Mercury Transit 2019: Photos, Videos and Explainers for the Rare Sight

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The 2019 Mercury transit has ended; read our full story about the event here.

Today, people across most of the world had the chance to catch the planet Mercury passing across the sun. This rare event won't be seen from Earth again until 2032, so we put together this guide on the science behind the sight and how best to observe it yourself.

The smallest planet in the solar system is also the closest to our star, and occasionally it crosses in front of the sun's bright disk from our perspective here on Earth. The last time this happened was in 2016, but after this upcoming transit, we'll have to wait another 13 years to see the next one.

What You Need | Webcasts | Timeline | 1st Photos!| Find an Event

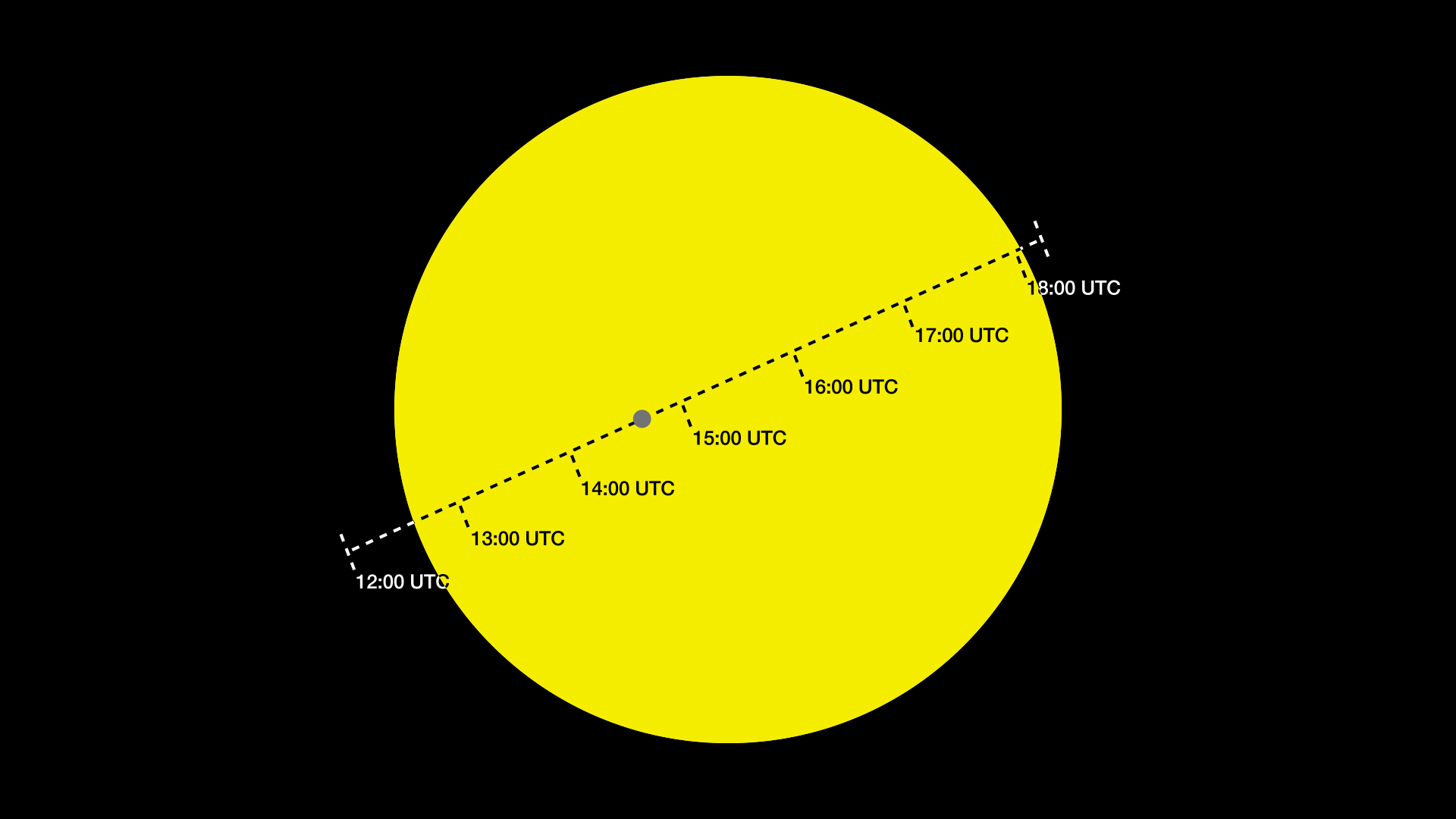

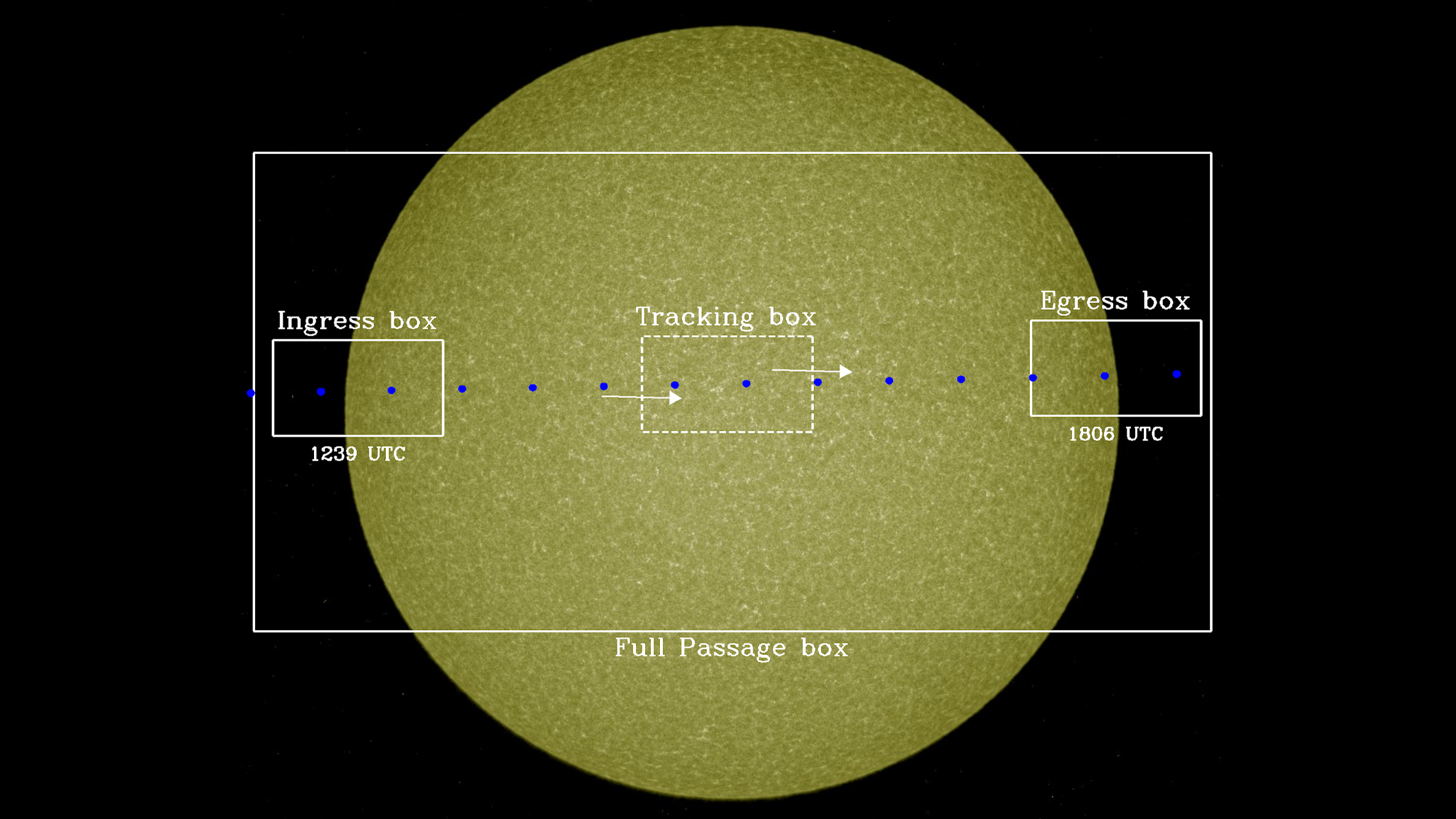

Mercury began its journey across the sun at 7:35 a.m. EST (1235 GMT), and the entire transit took roughly 5 and a half hours, ending at 1:04 p.m. EST (1804 GMT), according to NASA.

