US planetary radar may get a boost from Green Bank Observatory

A trial run of a new planetary radar system caught this stunning image of the moon

It was serendipity that had scientists already toying with a demonstration of a new planetary radar system just as Earth lost its most powerful such instrument.

Well, serendipity and a fervent desire for more radar observations of everything from asteroids hanging around near Earth out to icy moons around the most distant planets. And the facility behind the experiment, the Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia, has enough of a history with planetary radar systems to want to take on a new role in the field. The result is a tantalizing new image of a historic spot on the most familiar solar system object of all, the moon. Scientists hope the image makes the case for permanently installing a much more powerful radar transmitter at the observatory's leading telescope, the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope.

"We got absolutely fantastic results," Karen O'Neil, director of the Green Bank Observatory site, said of the demonstration project during a panel discussion held Jan. 21. "Phase one was an absolute success and we were quite pleased with everything that's happened with that," O'Neil told the panel, which is focused on the science of small solar system objects like asteroids and which will inform the National Academies committee that is putting together the document that will shape planetary science priorities for the next decade.

Related: Losing Arecibo's giant dish leaves humans more vulnerable to space rocks, scientists say

The recent radar experiment was a decade in the making. And the facility's flagship radio telescope, the 300-foot (100 meters) dish has partnered with radar transmitters in Puerto Rico and California over the years. So why not go a step farther and create signals themselves?

"This is sort of a part of radio science that we've been involved in at some level for a long, long time," Tony Beasley, director of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, which built the telescope, told Space.com. "Starting back about 10 years ago, there was interest growing in thinking about what are some other roles and some other areas of radio science that Green Bank could get involved in, and so radar was an obvious candidate."

The case for radar

Radar astronomy occurs in two pieces: Scientists must first create the radio beam to bounce off the mystery object, then study the comparatively faint echo that returns, deciphering from it the object's surface, shape and location.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The steps can occur at the same radio dish as it rapidly converts between send and receive modes, or two radio facilities can team up, with one producing the radar beam and the other poised to gather the returning signal. When Green Bank began planning its demonstration project, it had never sent radar signals itself but had worked as a receiver for both of the major U.S. planetary radar transmitters.

At the time, there were two such transmitters: One at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico and one at NASA's Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex in California. But in December, the Arecibo radio telescope's science platform — including its transmitter — crashed down after cable failures at the facility, ending its tenure.

Planetary scientists will continue to feel that loss, even if the Green Bank project does turn into a full-fledged transmitter. The tentative Green Bank system isn't designed to replace Arecibo, since no one realized the Puerto Rican facility was nearing its end; instead, it was designed to collaborate with Arecibo and Goldstone alike.

"The program we've been developing was really built and designed in some way to complement the existing U.S. radar infrastructure," Beasley said. "Certainly the thing that we're talking about producing has some relevance to a post-Arecibo world, but in absolutely no way, this is not going to be a replacement for Arecibo."

And it's unclear whether the loss of Arecibo will influence the fate of the Green Bank project. The National Science Foundation (NSF), which owns both the Green Bank and Arecibo sites, plans to evaluate the project, acknowledging the recent loss but without scrambling to strengthen its radar capacity.

"If some capabilities are lost, there's always the question of where else would those capabilities come from? Is there something else that can continue something like that?" Harshal Gupta, NSF's program director for the Green Bank Observatory, told Space.com. "It's independent of what was going on at Arecibo. Now, given what has transpired, when it's fully developed, it might offer some of the capabilities that the planetary community might be able to use. But again, those two are two separate things."

Demo and design

The years of interest were there and the numbers looked promising. But before Green Bank committed to a full-fledged planetary radar project, astronomers wanted to test the waters. To do so, scientists built a miniature transmitter, powered at less than a kilowatt and about the size of a refrigerator, Beasley said, and in November hauled it up for a brief stint at the prime focus of Green Bank Telescope, suspended over the large dish.

