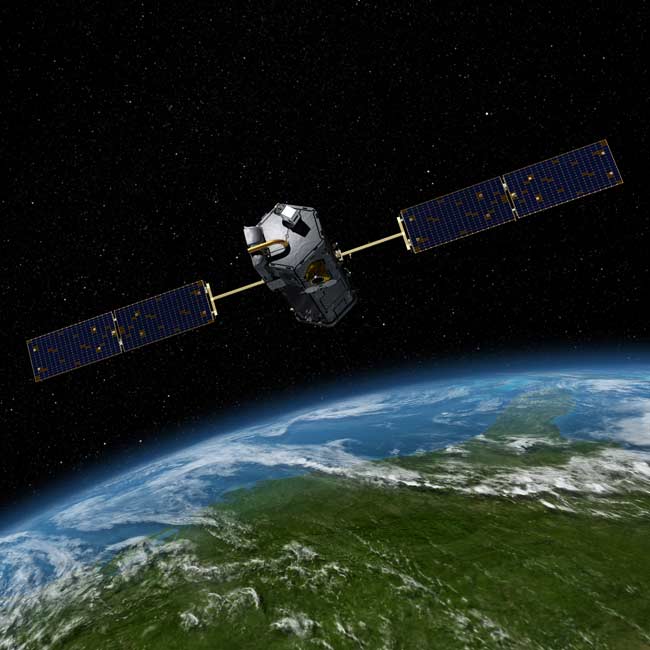

New NASA Carbon Probe to Help Track Climate Change

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

SANFRANCISCO ? As NASA?s new Orbiting CarbonObservatory (OCO) moves closer to its planned launch next week, the teamresponsible for the spacecraft faces enormous challenges to fly the first-everprobe to map carbon dioxide levels across.

?OCO will be making one of the mostchallenging measurements of any atmospheric trace gas that has ever been made,?said Charles Miller, OCO deputy principle investigator at the Jet PropulsionLaboratory (JPL), in Pasadena Calif.

OCO ispoised to launch from California?s Vandenberg Air Force Base atop a Taurus XLrocket on Feb. 24 to begin its carbondioxide-hunting mission. The spacecraft will use three high-resolutionspectrometers built by Hamilton Sundstrand Sensor Systems of Pomona, Calif., tomeasure carbon dioxide and oxygen molecules in the Earth?s atmosphere based onthe way those molecules absorb sunlight.

That datawill then be used to show the specific regions where natural and man-madesources are producing carbon dioxide as well as highlighting areas, calledsinks, where oceans and plants are removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.OCO will circle the Earth every 99 minutes, mapping the globe every 16 daysfrom its near-polar, sun-synchronous orbit.

HuntingEarth?s carbon

Throughvarious activities including forest fires and the burning of fossil fuels,sources on Earth emit approximately 8 billion tons of carbon every year. But onlyhalf of that carbon remains in the atmosphere. The other half is hidden - absorbedby Earth?s oceans, plants and soils, said Anna Michalak, OCO science teammember from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

?Therelative fraction of carbon that is staying in the atmosphere versus going intoplants and oceans varies dramatically from year to year,? Michalak said. ?Wewant to understand why plants and oceans are taking up as much carbon as theyare ... so we can predict how they will behave in the future.?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once thespacecraft is in orbit, the OCO management team will spend up to 13 weeksconfirming that the spacecraft and its subsystems are functioning properly,said Ralph Oscillo, OCO deputy project manager at JPL. Once OCO is found to bein good working order, the spacecraft will be maneuvered into position as thelead spacecraft in the A-Train, a constellation of fiveEarth observing satellites flying in formation around the globe.After that, OCO scientists will spend months evaluating the initial data beingreturned by the onboard instrument to ensure the spectrometers are fullycalibrated. Oscillo said science operations would begin in October or Novemberwhen the OCO team plans to begin providing data showing the regionaldistribution of carbon dioxide.

Bigchallenges in tiny changes

Theenormous challenges inherent in the mission are due to the small variations inthe amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Those levels range from a maximum of362 carbon dioxide molecules in 1 million molecules of air, to a minimum of 351carbon dioxide molecules in 1 million air molecules - a 0.3 percent difference,said David Crisp, principle investigator for the OCO at JPL.

Thevariation, while small, has big implications for scientists studyingclimate change. For OCO to do its job, it must accurately measure theminuscule changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

To verify that OCO?s measurements of atmosphericcarbon dioxide concentrations are accurate, data gathered from the spacecraftwill be compared with measurements obtained by ground stations, tall towers andairborne instruments as part of the National Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration?s carbon dioxide research program, Michalak said.

OCOinstrument data also will be compared with observations made by Japan AerospaceExploration Agency?s Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite - or GOSAT - whichwas renamed Ibuki followingits Jan. 23 launch. Ibuki is designed to measure carbon dioxide levelsaround the world. However, the two spacecraft carry very different instruments.Ibuki carries an interferometer designed to detect atmospheric methane andcarbon dioxide. OCO employs a gradient spectrometer designed specifically tomeasure carbon dioxide, Crisp said.

?Theobjectives of the two missions are different,? Crisp said. ?GOSAT [Ibuki] islooking for carbon dioxide sources for treaty monitoring purposes. Thosesources are a little easier to see than sinks, because sources are fairlyintense and localized. We are looking for sinks which are much weaker, moredistributed and harder to find.?

The twosatellites will cross orbit paths several times a day. ?That gives us anopportunity to take nearly simultaneous measurements at a few points on theglobe every day so the teams can compare the results,? Crisp said.

The NASAbudget includes $278 million for the entire OCO mission, which is scheduled tolast two years. If the primary mission is successful, NASA officials couldextend OCO?s science operations well beyond 2011. The spacecraft carries enoughfuel to remain in orbit for five to 10 years, Crisp said.

- New Video - NASA?s Orbiting Carbon Observatory to Track Climate Change

- Video - Goldilocks, Science and Climate Change

- Video - Antarctic Ice Shelf Disintegrates

Debra Werner is a correspondent for SpaceNews based in San Francisco. She earned a bachelor’s degree in communications from the University of California, Berkeley, and a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University. Debra is a recipient of the 1989 Gerald Ford Prize for Distinguished Reporting on National Defense. Her SN Commercial Drive newsletter is sent out on Wednesdays.