Astronomers spot 1st moon-forming disk around an alien world

The disk has the potential to form numerous moons.

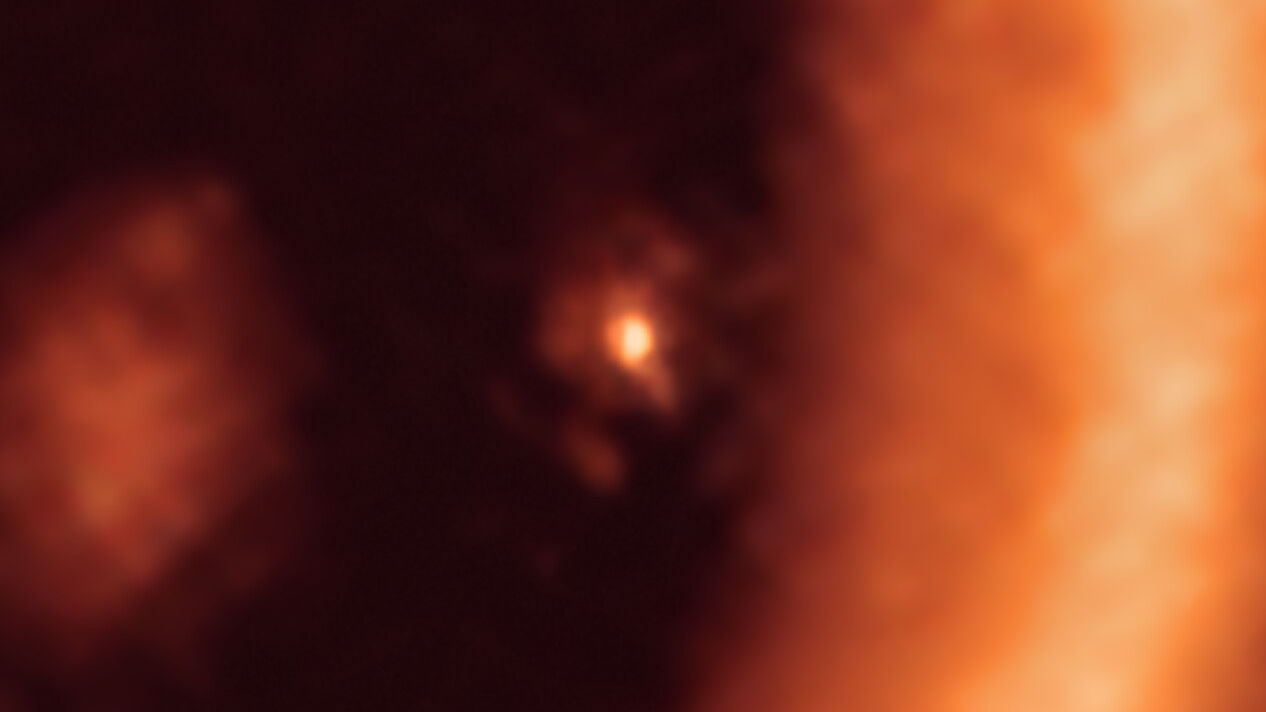

Astronomers have discovered the first disk surrounding a planet outside the solar system.

