How to Use Mobile Astronomy Apps to View the Mercury Transit of 2019

On Nov. 11, 2019, the world will witness a rare transit of Mercury across the disk of the sun. You'll need a telescope equipped with a proper solar filter to view the five-hour event — but whether you can see it at all depends on where you live.

In this edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll highlight the 2019 transit of Mercury and tell you how to use your favorite astronomy app to preview it and follow the progress of speedy Mercury across the disk of the sun. We'll also show you how to virtually view past and future transits, and even fly to Mars and Jupiter and watch Earth transit the sun!

- Mercury Transit 2019: Where and How to See It on Nov. 11

- Teach Your Kids About the Mercury Transit of 2019: A NASA Guide

- How to Watch the Mercury Transit Live Online

Inner planets can cross the sun

Mercury orbits the sun every 88 days. From our vantage point here on Earth, the speedy planet passes the sun twice in every orbit — once when it's between us and the sun, and once when it's on the far side of the sun. These events are called solar conjunctions, and all planets experience them. But only Venus and Mercury can produce solar inferior conjunctions — when they pass between us and the sun.

Mercury's orbit is tilted by 7 degrees with respect to Earth's orbit — which we draw on the sky as the ecliptic. The two points in space where Mercury's orbit crosses the ecliptic are called nodes. Most of the time, when Mercury passes the sun at inferior conjunction, it misses the sun by several degrees. But if the sun is near either of the two nodes, Mercury can cross, or transit the disk of the sun — as seen from our vantage point on earth.

Solar eclipses by the moon work by the same principle; as a matter of fact, a Mercury transit is actually a partial solar eclipse, since it hides a tiny bit of the sun. But while the moon's disk is large enough to cover the sun quite frequently, the tiny disks of Mercury (and Venus) require a much more precise alignment — and so the transits are rare.

Transits of Mercury always occur in early May or mid-November, and are more common than transits by Venus. There are typically about 13 or 14 Mercury transits per century. The last transit was on May 9, 2019. The next one after Monday will occur on Nov. 13, 2032 — so it's worth trying to see this one!

Transits of planets have stages. First contact is defined as the moment that the edge of the planet first touches the edge of the sun. Second contact occurs when the planet is first completely within the sun's disk — usually about 90 seconds after first contact. This is a terrific time to watch the transit through a safely filtered telescope.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If the geometry of the encounter has Mercury crossing near the center of the sun, the transit time will be five or six hours. It will be extremely short if the planet crosses close to the northern or southern pole of the sun — and of intermediate duration between those two extreme cases.

The final stages of the transit are third contact, when the planet is about to move off the opposite side of the sun's disk, and fourth, or last, contact — the last moment when the planet's edge is touching the sun's edge. This stage, too, is very brief and exciting to view close-up.

Let's review the details of Monday's transit and show you how to preview it on your favorite astronomy app — or to follow along if you don't own a solar-filtered telescope, or live where it's visible.

The transit of Mercury in 2019

Monday's transit of Mercury will be visible from all of North America, but only the eastern portion of the continent will see the first and second contacts with the sun. The Eastern seaboard, the Caribbean, Central and South America, and the western edge of equatorial Africa will see the entire event from start to finish.

For the rest of North America and the Pacific Ocean region, Mercury will already be crossing the sun at sunrise. For Europe, the Middle East, and the rest of Africa, the sun will set before Mercury has completed its journey. Asia and Oceania will not see any of the Eclipse. Eclipsewise.com, which is an excellent resource for solar and lunar events, has a good map that shows the zones of visibility.