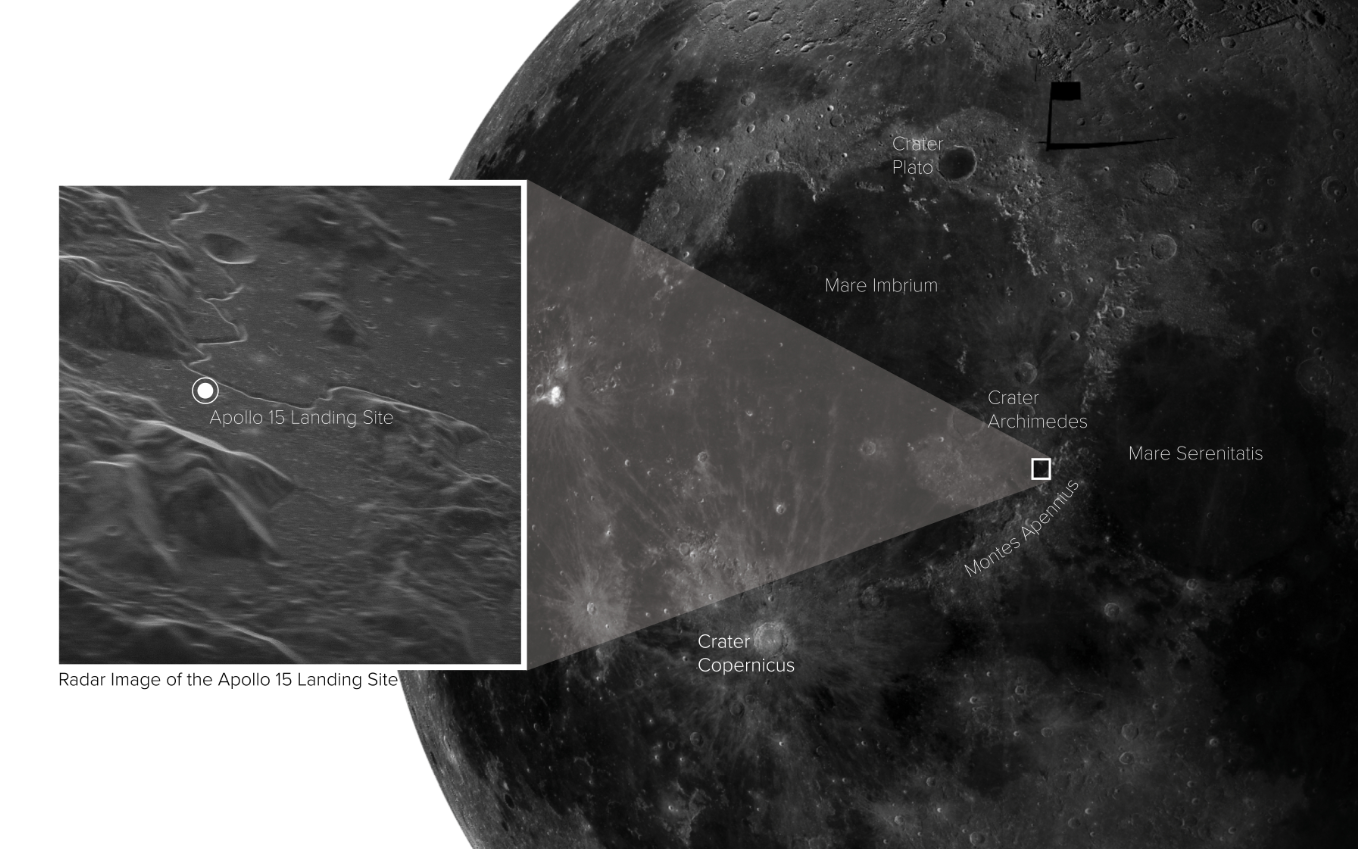

Then, the team took advantage of the telescope's superlative: It's the largest fully steerable radio telescope in the world, able to study objects across 85% of the sky. So the team pointed the telescope and fired the radar system at the moon — more specifically, at the Apollo 15 mission's landing site in the Hadley-Apennine region. The team used antennas of the NRAO's Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) to catch the signal that bounced back.

The image, with its sloping hills, stark crater and slinking rille, offers a hint of what could come. But the moon is our old companion. Scientists would much rather use a shiny new planetary radar system to study more mysterious objects, like the asteroids zipping through our neighborhood of the solar system, most of which are blurs and blobs, or the strange moons of the outer planets that have received few spacecraft visitors.

"Now we're just kind of thinking about what the next step is," Beasley said.

There are several options to weigh in deciding what a system would look like, Beasley and O'Neil both emphasized. The scientists suspect they'll stick with using a separate radio array to catch the returning signal, rather than housing that work at Green Bank Observatory as well. For now, that would be the VLBA, but if a next-generation Very Large Array comes to be, antennas from that system would be even more promising receivers, O'Neil said.

Two key factors that influence what precisely a radar system can do are the power of the transmitter and the specific frequency of the radio waves it produces. Green Bank is looking at a transmitter that would use tens or hundreds of times more power than the demonstration instrument and run at one of two frequencies. It's also looking to use a new transmitter technology, which would be more compact and, scientists hope, less persnickety to operate.

Given the design parameters scientists are currently considering, the system would be able to study objects in a much larger swath of the solar system than existing systems, including out to strange, icy moons. "You're increasing the volume that you're searching in the solar system by an order of magnitude," Beasley said. "It's a substantial increase, so we're very excited about the possibility there."

There are logistical concerns, of course, and these might be a key problem for Green Bank, which is a hugely popular instrument and already doesn't have time to conduct all the science researchers would wish for. Typically, the telescope has observed two or three objects per year through its radar partnerships with Arecibo and Goldstone; Beasley said that if the transmitter project becomes a reality, the facility might look to spend about a third of its time on radar.

All told, a full-fledged project would reshape planetary radar, the scientists said.

"The capabilities we're talking about are something that will be beyond anything we've been able to do in the past of planetary radar astronomy," O'Neil said. "We're talking about something that has some pretty amazing potential out there for planetary radar and really a system that has the ability to take us a leap forward, I would say, within the planetary radar capability of the United States. This is fun to think about and pretty amazing to talk about."

If the project continues and Green Bank installs a full-power radar transmitter, it would likely come online no earlier than perhaps 2024, depending on how quickly funding — likely "in the tens of millions of dollars," O'Neil said — comes together.

Gupta at the NSF said he was pleased to see the demonstration's success and looks forward to seeing what happens next at Green Bank.

"All indications are that there is great promise. Initial tests are great, and there's great potential," he said. "The big picture becomes more clear as science is done, as technology is developed. So I'll just say that: there are unanticipated advances, unanticipated opportunities. In the end, this would be exciting and we will see how it unfolds."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.