Eclipse season 2020 has arrived! Catch 2 lunar eclipses and a 'ring of fire' this summer

During June and early July, it is eclipse season once again. In the coming weeks, there will be three eclipses that take place: one of the sun and two of the moon.

But none of these events will be visible (or in one case, readily evident) from North America; the two lunar eclipses will hardly be noticed, if at all. Only the solar eclipse will be worthwhile to journey to if you wish to see it. Sadly, however, because of travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it's not likely anyone will be able to attempt a pilgrimage to see it.

In order to have an eclipse of the sun or moon, our natural satellite must be positioned almost directly in line with the sun and Earth. A lunar eclipse takes place when the moon is at full phase and passes into the shadow of the Earth. A solar eclipse happens when the moon is at new phase and crosses between the Earth and the sun. But while the new moon and the full moon are moon phases that recur each month, eclipses at these phases can only happen at two opposite seasons per year.

Related: How to catch the next eclipse: A list of solar and lunar eclipses in 2020 and beyond

Moon's orbit slightly out of whack with Earth

In order for the moon to be eclipsed by the Earth's shadow, or to eclipse the sun, it must be directly (or very nearly so) in alignment with the sun and Earth. But more often than not, this does not happen at every full or new moon because the moon's orbit around the Earth is slightly out of kilter with the Earth's orbital plane around the sun. To be more precise, the moon's orbit is tilted, or inclined 5 degrees to that of the Earth's. As a result, in most cases, the moon will pass above or below the sun at new moon phase and above or below the Earth's shadow when it's full.

But at two points along the Earth's orbit, the orbital planes of the Earth and moon coincide; such a point is called a "node." The point where the moon's orbit crosses the Earth's orbital plane going from south to north is called the ascending node and when it is crossing from north to south it's called the descending node. And if the moon happens to be at new or full phase when it arrives near a node, then an eclipse becomes possible.

We don't need to have the moon arrive precisely at the node in order for an eclipse to happen. For it to eclipse the sun, the new moon must be within about 18.5 degrees of a node, at most, in order for a solar eclipse to take place. For a lunar eclipse, the full moon must be, at most, 12.25 degrees of a node in order for it pass into the Earth's shadow. The closer the moon is to a node, the more "central" (or total) the eclipse will be. If the moon is far from the node, then the resultant eclipse will only be partial.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Eclipse seasons are slightly less than six months apart, and each season lasts for a little over a month. In 2020, the middle times of the two seasons come in June and December. And these nodes are not stationary points at all, they move or "regress." As such they come about 19 days earlier each year, making an eclipse year — the interval between two successive returns of the sun to the name node of the moon's path — 346.6 days.

Let's take a look at this seasons three eclipses, starting with the most important one, that of the sun.

A "hairline" ring of fire

There will be a new moon occurring on June 21 at 2:41 a.m. EDT (0641 GMT), and just 2 hours and 19 minutes earlier, the moon will arrive at the ascending node of its orbit, assuring that it will eclipse the sun.

And because the moon was at apogee — its farthest point from Earth — just six days earlier and is situated at a distance of 241,000 miles (387,900 kilometers) from Earth, the dark shadow cone of the moon (the umbra) fails to make contact with the Earth, and as a result its disk will appear ever-so-slightly smaller than the sun.

As such, when the moon passes squarely in front of the sun, it will not totally cover it, but instead a narrow ring of sunlight will remain visible. Hence, the term "annular" eclipse, derived from the Latin "annulus" meaning ring-shaped. A fitting analogy is placing a penny atop a nickel; the penny represents the moon and the nickel is the sun.

