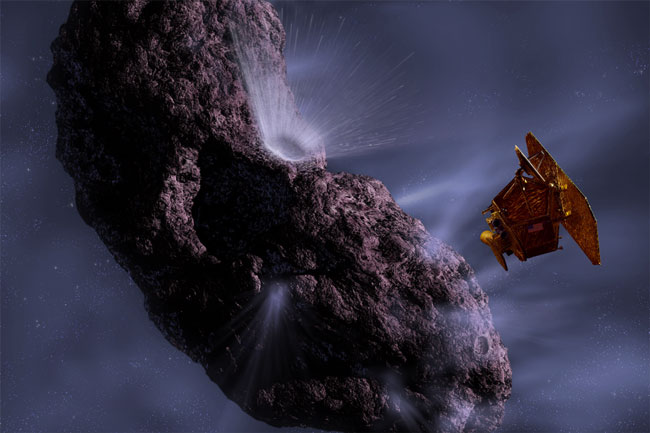

There are plenty ofexamples, like the still-going strong Mars Exploration Rovers. Also count onkeeping the Hubble Space Telescope alive. Toss in an extended Cassini mission at Saturn too. Also, there's early talkabout the Deep Impact flyby spacecraft possibly using its telescopic gear toscout about after it completes its main choir of hurling an impactorat comet Tempel 1 and monitoring the upshot thiscoming July.

But now there is growingtalk of setting up something analogous to a "hit squad" at NASA thatimpartially agrees what projects should be ended, when, and under what rules.

Reportedly, a number ofspace probes could be on the chopping block, from the Ulysses mission to theSun to several Earth-oriented space physics satellites busily sleuthing about.

Upsetting to many scientistsis shutting down the long-distance Voyager -- seemingly a fit of heliospheric heresy. The valiant twin Voyager spacecraftwere launched in 1977 and can define the end of the heliosphere-- the entire region of space affected by the Sun -- and the start ofinterstellar space.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The mission currentlyemploys the equivalent of about 10 full-time people at the Jet PropulsionLaboratory, significantly less than the approximately 300 during the height ofits legendary "Grand Tour" of the planets through 1989.

Scientific novelty

New NASA Administrator, MikeGriffin, will likely revisit a number of "pulling the plug"decisions, suggested Stamatios Krimigis,Head Emeritus of the Space Department at the Johns Hopkins University AppliedPhysics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

"It's clear that in alimited resource environment, decisions and choices have to be made...none wouldargue with that," Krimigis said. "The keyissue is the criteria used to arrive at such decisions."

Speaking at the pressconference Monday following his appointment, Griffin said NASA was months away decidingwhich missions get terminated, and that it "would not be done without a fulland careful review."

But, he added, that is not"to say that all missions are of the same importance. Voyager may well outrankothers whose time to be turned off really has come. So I'm not making a blanketoffer that we're going to reach a particular answer on any one mission or thatwe will treat them all as a block. But we are going to consider it carefullybefore we turn anything off."

Principal among the criteriawould be the scientific productivity of a particular mission, Krimigis said.

"This is the area wherethe Voyager decision is totally indefensible. Why? Because Voyager has been atthe fringes of the solar 'cocoon' that separates us from interstellar space fornearly three years now," Krimigis explained.Voyager has generated impressive science for so many years, and the excitementhasn't stopped, he observed.

As a principal investigatoron Voyagers 1 and 2, Krimigis also serves in thatrole on the Cassini mission now orbiting Saturn.

The scientific novelty ofthis region of space is clearly intriguing not only for scientists but thepublic at large, Krimigis argued.

Exploration at its finest

Voyager is "explorationat its finest," Krimigis said. "NASA has nopresent plans for an Interstellar Probe, and even if they approved such amission tomorrow it couldn't launch until 2014 and wouldn't catch up withVoyager for at least 15 years after that," Krimigisnoted. Voyager is likely to run low on power by about 2020, he said, but couldpossibly continue in some reduced capacity for several years after that, doingso through power sharing and other procedures.

"It's a legacy missionthat this generation can preserve for our children and evengrandchildren," Krimigis stated. NASA pondering apull-the-plug dictum on Voyager, he continued, is a decision without thoughtabout the mission's current scientific productivity or appeal of the science tothe public.

"After all, $4 millionis $4 million...and to accountants all funds are the same. No wonder thescientific community has so little confidence in the decision-making at [NASA]Headquarters," Krimigis said.

Of course, not all extendedmissions hold the excitement of the Voyagers, but all of the ones scheduled fortermination next year are scientifically productive, Krimigissaid.

"I believe the returnon investment for all is very high," he said, and there is no way NASAcould reconstitute these assets in the next 20 years. They are the equivalentof a "Great Observatory" and must be recognized as such, Krimigis concluded.

NASA's extended family

NASA has several spacecraftthey embrace as part of their "extended family".

Mars has become home to theextended orbital missions of Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Odyssey.Furthermore, those workaholic surface robots, Spirit and Opportunity,just got the go-ahead for up to 18 more months of operations - purportedly atroughly $3 million per month.

The peppy twin Mars rovershave been a surprise to engineers and scientists. They had already completed 11months of extensions on top of their successful three-month prime missions. Andwhat does another 18 months buy?

Pose that question to Steve Squyres of Cornell University as leader ofthe Mars rover science team. He's quick to answer about the value of theirrecently renewed Mars driving license.

