'Ring of fire' solar eclipse 2020: Here's how it works (and what to expect)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Update for June 21: The 2020 annular solar eclipse wowed skywatchers across Asia and Africa. See the amazing photos in our story here.

The first full day of summer in the Northern Hemisphere will bring with it one of nature's great sky shows: an annular solar eclipse.

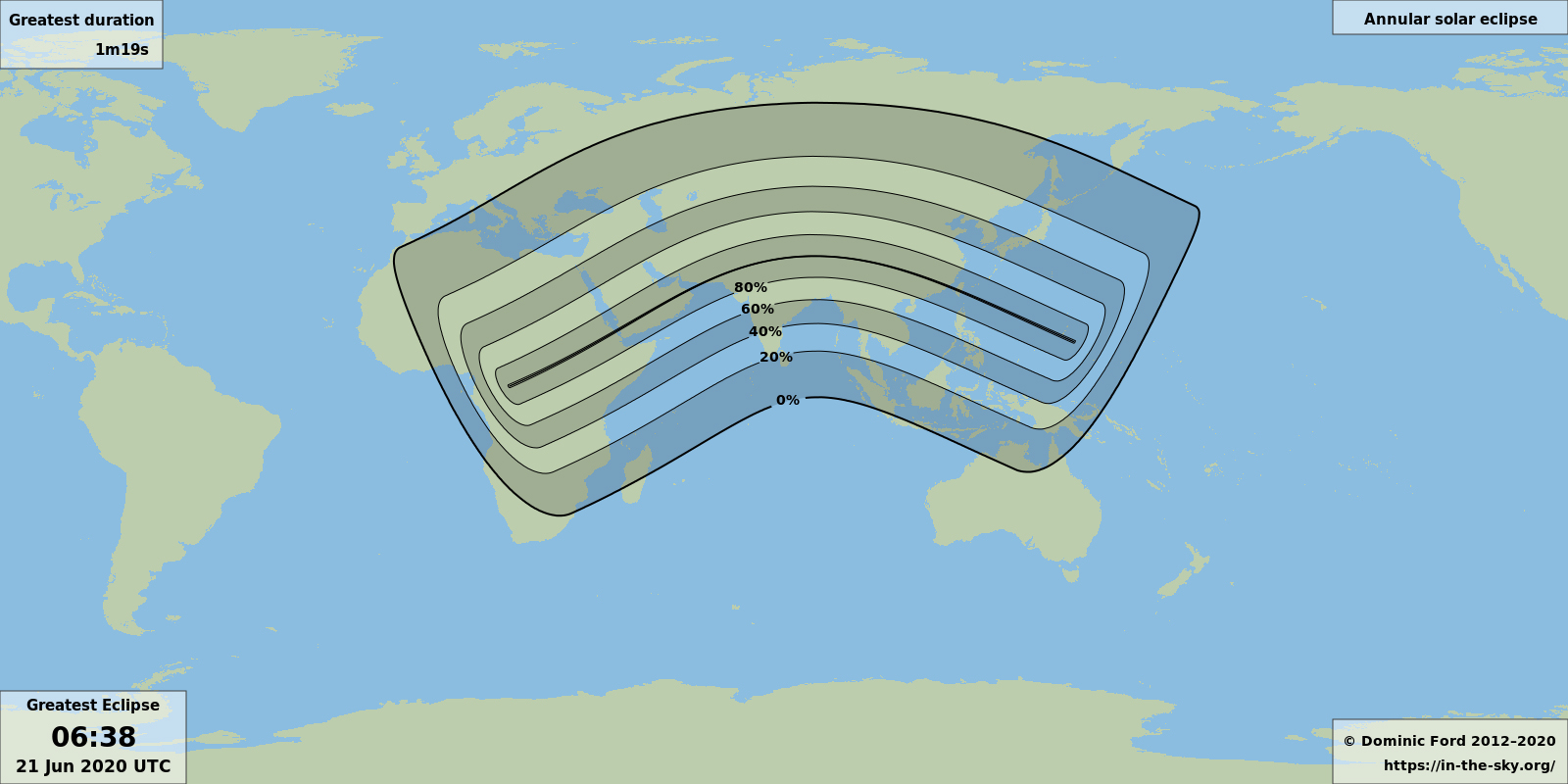

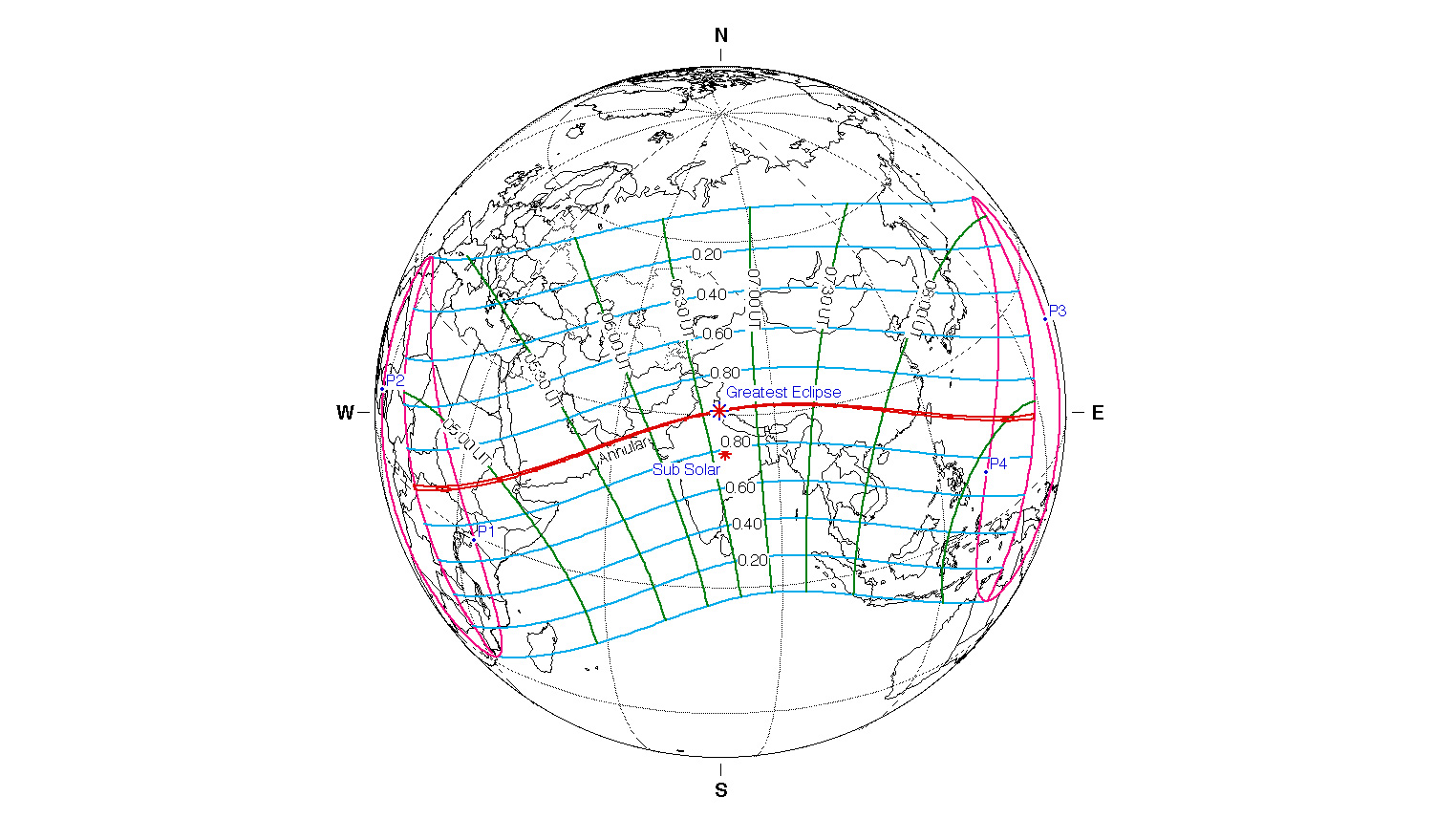

On Sunday (June 21), the new moon will orbit between the sun and Earth and will pass squarely across the face of the sun for viewers along a very narrow path that will run through central and northeast Africa, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, northern India, southern China and Taiwan. But instead of completely blocking the sun, it will leave a "ring of fire" from the sun when it peaks.

You can watch the event live online in these webcasts if you don't leave near its visibility path. Most webcasts begin at 1 a.m. EDT (0500 GMT). The eclipse itself begins at 11:45 p.m. EDT Saturday, June 20 (0345 GMT Sunday), peaks at 2:40 a.m. EDT (0640 GMT) and ends at 5:34 a.m. EDT (1034 GMT) June 20. Here's a list of times for the start and end of the eclipse, depending on your viewing location, from Dominic Ford of In-The-Sky.org.