The planet currently looks like a tiny, traveling blemish on the sun's face as it passes in front of the sun. The transiting world will be so small that skywatchers will need special gear — telescopes or binoculars equipped with protective solar filters — to see it.

Related: The Mercury Transit of 2016 in Amazing Photos

Read our full coverage:

How to Observe the Mercury Transit

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- How to Film the Mercury Transit of 2019

- How to Watch the Mercury Transit Live Online

- How to Find a Viewing Event Near You

- Here's the US Weather Forecast for the Monday's Rare Mercury Transit of 2019

- Mercury Transit 2019: Here Are the Stages to Watch

- The Gear You Need to Safely Watch the Mercury Transit

- How to Use Mobile Astronomy Apps to View the Mercury Transit of 2019

- How to Safely Observe the Sun (Infographic)

- Make a Safe Sun Projector with Binoculars (Video)

Mercury Transit Science

- The Mercury Transit of 2019 Has Begun

- Here's Why Mercury Transits Are So Rare

- Teach Your Kids About the Mercury Transit of 2019 with This NASA Guide

- How a Spacecraft Fleet Will Watch the Rare Mercury Transit from Space

- The Science of the 2019 Mercury Transit: How Astronomers Will Study It

- A Mercury Transit for the Ages: November 1973

- Mercury Transit 2019: The Astronomical History of This Rare Celestial Event

Editor's Note: Visit Space.com on Nov. 11 to see live webcast views of the rare Mercury transit as shown from telescopes on Earth and in space, along with complete coverage of the celestial event. If you SAFELY capture a photo of the transit of Mercury and would like to share it with Space.com and our news partners for a story or gallery, you can send images and comments in to spacephotos@space.com.

Mercury's transit explained

Need more space?

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our Solar System and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Save up to 61% on 13 issues for the year!

Mercury and Venus are the only planets that can pass in front of, or transit, the sun as seen from Earth, because their orbits are between the sun and Earth's orbit. Mercury's average distance from the sun is 35,983,095 miles (57,909,175 kilometers), or about 30% of the average distance between the Earth and the sun.

