Total Solar Eclipse Offered Rare Opportunity to Predict Sun's Corona

The sun is entering a low-point in activity.

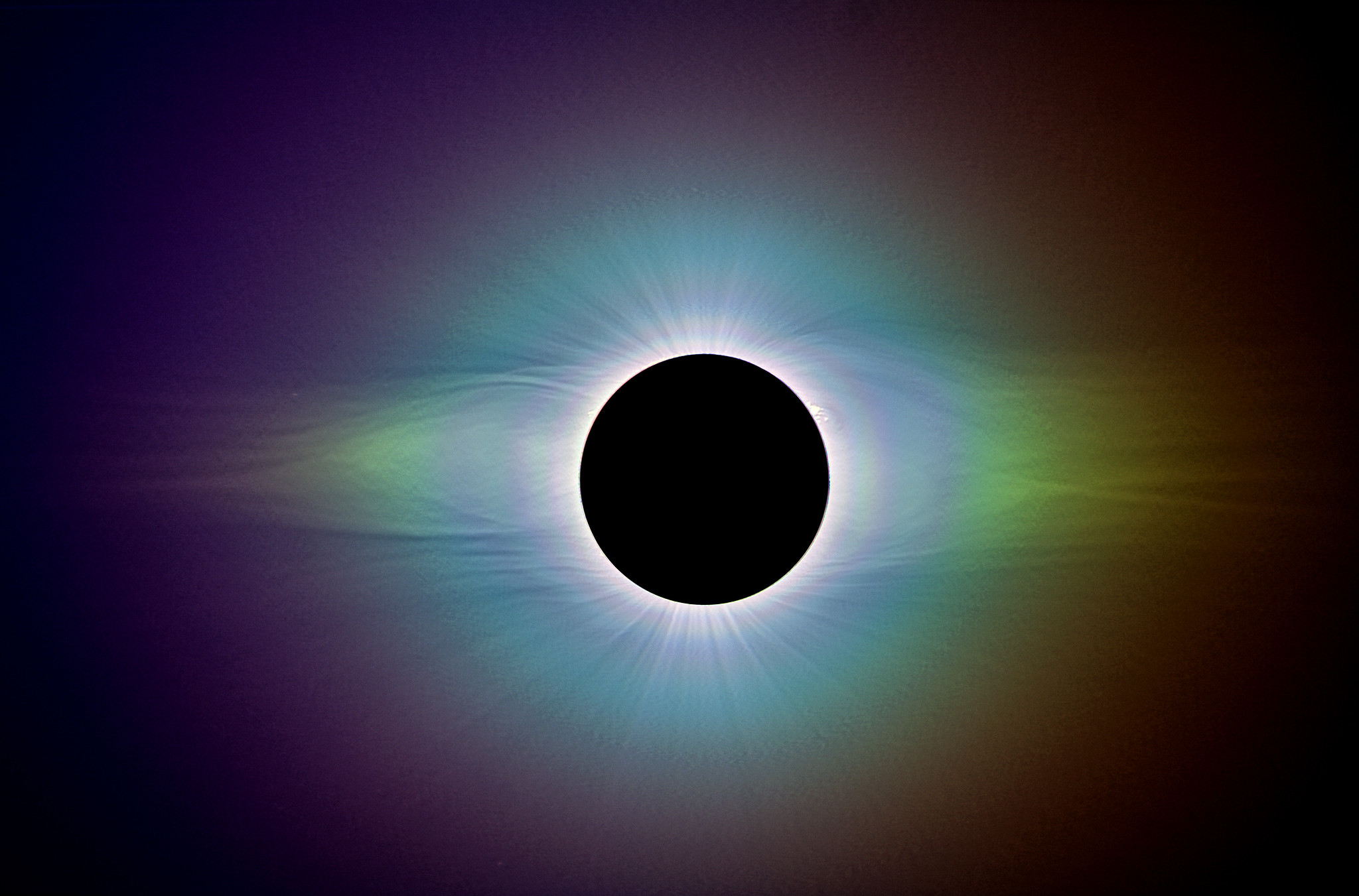

The corona of the sun looks like a wispy, glowing ring to skywatchers viewing the totality of a solar eclipse. But this enchanting halo is also a scorching blaze of plasma with the potential to disrupt satellite, radio and GPS systems around Earth.

Therefore, developing accurate predictions of the corona's changing structure is important. And when the July 2 total solar eclipse crossed South America, a small group of scientists waited to see if the models they made using NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) data matched up with pictures taken of the real thing. The space agency detailed this work in a statement published on Wednesday (July 3).

The corona is the sun's blazing outer atmosphere. The magnetic field of the sun changes the structure of the corona, which releases gusts of charged particles into the solar system. Known as the solar wind, this flow creates the space weather that prompts auroras near Earth's poles, but which can also interfere with the extensive communications systems underlying modern society.

Related: Twofer! Total Solar Eclipse, Hurricane Barbara Spotted From Space (Photo)

Usually, the corona is invisible, blotted out by the brightness of the inner layers of the sun. That's why eclipses are valuable opportunities to study the corona from Earth.

A team from the private, computational-physics research company Predictive Science Inc. used data from SDO, which launched in 2010, to refine a numerical model they'd previously used to predict the appearance of another total solar eclipse: the iconic event that crossed the continental United States in August 2017.

For this week's eclipse, the team focused on the solar poles in particular. That's because the sun is currently going through a lull in its 11-year cycle. During this low-activity period, called solar minimum, the poles strongly affect the star's magnetic activity — and therefore the corona's structure.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By running the model on Pleiades, "one of the world's most powerful supercomputers" according to the agency, the researchers came up with a detailed prediction featuring a cloudy corona with two wide, hazy streamers on opposite sides of each other. They published their final total-eclipse prediction on June 25.

Now, they've compared that prediction with how the corona really looked on July 2. While their hypothesis was not totally accurate, the researchers were happy to see how close they got.

"I'm thrilled," Predictive Science researcher Cooper Downs said in the statement. "I'm already looking at the details we got wrong and where we can improve. But it's fantastic to see there will be quality scientific measurements that we can compare in detail to, and much to learn from, that comparison."

SDO and missions like NASA's Parker Solar Probe and the European Space Agency's upcoming Solar Orbiter will be gathering more data about the corona in the years to come.

- How to Catch the Next Eclipse: A List of Solar and Lunar Eclipses in 2020 and Beyond

- Solar Eclipse Photography: Tips, Settings, Equipment and Photo Guide

- Solar Wind Leaves 'Sunburn' Scars on the Moon

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.