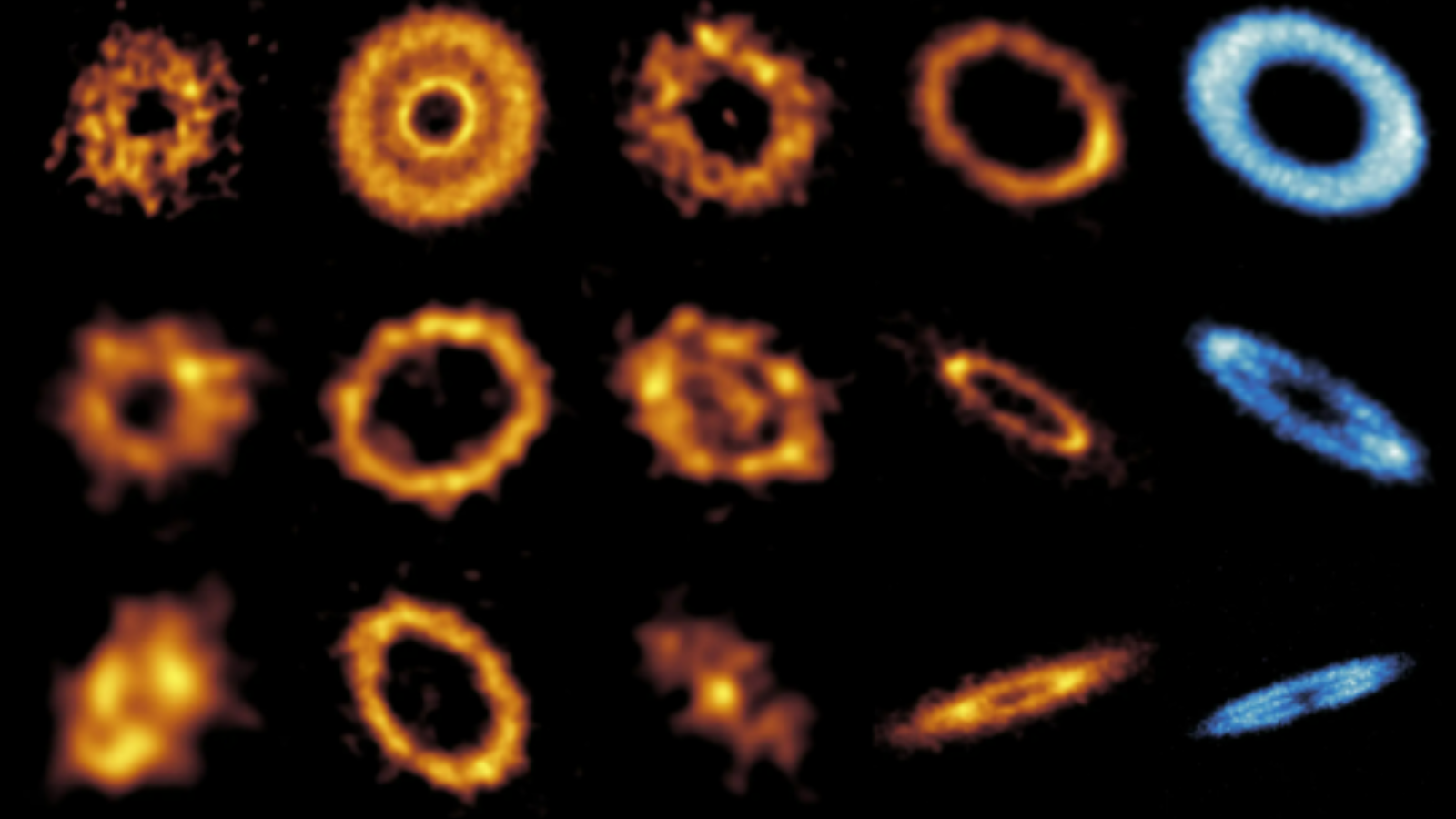

The impressive circumplanetary disk is about 500 times larger than Saturn's rings and encircles a Jupiter-like planet dubbed PDS 70c. Scientists have seen plenty of disks surrounding distant stars, and moon-forming disks around planets like this have been suspected before, but this is the first time such a system has been definitively identified, according to the researchers.

"Our work presents a clear detection of a disk in which satellites could be forming," Myriam Benisty, study lead author, an astronomer at the University of Grenoble and the University of Chile said in a statement.

Related: With all these planets, why haven't we found any exomoons?

PDS 70c is one of two young gas giants located approximately 400 light-years away from Earth. This world and its counterpart, PDS 70b, are still in the early stages of formation and provide a unique research opportunity to study planets and moons in their infancy.

"More than 4,000 exoplanets have been found until now, but all of them were detected in mature systems," Miriam Keppler, study co-author and researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy said in the same statement. Not so for the two planets observed by the current research. "PDS 70b and PDS 70c, which form a system reminiscent of the Jupiter-Saturn pair, are the only two exoplanets detected so far that are still in the process of being formed."

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), based at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in the Atacama desert of northern Chile, scientists were able to measure the diameter of the disk to be roughly the same as the distance between Earth and the sun (1 astronomical unit, or approximately 92,955,807 miles or 149,597,870 kilometers). The researchers also found that the disk contained enough material to form up to three satellites about the size of Earth's moon.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Unlike its companion, PDS 70b is disk-less. The high resolution ALMA observations indicate that the PDS 70b was probably starved of disk-building dust by PDS 70c during their early formation.

"These new observations are also extremely important to prove theories of planet formation that could not be tested until now," Jaehan Bae, a co-author and an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science, said in the same statement.

Scientists theorize that planets establish themselves in dusty disks around young stars, clearing a path through their orbit and gorging on material as they go. As a planet grows it can then form its own circumplanetary disk that continues to feed the young planet with gas and dust. Within that disk, the gas and dust particles also collide and can form increasingly larger bodies, eventually resulting in the birth of moons. However, astronomers have yet to fully understand and witness these processes.

"In short, it is still unclear when, where, and how planets and moons form," Stefano Facchini, an astrophysics research fellow at ESO and co-author on the research said in the same statement. The latest observations of PDS 70b and PDS 70c are helping shed light on such formation processes.

The researchers hope to be able to revisit the pair using ESO's Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), which is currently being built on Cerro Armazones, a peak in the Chilean Atacama Desert.

"The ELT will be key for this research since, with its much higher resolution, we will be able to map the system in great detail," Richard Teague, study co-author and a fellow at the Center for Astrophysics at Harvard and the Smithsonian.

The research is described in a new study published July 22 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!