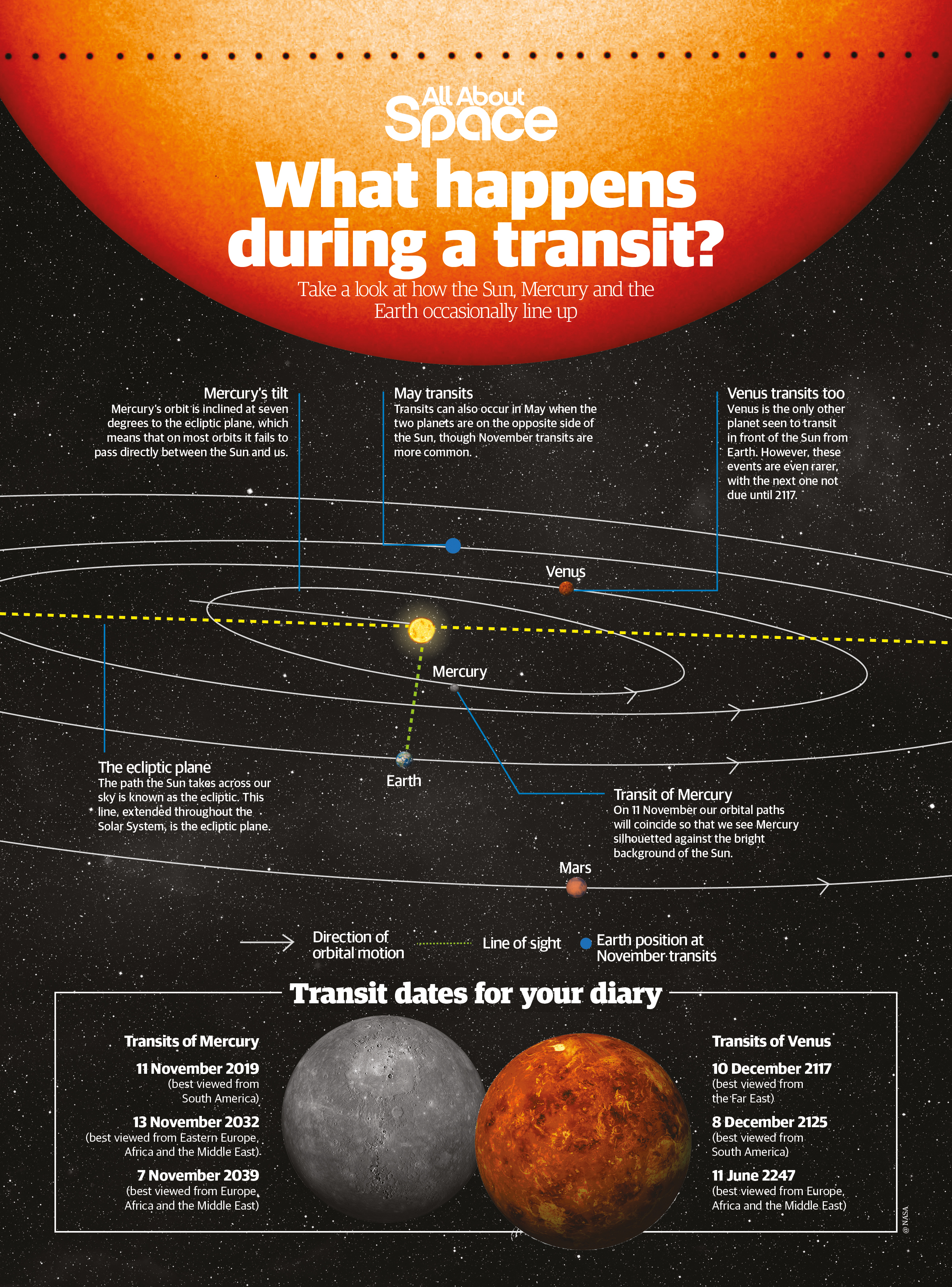

Transits are rare events. From Earth, Mercury can be seen moving across the sun's face about 13 times every hundred years, on average. For a transit to occur, Mercury's got to be in the right place at the right time.

Let's use breakfast to illustrate. Picture the solar system as a cosmic fried egg. The sun is the yolk, and the planets orbit it within the flat plane of the egg white. Mercury and Earth move in orbits slightly tilted to one another, so if these orbits were drawn out in 3D within the egg white, and if you were to look toward the middle of this egg from the side, there would be two points at which Mercury's orbit and Earth's orbit would appear to overlap.

Currently, these points occur in early May and early November; that's the window of time when Mercury transits could be visible from Earth. People on Earth don't see a Mercury transit every year, however, because each planet takes different lengths of time to orbit the sun, so Mercury and Earth don't always coincide at those two places where the orbits overlap, called nodes, at the same time.

There are four key parts to the entire event, beginning with the first contact, or the moment Mercury's silhouette first touches the edge of the sun, Dean Pesnell, project scientist from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), said in an Oct. 23 blog post. Another way to describe it is to say, "when the planet's disk is externally tangent to the sun," according to astrophysicist Fred Espenak, aka "Mr. Eclipse," who runs the skywatching website eclipsewise.com.

Second contact occurs at the instant that Mercury appears to have moved completely in front of the sun, Pesnell wrote. Third contact is when Mercury begins to cross over the edge of the sun's disk near the end of the transit, and fourth contact is the last moment Mercury's shadow touches the edge of the solar disk, marking the end of the transit.