IMPORTANT: Be sure to wear proper eye protection like eclipse glasses if you observe the eclipse in person!

Related: Solar eclipse guide 2020: When, where & how to see them

More: How Solar Eclipses Work (Infographic)

Not quite a total eclipse

If you see the 2020 annular solar eclipse, let us know! Send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com to share your views.

During a total eclipse of the sun, the entire disk of the sun is covered by the moon. The end result is a beautiful spectacle in which a beautiful halo of pearly white light — the solar corona — suddenly flashes into view. Semidarkness settles over the landscape and a few of the brighter stars and planets may appear. Then after a few seconds or minutes, totality ends and the great show is over.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But an annular eclipse, such as the one that will take place on Sunday, falls just short of providing such a celestial pageant, because the moon will be just a little too far from the Earth to completely cover the disk of the sun. The dark conical shadow of the moon (called the umbra), from where we can see a total eclipse, extends for 235,600 miles (379,100 kilometers) out into space.

But unfortunately, on Sunday, the moon's distance from Earth will be 237,100 miles (381,500 km) from Earth. So the moon's dark umbral shadow will fall 1,500 miles (2,400 km) short of reaching the Earth’s surface. In such a case, an annular eclipse results.

We can imagine a "negative shadow" or anti-umbra, as the mirror image of the umbra, beginning at the tip of the umbral shadow and extending out to infinity. The ground track of the anti-umbra traces out a "path of annularity" and observers who are within this narrow shadow track, which will average about 33 miles (53 km) in width, will see the dark silhouette of the moon, surrounded by a ring of bright sunlight.

That ring will be exceedingly narrow; the moon's apparent diameter will be 99.4% as large as that of the sun, so the width of that ring of sunlight at its thinnest will measure no more than six-tenths of one percent of the sun.

Thus a bright ring of the sun's disk will remain uneclipsed, unfortunately bright enough to prevent a view of the solar corona and keeping the sky just bright enough to squelch any view of the stars and most of the planets. The term annular is derived from the Latin word annulus, meaning "ring shaped," and in recent years, the mainstream media have branded such events as "ring of fire" eclipses.

In Photos: Annular Solar Eclipse of May 20, 2012

'Ring of fire' solar eclipse explained

While admittedly an annular solar eclipse cannot compare to a total one, it is still a most interesting and exciting celestial event. Here is a guide to give you an idea of what you can expect to see.

First, be sure to be watching at the time the eclipse is live (most of the webcasts listed here begin at 1 a.m. EDT or 1:30 a.m. EDT (0500-0530 GMT). The most interesting period will likely be centered on the time of greatest eclipse, which will come at 2:40 a.m. EDT (0640 GMT) on Sunday (or if you live in the Pacific Time Zone, Saturday night at 11:40 p.m. PDT).

Along the path of the annular eclipse, the partial phase will last about 90 minutes before and after the ring phase of the eclipse.

First contact of the moon with the sun is essentially undetectable, but within a few minutes observers will see the moon cutting a scallop out of the lower right-hand edge of the sun. For approximately the next one and a half hours the moon will slowly move across the face of the sun.

If the foliage around the observer is suitable, tiny overlapping crescents of light may be shown, dappling the ground beneath trees, the result of innumerable "pinhole camera" effects as sunlight filters through the leaves.

Related: Solar Eclipse Photography: Tips, Settings, Equipment and Photo Guide

Cut down to a crescent

By the time the sun is 80% eclipsed, it will have the shape of an elongated crescent. Sunlight will be coming only from the sun's redder limb regions; overall illumination on the ground will be dusky and yellow, becoming progressively redder until the moment of annularity.

On-site observers will probably allude to how much cooler the air is getting; temperatures may drop 10 degrees Fahrenheit (6 degrees Celsius) or more. Cumulus clouds — those clouds that resemble big balls of fluffy cotton — will tend to dissipate, but ground fog might form in lowlands. Shadows will become distinctly sharper as the sun becomes more and more misshapen, narrowing to a thin arc or filament of light.

Because the geometry of this event is almost like that of a total eclipse, there is every reason to check a few minutes before and after annular eclipse, for faint, mysterious rippling waves of dark and light moving across the ground or along the sides of buildings. Called "shadow bands," these waves apparently result from irregularities in the Earth's atmosphere.

