Shallow Craters on Moon and Mercury May Hide Thick Slabs of Water Ice

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Would-be moon explorers are eager to learn better tactics for tracking down ice, which they hope to turn into water and rocket fuel — and new research may have found a new key to spotting buried ice.

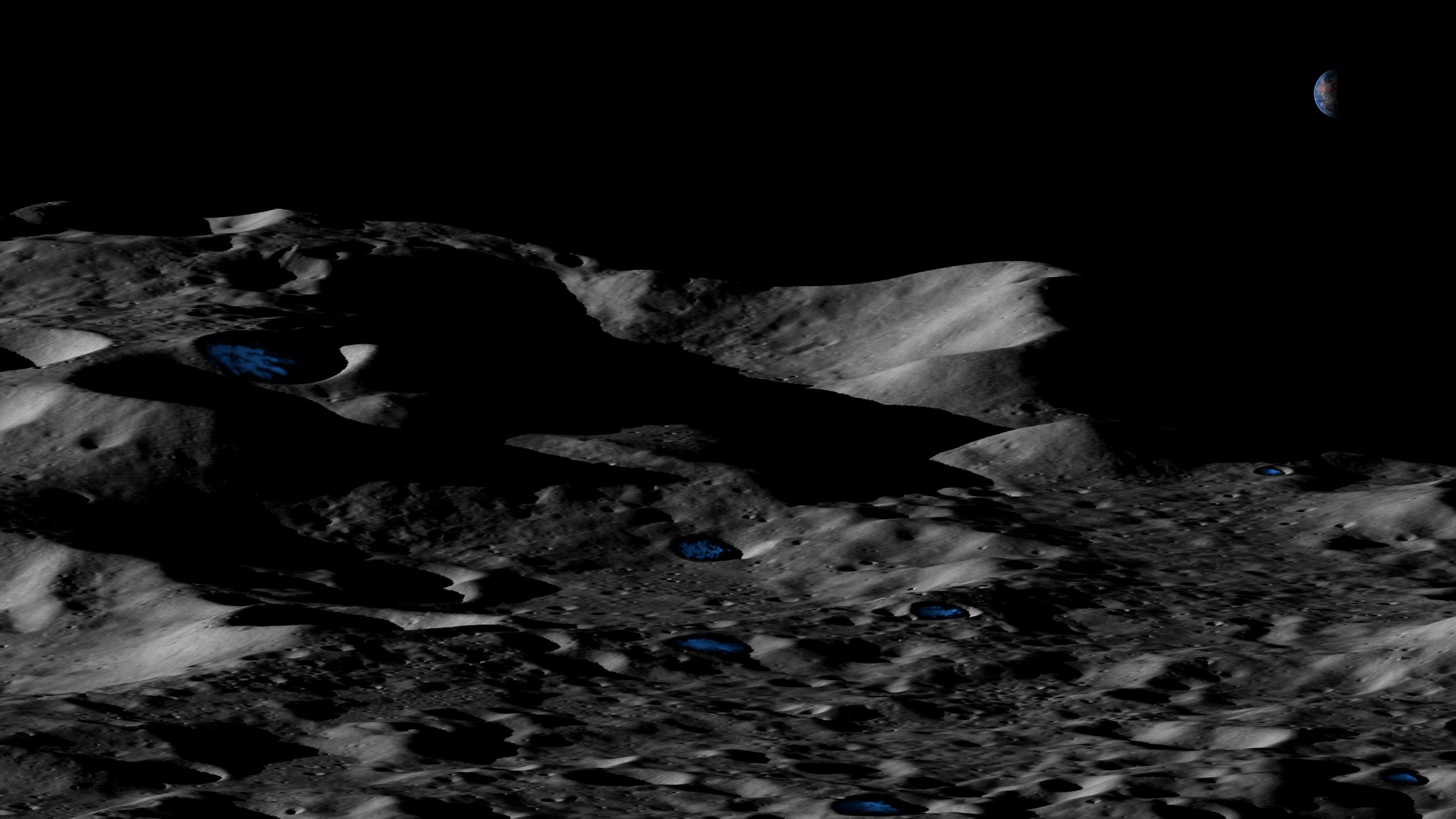

The research focused on both the moon and Mercury, the tiny innermost planet, and pulled together from two crucial NASA missions: the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter still circling the moon and the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) mission that ended its time at the planet in 2015. Scientists believe both bodies hide water ice near their poles, where the bottom of craters never see sunlight — and the ice lurking at the south pole of the moon is particularly intriguing.

"If confirmed, this potential reservoir of frozen water on the moon may be sufficiently massive to sustain long-term lunar exploration," Noah Petro, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Project Scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in a statement.

Related: Photos of Mercury from NASA's Messenger Spacecraft

All told, the scientists behind the new research looked at about 14,000 craters on the two small, gray bodies. Scientists have spotted thick deposits of water ice below the surface near the poles of Mercury. They're less confident that lunar ice is as slablike in structure — previous research has suggested the ice here is more mixed.

So the team decided to compare data between Mercury and the moon to try to better understand what the ice beneath the moon's poles might look like. By looking at more than 2,000 craters on Mercury, they realized that the craters that seem to hide thick slabs of ice also sport shallower sides than those that don't.

Then, the researchers turned their sights on the moon, and found that at the south pole, where previous researchers had identified buried ice, craters tend to be shallower. But that isn't the case at the moon's north pole, which also sports less water overall. The researchers think that combination may reflect a loss of ice near the north pole.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists' next intensive mission to Mercury, dubbed BepiColombo, is on its way but won't reach the tiny planet until 2025. But the moon, so convenient to Earth, will likely see new robots — and possibly even astronauts — touching down before BepiColombo's arrival. Such missions could help scientists decode the story of lunar water ice.

The research is described in a paper published July 22 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

- The 21 Most Marvelous Moon Missions of All Time

- Amazing Moon Photos from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Discovery of Water Ice on the Moon Thrills Lunar Scientists

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.