After Arecibo, NASA isn't sure what comes next for planetary radar

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Arecibo Observatory's massive radio telescope has collapsed; with it has gone a crucial tool in understanding asteroid risks to Earth — and it would take a serious government initiative to replace.

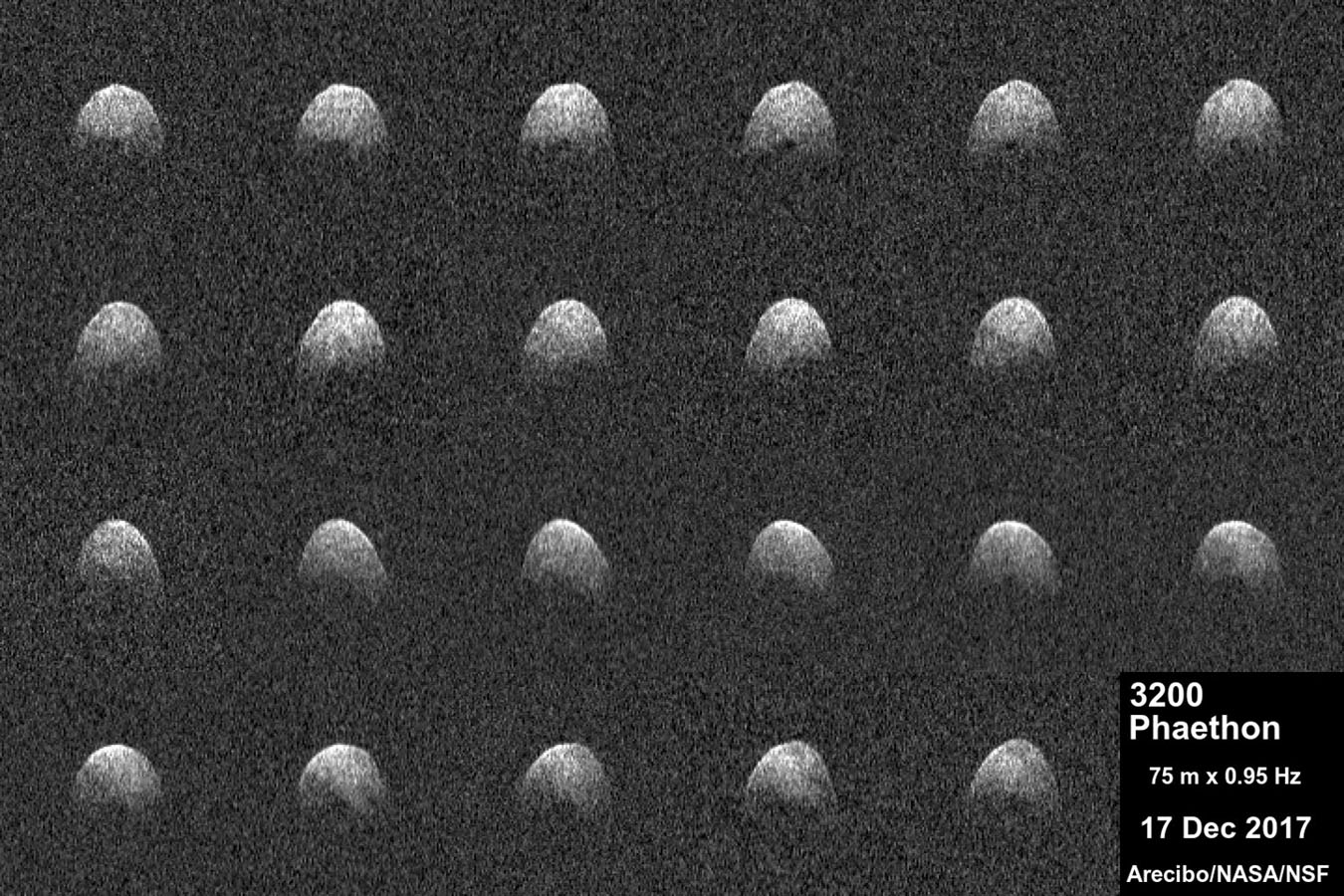

Before the facility sustained irreversible damage in a series of cable failures this year, Arecibo Observatory was Earth's most powerful planetary radar system. Astronomers can't use radar to discover new asteroids, but the data that these systems provide can give scientists the details about an object's size, shape and location they need to better and more quickly evaluate the threat that individual asteroids might pose to Earth.

