The Ursids peak tonight, offering the last meteor shower of 2023 tonight

The Ursids will also light up the sky on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day for skywatchers willing to brave the cold.

The annual December meteor shower, the Ursids, peaks on Saturday (Dec. 23), offering skywatchers willing to brave the cold the opportunity to see meteors in the form of bright streaks of light and the occasional fireball.

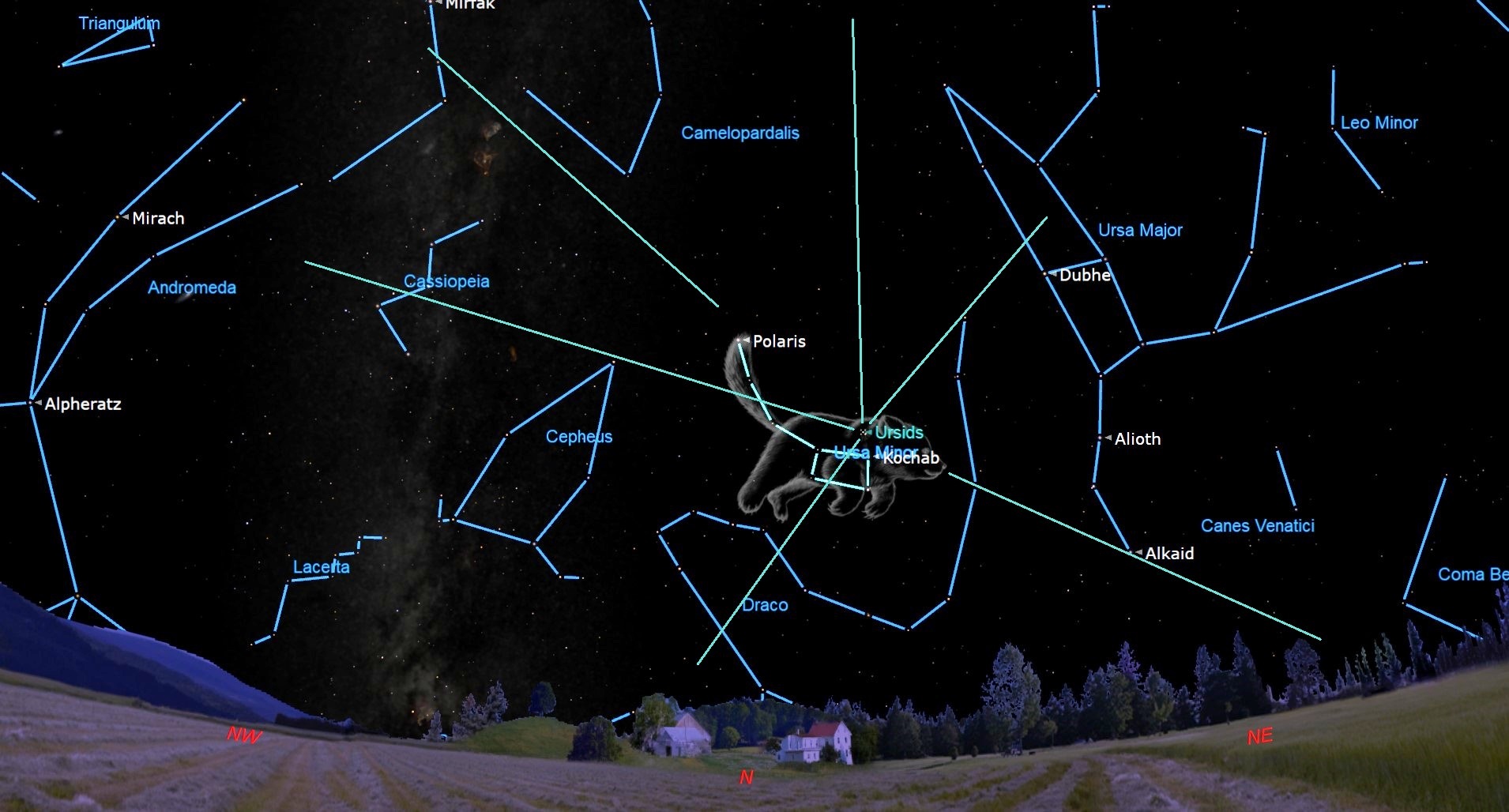

The Ursids is a relatively low-key meteor shower that is active between Dec. 17 and Dec. 26, meaning skywatchers will be able to view meteors from it through Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. The Ursids gets its name from the fact the majority of its meteors appear to stream in from the constellation of Ursa Minor, with astronomers calling this point of high activity the radiant of this meteor shower.

The Ursid meteor shower is most visible when its radiant is above the horizon, and because Ursa Minor is a circumpolar constellation, meaning it is always above the North Pole of Earth. So, for observers in New York City, the radiant is always above the horizon.

The Ursids will peak around 11:00 p.m. EST (0400 GMT), according to In the Sky, and at this time, it could produce around ten meteors per hour. This rate is calculated assuming perfectly dark skies, so in reality, skywatchers can expect to see fewer meteors than this. Unfortunately, the shower has to compete with a relatively bright waxing gibbous moon at 86% illumination, so visible meteors might be few this year.

Related: Night sky, December 2023: What you can see tonight

Looking for a telescope for the next night sky event? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

Like all annual meteor showers, the Ursids are created at around the same time each year when Earth, making its 365.3-day orbit of the sun, passes through a cloud of debris left behind by an asteroid or comet.

These debris fragments enter Earth's atmosphere at high speeds and disintegrate at altitudes of between 45 and 65 miles (70 and 100 kilometers) over the planet’s surface. Occasionally, a larger pebble-sized piece of cometary debris will enter Earth's atmosphere, causing a bright flash or a fireball.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Ursid meteor shower is created from debris left around the sun by comet 8P/Tuttle. 8P/Tuttle, or just "Tuttle," is classed as a midsized comet, but it still has a diameter of around 2.8 miles (4.5 kilometers), making it around the size of the island of Manhattan and larger than around 99% of known asteroids.

As Tuttle gets close to the sun on its 13.6 Earth-year-long orbit, radiation from our star heats material within it, causing it to turn from solid ice to gas, a process called sublimation. As this gas escapes the comet, it blasts away solid material from Tuttle's surface. This material settles around the sun into lanes of dust grains and larger fragments.

Tuttle’s last close approach to Earth and passage through the inner solar system was in January 2008, when it came to within around 23 million miles (37 million km) of our planet. The comet won’t come as close to our planet again until Dec. 28, 2048, when it will pass us at around 26 million miles (42 million km) of Earth.

The year 2130 will be a special one for Tuttle and the Ursids because around the time the shower peaks that year, their parent comet will pass by Earth on Christmas day at a relatively close distance of around 14 million miles (23 million km), over ten times closer to the Earth than our planet is to the sun.

If you are hoping to catch a look at the Ursids or any other night sky sight, our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start.

And if you're looking to snap photos of the Ursids or the night sky in general, check out our guide on how to photograph meteor showers, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap the Ursid meteor shower and would like to share it with Space.com’s readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.