"The thing that makesit so valuable is that we keep moving across the Martian countryside. If you'restuck in one place, sooner or later your science becomes nothing but routinemonitoring of time-varying phenomena... like studying the atmosphere. That'simportant science, but it wouldn't use the rovers to anything like their fullcapability," Squyres told SPACE.com.

By keeping the rovers on themove, new places are always just around the bend, beyond a crater wall, orbehind a sand dune.

"One thing that we'velearned consistently on this mission is that our landing sites are so complexand interesting that when we go to a new place...we see new science," Squyres confirmed.

The surface of Mars is a bigplace. It takes a little driving around to find things, said David DesMarais of NASA's Ames Research Center. He is leadscientist of the long-term planning team in NASA's Mars Exploration Rover (MER)mission.

"The longer the missiongoes, the smarter we get about Mars geology," DesMaraissaid. "The longer we live...we're doing a better job."

Searching for nickels everywhere

Long-lived spacecraft thatreceive mission extensions usually cost less to operate than during their primetime.

However, they should be madeto run cheaper too, which is not always the case, said Wesley Huntress, Jr.,Director of the Geophysical Laboratory at the Carnegie Institution ofWashington in Washington, D.C. In a former post, he served as thechief of NASA's space science missions.

Space is populated with alarge collection of older spacecraft still cranking out data, Huntress said.That being the case, the accumulative cost of running them begins to becomesignificant, he said.

And that's what is happeningnow, with NASA "searching for nickels everywhere," Huntress stated.Budget pressure is omnipresent.

"It's a limitedresource. You want to do new things, but you have some old things that arestill productive. How do you make that tradeoff? The advocates of thesemissions don't have to worry about that...the folks who are writing the checksdo," Huntress advised. "And so you see that battle happening."

Precipitous decisions

Huntress said he worriesthat NASA at its upper levels has lost the understanding that they havestakeholders. "They can't make precipitous decisions without consultationwith their stakeholders. The idea of canceling Voyager, for example, seems illconceived ...it seems to me to make very little sense," he said.

Similar in view is SeanSolomon, Director Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the CarnegieInstitution of Washington. He is principal investigator for the now en route MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment,GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) mission.

"One of the reasonsthat the Voyager discussion is so intense is because there is a potential fornew science...even though this mission has been on the books now for more than 30years," Solomon remarked. While NASA has many demands on its resources,the price tag to follow Voyager a little longer is not that great.

"On the other hand,there are many missions that are contemplating extended periods. So youprobably can't do them all," Solomon pointed out. "The question ishow do you decide which are the most worthy of these missions to continue toinvest in?"

There are gauges for makingsuch a determination: Health of the spacecraft's instruments; remaining fuelonboard to maintain attitude and pointing accuracy; and the originality and importanceof the scientific return.

"But at some point NASAis deciding between extending a mission and flying a new mission. And that's atougher call," Solomon said. "There is a natural tendency for activescientific groups to continue to want to see data coming in. So that's why anyprocess of deciding on how to invest scarce dollars in extended missions shouldbe an objective one...one in which a broader community is looking at comparisonsamong different kinds of missions with different kinds of objectives," heconcluded.

Report card: far from stellar

The debate over the HubbleSpace Telescope's longevity is a hard call, Huntress said. Essentially, boththe Hubble and its follow-on, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are on more or less a fixed budget.

"So the money spent onHubble you're not going to spend on JWST. When do you make that call? That's atough judgment," Huntress said. "And it's tougher in the case ofHubble because it is not just a telescope for scientists anymore. It has becomethe people's telescope."

Try turning off one of theMars rovers today, Huntress said. "You'd get the same reaction that you'regetting from Hubble. So I don't think it's peculiar to Hubble. I think it'speculiar to the way the American public takes ownership of theseinstruments," he noted.

During his tenure at NASA,Huntress had to put to rest the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory. Compton was safely deorbitedand reentered the Earth's atmosphere on June 4, 2000.

"That one had no publicconsequences. That was strictly an engineering and scientific decision,"he said, with gamma ray astronomers knowing that American and Europeanfollow-on missions were coming. "Compton'stime had come."

Overall, NASA's report cardon turning off spacecraft is far from stellar, Huntress admitted. "I thinkNASA prepares poorly, if at all, for extended missions...and that includes mytenure there too. We did not plan well for extended missions because we neveranticipated them. But we always knew there was the potential for them," hesaid.

Striking the right balance

"It's something I'mwrestling with," said NASA's Alphonso Diaz,NASA's Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate."Somebody's extended mission is another person's prime mission," hetold SPACE.com.

Diaz said that a seniorreview process done a few years ago to rank the strategic importance ofmissions "may or may not be relevant to the discussion today." NASAis presently engaged in strategic road-mapping, he said, with some missionsperhaps having more significance now given the space agency's Moon, Mars, andbeyond visionary agenda.

"I'm willing tolisten...to sit down and talk about that," Diaz said. "We're currentlydeveloping a strategy to try and understand how to get to another review, onethat's based on more current understanding of the significance of thosemissions," he said.

Reducing the cost ofoperating some spacecraft over a long period is on the table too, Diazexplained. Coming up with the right balance of continuing to operate extended missionsversus new developments is the trade that has to be made, he said.

"It'll be a whilebefore we have a solution," Diaz added. "We can't operate everythingall the time forever."

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.