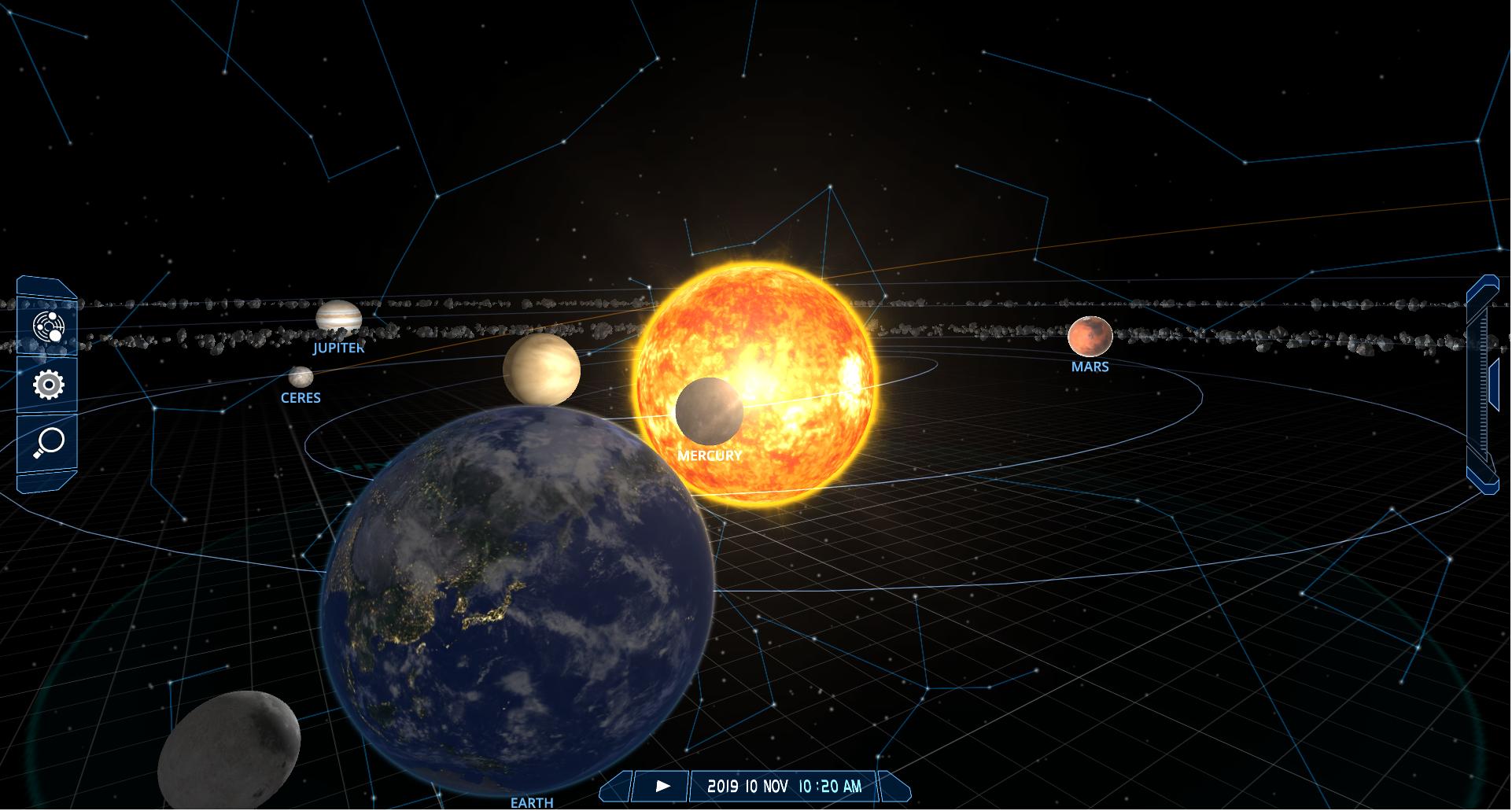

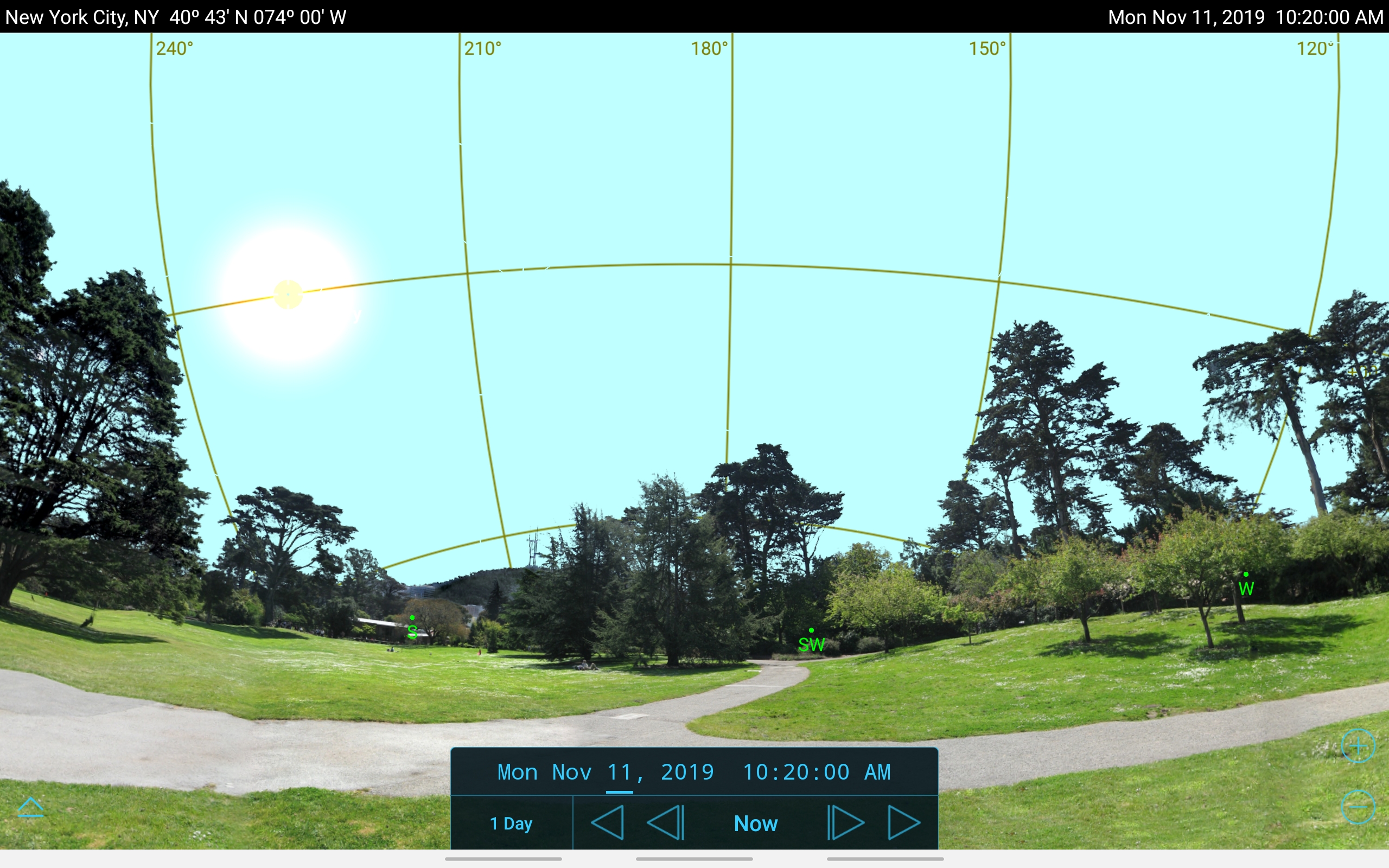

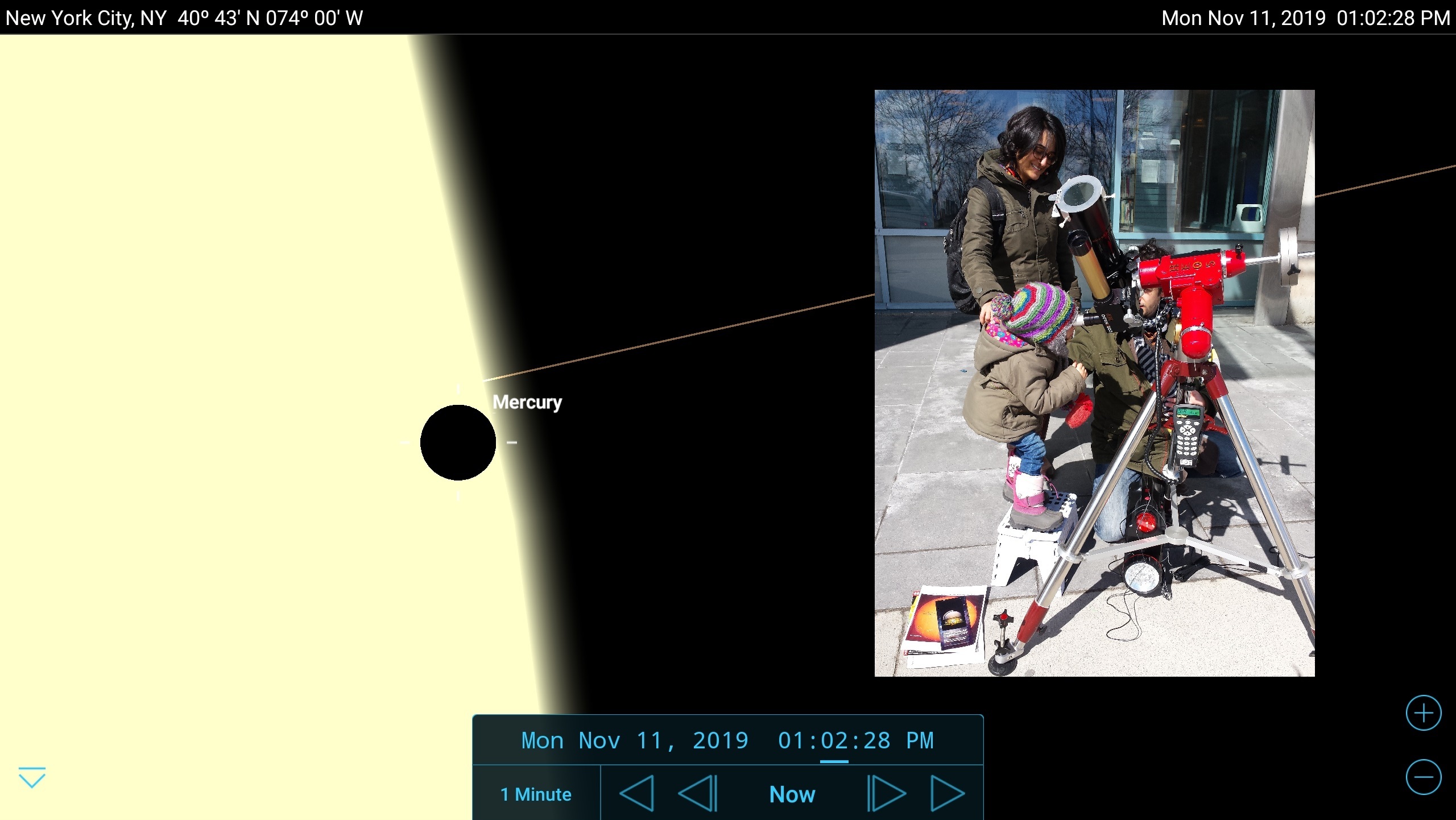

First contact will occur at 12:35:27 GMT, and last contact will occur at 18:04:14 GMT. To find out whether the transit will be visible where you live and to preview what it will look like, use an astronomy app such as SkySafari 6, Star Walk 2, or Stellarium Mobile. Open the app and then search for and center Mercury — don't worry if it's below the horizon at first. Next, set the app's date to Nov. 11, 2019 and the app's time to mid-transit — about 15:20 GMT. That time converts to 10:20 a.m EST and 7:20 a.m. PST. To convert to your local time zone, add or subtract the correct number of hours from GMT, or use a converter like this one from Timeanddate.com

For locations in North America, the app will show the sun low in the southeastern sky at mid-transit. By running time forward, or by stepping hour by hour, you can watch the sun move across the sky at your location. If the sun doesn't rise at all during the time range I've given above, the transit isn't visible for you. If it rises or sets during the time window, at least you can obverse the first or second pairs of contacts.

Next, return your app to mid-transit and zoom in on the display until the sun shows as a good sized disk, and look for Mercury as a tiny black dot on its face. You can run the time forwards and backwards to follow Mercury's progress over time.

Mercury's tiny disk will not be visible through eclipse glasses or most filtered binoculars. You'll need a properly filtered telescope. Any size will do — but be sure to affix proper solar filters BEFORE aiming your telescope anywhere near the sun!

If you plan to view the transit, or photograph it through a filtered telescope, use your app to note the direction and how high above the horizon the sun will be during the various stages of the event. That way you can scout out a viewing spot where the sun will be visible throughout the transit duration.

The next transit of Mercury will occur on Nov. 13, 2032. You can easily preview that event using the same steps.

Going beyond

Transits of the inner planets were used historically to advance our knowledge of them, and of our solar system. NASA has a web page of educational activities that compliment the transit of Mercury.