As the ring phase approaches, events will accelerate: a weird “counterfeit twilight” will fall across the landscape. The eerie dimming at midday, while admittedly not so dramatic as during a total eclipse, may bring about unusual behavior by birds, livestock, and insects.

No stars are likely to be seen, but it should be easy to spot Venus, shining at a brilliant magnitude of -4.5, 25 degrees west of the sun. (Your closed fist covers about 10 degrees of the sky when held out at arm's length.)

Beads of light

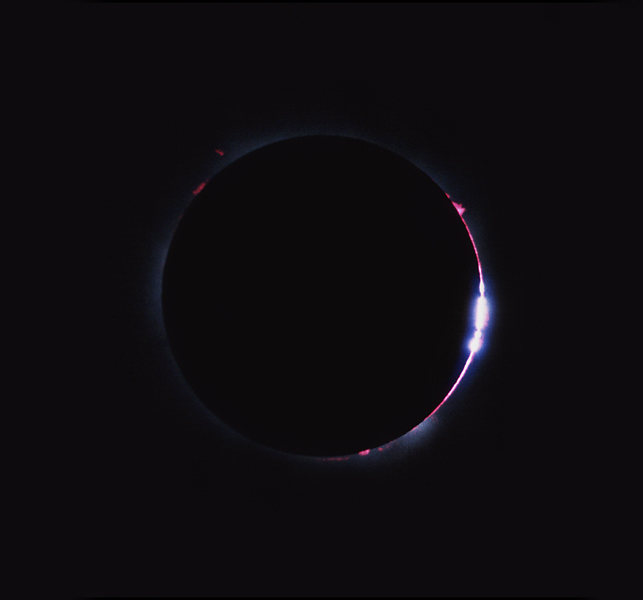

Probably the most readily observable phenomenon at Sunday's eclipse will undoubtedly be the formation of Baily’s beads.

These are the lingering glints of sunlight appearing through valleys on the eastern limb of the advancing moon, just as a total eclipse begins, and then at the western limb when it ends. The nearly identical sizes of the disks should also cause beads to appear at the northern and southern limbs of the moon as well, depending on an observer’s location within the central path.

It is not well known that Francis Baily's original sighting of the beads occurred at the eclipse of May 15, 1836, which was annular rather than total. By the time the narrowing crescent had grown so that it nearly encircled the sun, with a 40-degree gap remaining between the cusps, Baily saw a row of lucid points spring up between them suddenly, as if ignited by a fine train of gunpowder.

In the next few seconds the points elongated and gradually fused together, but what especially fascinated him, as recounted in Robert Gran's 1852 History of Physical Astronomy, was the manner in which the last few lunar mountains seemed to stretch out, almost as if the moon’s edge were "formed of some dark, glutinous substance, which by its tenacity adhered to certain points of the sun's limb, and by the motion of the moon was thus drawn out into long threads ..." When these dark threads finally snapped, the moon's limb recovered its fairly smooth appearance and was already perceptibly advanced on the face of the sun.

In any case, since the upcoming eclipse is also annular, observers might want to be on the lookout both at the beginning and end of the annular phase for the dark threads Baily described.

Near the beginning and end of the annular track, the "ring of fire" may last as long as 82 seconds. At the middle of the track in northern India, the duration of annularity will last only 38.2 seconds.

After the annular eclipse has ended, everything will happen in reverse order as the moon continues on its way, gradually uncovering more and more of the sun.

Next year, it’s our turn!

While this eclipse will be exclusively an Eastern Hemisphere event, North America will not have very long to wait to see an annular eclipse of its own. In less than a year — June 10, 2021 — the path of an annular solar eclipse will track from the northern shoreline of Lake Superior, north-northwest across James and Hudson Bay, through Nunavut and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago on up to the North Pole.

Meanwhile, New York State, New England and Eastern Canada, will be treated to the sight of a large partial eclipse which will coincide with sunrise. Instead of coming up as it normally does, resembling an orange-yellow disk, on this June morning the sun will emerge above the east-northeast horizon resembling a scimitar or a horseshoe with upturned pointed tips.

Editor's Note: If you capture a stunning photo of the solar eclipse and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photos, comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

- The 8 most famous solar eclipses in history

- Solar eclipses: An observer's guide (infographic)

- Eclipse season 2020 has arrived! Catch 2 lunar eclipses and a 'ring of fire' this summer

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.