Where to see it

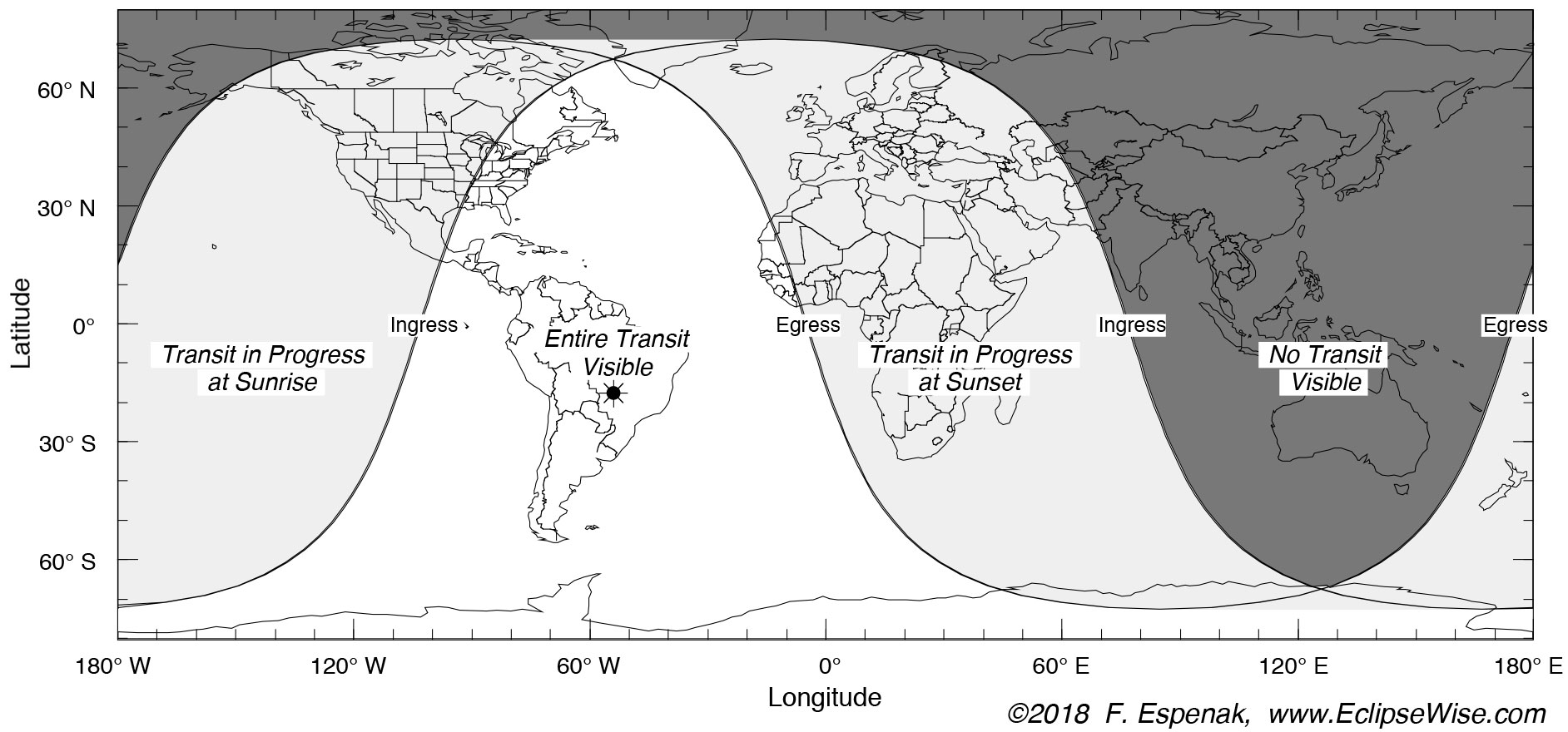

Mercury's transit will be visible from most of North America; all of South America; all of Africa; and parts of Europe, Asia and Antarctica. According to a map developed by Time and Date, skygazers in cities like New York, Montreal and Sao Paulo will be able to see the entire transit, and people in Honolulu, Rome and Cairo can catch part of Mercury's trip.