"This is a hard thing to have to take [down] an iconic facility like this that's provided so much for the radio astronomy and planetary radar community over so many decades; it's really sad to see," Lindley Johnson, who leads NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office, said during a virtual meeting of NASA's Planetary Advisory Committee held on Nov. 30, the day before the structure collapsed. "It's certainly not an ideal situation, but I think it really comes down to, it's time to really get moving on investing in a new planetary radar capability."

Related: Losing Arecibo's giant dish leaves humans more vulnerable to space rocks, scientists say

But that's easier said than done. There are two key complications at play when it comes to investing in planetary radar capability.

One is bureaucratic: Planetary radar has to be done from Earth's surface. And while NASA leads the country's asteroid-focused work, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) heads the federal government's ground-based observations, as it does Arecibo Observatory; NASA merely paid for observation time on the radar system. With the sole exception of NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii, all of the agency's observing facilities are in space.

(This is also complicated. Technically, the world's other planetary radar facility, at Goldstone in California, is run by NASA, but that's because its primary duty is to communicate with spacecraft traversing the solar system. The radar facility recently completed an upgrade and is back to normal observations, although it has a less flexible schedule than Arecibo did and can't see objects as far from Earth.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: Losing Arecibo Observatory would create a hole that can't be filled, scientists say

"The way our agencies are tasked, ground-based observations are the responsibility of NSF," Lori Glaze, who leads NASA's Planetary Science Division, said during the same meeting. "It's not in NASA's purview."

A second complication is the cost. A radar beam as powerful as Arecibo's requires both a powerful transmitter and a massive radio dish, neither of which is cheap.

Taken together, the challenges mean that NASA would likely need to work out agreements with one or more government counterparts before a new planetary radar system comes online.

"This kind of thing really takes a partnership of agencies," Johnson said, adding that Arecibo itself traced its roots to a Department of Defense-led partnership. Something similar could rev up planetary radar, he said. "We do definitely have an opportunity and an interest in partnering with the U.S. Space Force on a more capable radar system." The military branch is interested in the technology as a way to track satellites between Earth and the moon, he added.

A reduction in planetary radar doesn't strike at the heart of NASA's planetary defense system, which focuses on discovering and tracking relatively large asteroids that come relatively close to Earth. Spotting such objects relies on facilities that detect optical and infrared light and scan large swaths of the sky regularly enough to notice when a new, fast-moving dot appears against the background of stars.

Radar can't do that; it requires that scientists have a good idea of precisely where the object they want to study is, so that they can point the narrow radar beam precisely enough to bounce off the object. Instead, planetary defense experts use radar to more quickly plot an object's orbit farther into the future and to determine characteristics of the object like its shape and density that might affect attempts to deflect an asteroid if it does appear to be on course to impact Earth.

"As far as planetary defense and NEO [near-Earth object] observations are concerned, it's only a slight negative impact," Johnson said of the loss of Arecibo's radar system. "It doesn't affect our discovery rate of near-Earth objects at all, it only has some impact on the opportunities we have to characterize these objects."

Nevertheless, radar data is nice to have — and definitely the sort of thing Johnson would want for the planetary defense community.

Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia was already planning to add radar capability to its primary radio dish before the loss of Arecibo, scientists say, although the system, like that at Goldstone, won't replicate Arecibo's specific skills. And even that new capability would build on an existing facility, rather than starting from scratch, which comes with both benefits and risks.

"In a perfect world, I would pursue a new planetary radar capability," Johnson said, even before Arecibo's final collapse. "Trying to keep these old facilities going — they are high maintenance."

But new capability wouldn't mean a copy of Arecibo's iconic dish, he emphasized. "It's really time to be looking at the next generation of planetary radar capabilities," he said, in particular hypothesizing that an array of dishes may be a more appealing approach now than Arecibo's single massive dish.

"Technology has moved on since the 30, 40 years ago that the radar capability was installed at Arecibo," Johnson said. "We need to take advantage."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.