Recent CubeSat Losses Spur Renewed Development

LOGAN, Utah - It was a darkday for CubeSat builders. The seventh launch of the Dnepr launch vehicle hauling overa dozen spacecraft blasted upward into the night from its silo site at theBaikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan.

Butsome 73 seconds after launch, the converted Cold War SS-18 missile ran intotrouble. The booster and its cargo of satellites crashed down range, plowinginto an unpopulated desert area.

The accident meant the loss of 18 satellites, including the first spacecraft of Belarus--a remote sensing craft called BelKA--along with a Russian Baumanets satellite developed by the students of Bauman State Technical University. Also onboard, several smaller satellites: UniSat-4 and PiCPoT from Italy, and five "P-Pod" containers collectively loaded with 14 CubeSat satellites from 10 different universities around the globe and the U.S.-based The Aerospace Corporation, a private company.

It was billed as the largest deployment into Earth orbit of CubeSats ever--a milestone that was not to be.

There was a sense of shared loss and requisite group therapy--as well as passion to move forward--within the CubeSat community that gathered at the 20th annual conference on small satellites, held here at Utah State University earlier this month.

Stolen success

Inan update on the Dnepr failure from ISC Kosmotras, the Russian and Ukrainianrocket-for-hire group, a malfunctioning hydraulic drive unit of a combustion chamberon the booster's first stage has been branded as the root cause of the July 26crash.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Watchingthe launch a few miles away at Baikonur was Dave Klumpar, research professor ofphysics at Montana State University and head of the school's Space Science and Engineering Laboratory. The Dnepr carried the school'sfirst-ever satellite, the Montana EaRth Orbiting Pico Explorer, or MEROPE forshort. It was a proud product of some 5 years of work.

"Wewatched the rocket arc overhead...then there was a bit of a flash anddarkness...followed by a couple of dimmer flashes. That was our first clue thatthere might be something wrong," Klumpar recalled. "At first there was a lot ofuncertainty, followed by total letdown."

"Wewere really looking for a success...to show we built a successful satellite andit operated in the space environment," Klumpar said. "And that was stolen fromus. We can't make that claim."

Educational punch

WhileCubeSats may be petite in size, they pack an educational punch.

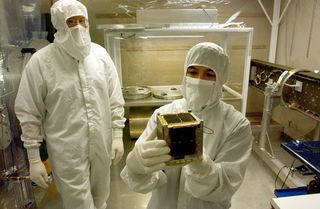

CubeSats measure about fourinches--just 10 centimeters--in size and weigh a mere 2.2 pounds (one kilogram).Their standardized shape makes them cheaper to produce in a much shorter periodof time, with students able to design, build, test, launch and operate thesatellites while still in school.

TheCubeSat Project is an international collaboration of over 80 universities, highschools and private firms busily building the diminutive devices. The tiny,hold-in-the-palm-of-your-hand satellite is built to specifications developed by California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, California and Stanford University's Space SystemsDevelopment Laboratory.

Through companies likeKosmotras, CubeSat launch costs currently translate to about $40,000 per singlecube for the developer.

CubeSatscan perform many tasks. Several duties of the recently destroyed satellites,for example, were to flight qualify a wide variety of small sensors andattitude control devices; take images of Earth; collect data on the electricalstrength of clouds in the ionosphere; as well as chart the Van Allen radiationbelts and test hardware and ideas not yet flown before in space.

Eye-opening experience

"TheDnepr failure was really hard for a while," said Cal Poly's Jordi Puig-Suari,CubeSat Project Co-Director and chair of the university's Aerospace EngineeringDepartment. "I probably didn't realize how hard it hit us. For two weeks wedidn't get too much done. Everybody was in a zombie state," he told SPACE.com.

Puig-Suarisaid that CubeSat teams worked long and hard in readying their respectivesatellites for launch on the Dnepr. "It was a positive step that we made it tothe rocket...not a trivial thing. It was a kind of eye-opening experience and asreal-world as it gets."

AddedWilliam Whalen, a Cal Poly aerospace engineer specializing in thermal vacuumtesting of CubeSats: "It was devastating, obviously, immediately after thefailure." Still, numbers of universities are working on follow-on CubeSats, hesaid.

"We'renot stopping...we're looking for more launch opportunities. We're not going away.This work will continue to continue...and expand," Whalen said. "If you want toplay with the big boys, this is our chance. It isn't just to go up there andshow that we work, but it's also to show that we're resilient."

Mindset is changing

As forthe future of CubeSats, Puig-Suari is taking the small is beautiful route.

"Ithink we're starting to get interesting. The technology is shrinking and we cando useful things," Puig-Suari said, thanks to micro-electronics, powerfulprocessors, tiny cameras and other systems.

"Therewas a lot of skepticism on the part of industry," Puig-Suari said, "thatCubeSats couldn't really do anything useful because of size."

Thatmindset is changing, Puig-Suari added, with CubeSat developers now working onattitude determination, control and pointing accuracy--features that can lead toan array of future applications.

"Thingsare picking up," Puig-Suari suggested. "We're starting to see industry CubeSatsthat are not from universities. NASA is building them; Boeing and The AerospaceCorporation too. That's very different from the past. That kind of shows thatthere's something here that wasn't here before."

Building an infrastructure

Themomentum behind CubeSats won't be shoved off course by an errant booster, said Bob Twiggs, CubeSatProject Co-Director in the Department of Aeronautics & Astronautics at Stanford University, California.

"Wehave always said that getting the student satellites to the launch completes 95percent of the educational goals of the project," Twiggs advised. "There isdisappointment for everyone, but they can also be proud of the achievementsmade in their program. There are many levels of success that we try tostress in the student satellite programs like building an infrastructure at theschools that allow them to do such projects. They learn many skills thatwe can't teach in the class room."

Despite the launch snag, Twiggs said, the CubeSat student efforts aredeveloping the best trained students that will be the next generation of spaceengineers..."and we hope a much larger generation of the general public that hasa renewed interest in space exploration."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He was received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.

Most Popular