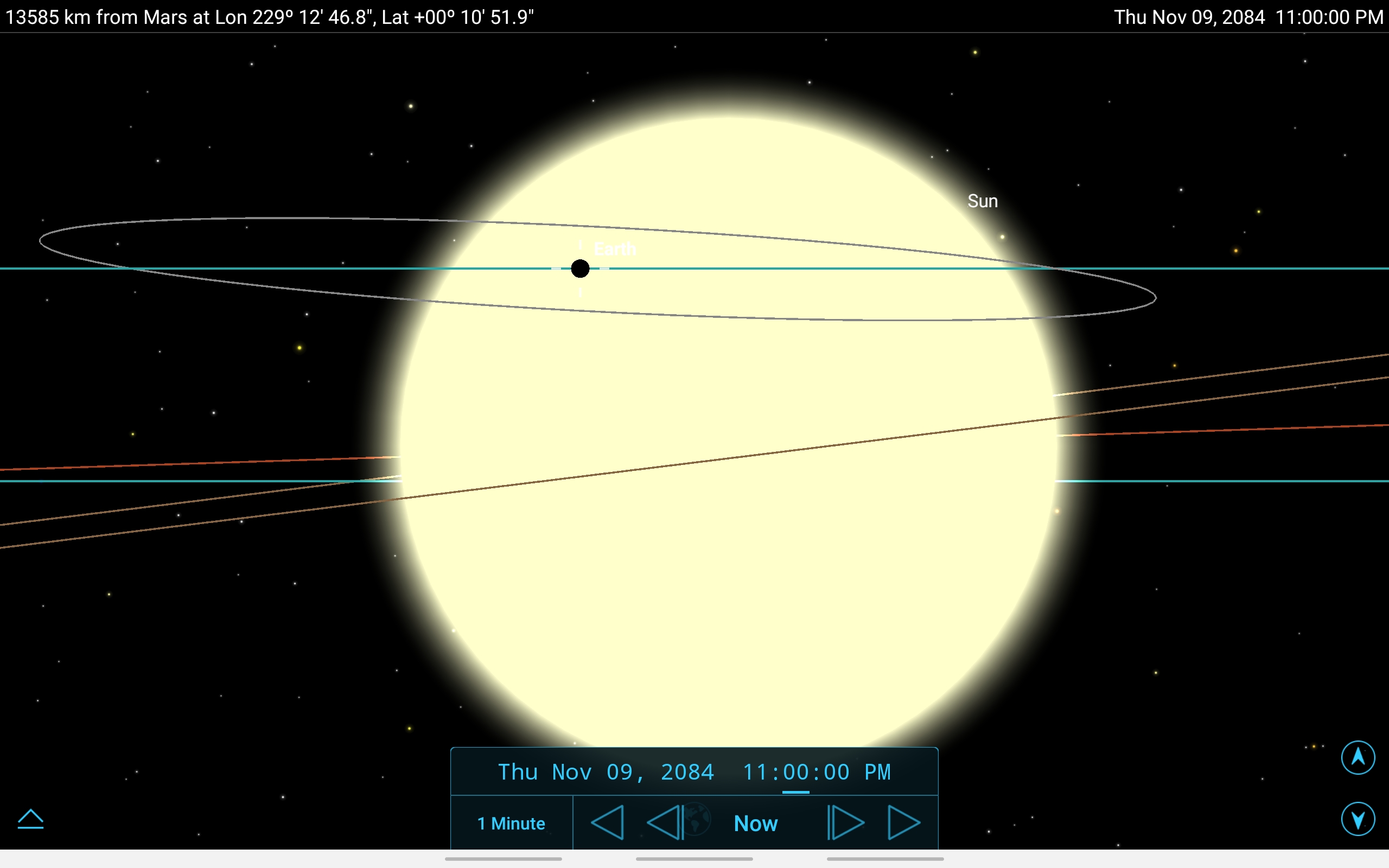

With SkySafari, you can see Earth transit the sun from Mars or another planet. From Mars, Earth transits the sun in pairs of transits that are separated by 79 years. The last one was on May 11, 1984. The next one will be on Nov 9, 2084. In SkySafari 6, search for Mars and select it the Orbit option. Once there, perform a search for Earth and tap the Center option. Set the app's date to either of the dates above. (You can enter years manually in the Settings/Date & Time menu.) Zoom in on the Earth and sun and adjust the hour to see the Earth transit the sun! Maybe someone you know will be living on Mars in 2084, and will see the event first-hand! (To return the app to normal sky view, just tap Now and then close the Time Control panel, and then tap the Earth icon.

Viewed from Jupiter, Earth will make a grazing transit of the sun on Jan 10, 2026. Try it!

In future editions of Mobile Astronomy, we'll preview the astronomical highlights in 2020, view constellations in three dimensions, and more. Until then, keep looking up!

Editor's note: Chris Vaughan is an astronomy public outreach and education specialist at AstroGeo, a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, and an operator of the historic 74" (1.88-meter) David Dunlap Observatory telescope. You can reach him via email, and follow him on Twitter @astrogeoguy, as well as on Facebook and Tumblr.

- Mercury Transit 2019: How to Watch the Rare Event Live Online

- Put a Personal Astronomer in Your Pocket Using Mobile Apps

- The Mercury Transit of 2016 in Amazing Photos

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.