| Header Cell - Column 0 | UTC | EST | CST | MST | PST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact I | 12:35 | 7:35 a.m. | Not visible | Not visible | Not visible |

| Contact II | 12:37 | 7:37 a.m. | Not visible | Not visible | Not visible |

| Greatest | 15:19 | 10:19 a.m. | 9:19 a.m. | 8:19 a.m. | 7:19 a.m. |

| Contact III | 18:02 | 1:02 p.m. | 12:02 p.m. | 11:02 a.m. | 10:02 a.m. |

| Contact IV | 18:04 | 1:04 p.m. | 12:04 p.m. | 11:04 a.m. | 10:04 a.m. |

Viewers on the U.S. East Coast can watch the entire transit, because the sun will already have risen by the time the event begins. Certain Midwesterners, like those viewing from Columbus, Ohio, can also catch the tiny silhouette of Mercury entering and leaving the sun's disk. But skywatchers west of the Mississippi River will miss part of the event, because the transit will already be underway by the time the sun rises there. There will be plenty of time to enjoy it, however, because the event will last for 5 hours, 28 minutes, 47 seconds, according to Time and Date. For example, folks in San Francisco, California, will have over 3 hours of viewing time after sunrise.

Visit this interactive map on Time and Date for local transit and sunrise (or sunset) times.

What to expect

Viewers who pay close attention to Mercury's transit can catch some interesting visuals.

Time-lapse photos or videos, for example, will reveal that Mercury moves in a curved line over the sun, and the planet's path will vary according to your location on Earth. From New York, it will appear to begin at the bottom left section of the sun, curving upwards towards the right and then tapering off. But from Santiago, Chile, Mercury will first appear on the bottom right, then approach the center of the solar disk before curving downwards.

Then there's also the "blackdrop effect," in which the tiny shadow looks like a teardrop connected to the blackness of space when it's near the edge of the solar disk. Astronomers believe this effect is due to diffraction, as light waves bend around the sides of Mercury.

How to see it (safely)

Even if you don't have access to safe sun-gazing equipment, you still have many ways to view the event. One of the most exciting will come directly to your internet browser, put together by NASA's solar scientists, engineers and web programmers.

Beginning at about 7 a.m. EST (1200 GMT) on Nov. 11, just as Mercury moves over the sun's corona, or its outermost layer, SDO will begin recording videos and images of the transit and adding self-updating movies to NASA's Mercury Transit website.

The observatory will get about a 30-minute head start on observing the event, because it has the unique ability to observe the sun's corona from space — something that cannot be observed from Earth (except when the moon is blocking out the sun in a total solar eclipse). While SDO can see Mercury passing through the corona, skywatchers on Earth will have to wait until Mercury begins to cross in front of the sun's photosphere, or the part that's visible from Earth.

"Ingress box" imagery uploaded to that site will show viewers Mercury as it begins its sweep through the corona and onto the photosphere; "Tracking box" imagery will follow the planet's trip across the solar disk; "Egress box" imagery will follow the planet's exit, and "Full Passage box" imagery will showcase the entire transit in all its glory.

Safety first!

Special solar filters need to be on all telescopes or binoculars pointed at the sun. Sunglasses or tinted shades will not protect your eyes from permanent damage. Do not look directly at the sun without a solar filter!

Please note that solar eclipse glasses paired with binoculars or telescopes do NOT do the trick; that combination is even more dangerous than staring at the sun with your naked eyes — which can cause permanent blindness — because lenses act as magnifying glasses that amplify the sunlight shining in your eyes.

To safely observe the transit, look for solar filters that you can add to a telescope or binoculars, or look for telescopes or binoculars that already have the filters built in.

Webcasts and events

The astronomy streaming service Slooh, which provides live views of celestial events from telescopes around the world, will also stream live images of the transit. "Slooh will train its highly specialized Solar Telescope, based at its flagship observatory at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands, on the tiny planet Mercury as it crosses the face of the sun," according to the event description for the Slooh livestream, which viewers can tune into here beginning at 7:30 a.m. EST (12:30 GMT).

Another option for online observing is The Virtual Telescope Project. Viewers can tune in that broadcast here starting at 7:30 a.m. EST (12:30 UTC).

Places across the country like Evansville Museum in Indiana and the Willard Smith Planetarium in Washington state are also hosting live events.

The Amateur Astronomers Association of New York has also published details on its website about a citywide event, inviting viewers to access the association's safely filtered telescopes during Mercury's transit.

OFFER: Save up to 61% on 13 issues a year!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

- Shallow Craters on Moon and Mercury May Hide Thick Slabs of Water Ice

- BepiColombo: Joint Mission to Mercury

- Dramatic Drone Video Captures Magic of Total Solar Eclipse

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.