Related: Solar eclipse guide 2020: When, where & how to see them

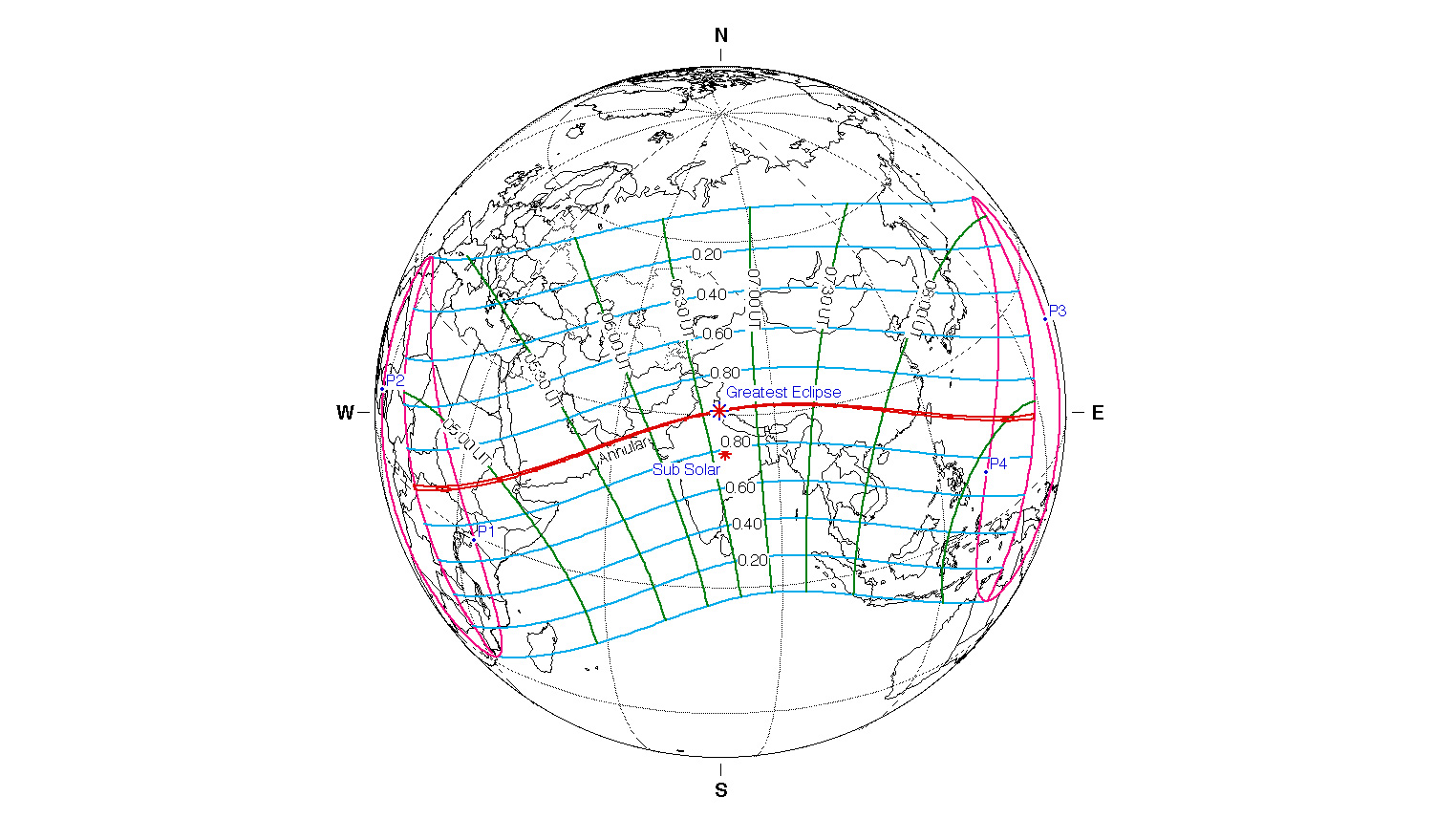

The eclipse path — which makes the shape of a bow about to shoot an arrow north — starts in central Africa at sunrise in the Republic of the Congo, just west of the Ubangi River. Then it moves northeast cutting through parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Sudan, Ethiopia, the Red Sea, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Oman, the Gulf of Oman, Pakistan and India. Then it turns east and finally southeast over China, Taiwan and then out into the Philippine Sea, passing just south of Guam before coming to an end at sunset over the North Pacific Ocean.

The point of greatest eclipse will occur over Uttarakhand, a state in northern India crossed by the Himalayas. At this particular point, the tip of the moon's umbra ends roughly 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from the Earth's surface. So the moon comes very near to fitting completely over the sun: the magnitude of the eclipse is 0.994, which means that the bright ring left around the moon's silhouette measures just a mere six-tenths of a percent of the sun's width, resulting in a hairline ring of light. So close to registering as a total eclipse, and yet, so far!

The path width will have shrunk to just 13 miles (21 km) and the ring phase will last just 38 seconds. A partial eclipse of varying extent will be visible over much of Africa and Asia, as well as Indonesia. A slice of southeast Europe will catch the opening stages of the eclipse after sunrise and a small section of northernmost Australia will catch the end just prior to sunset.

The underwhelming lunar eclipses

Usually in the case of an eclipse season there are two eclipses — one of the sun and one of the moon. But this is a special case, resulting in three eclipses. The reason is that its central one — the annular eclipse of June 21 — is very central; very near the theoretical middle of the season. So, we can squeeze two lunar eclipses in, one coming two weeks before and the other two weeks after the solar one. But these two flanking events nearly miss being eclipses at all.

The first of these comes on June 5, when the moon barely encounters the Earth's outer penumbral shadow because it still has nearly a full day to travel before reaching its descending node. Less than six-tenths of the moon's diameter will penetrate the penumbra.

Related: Lunar eclipse 2020 guide: When, where & how to see them

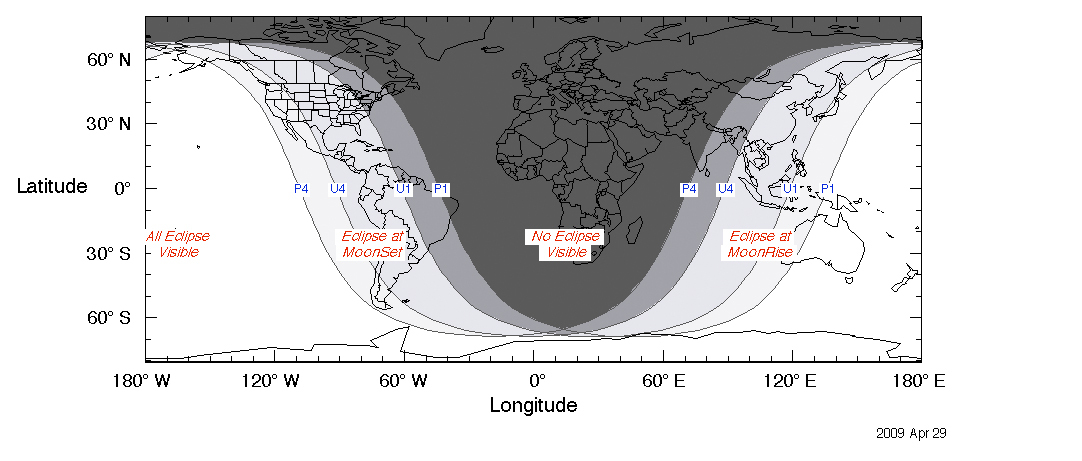

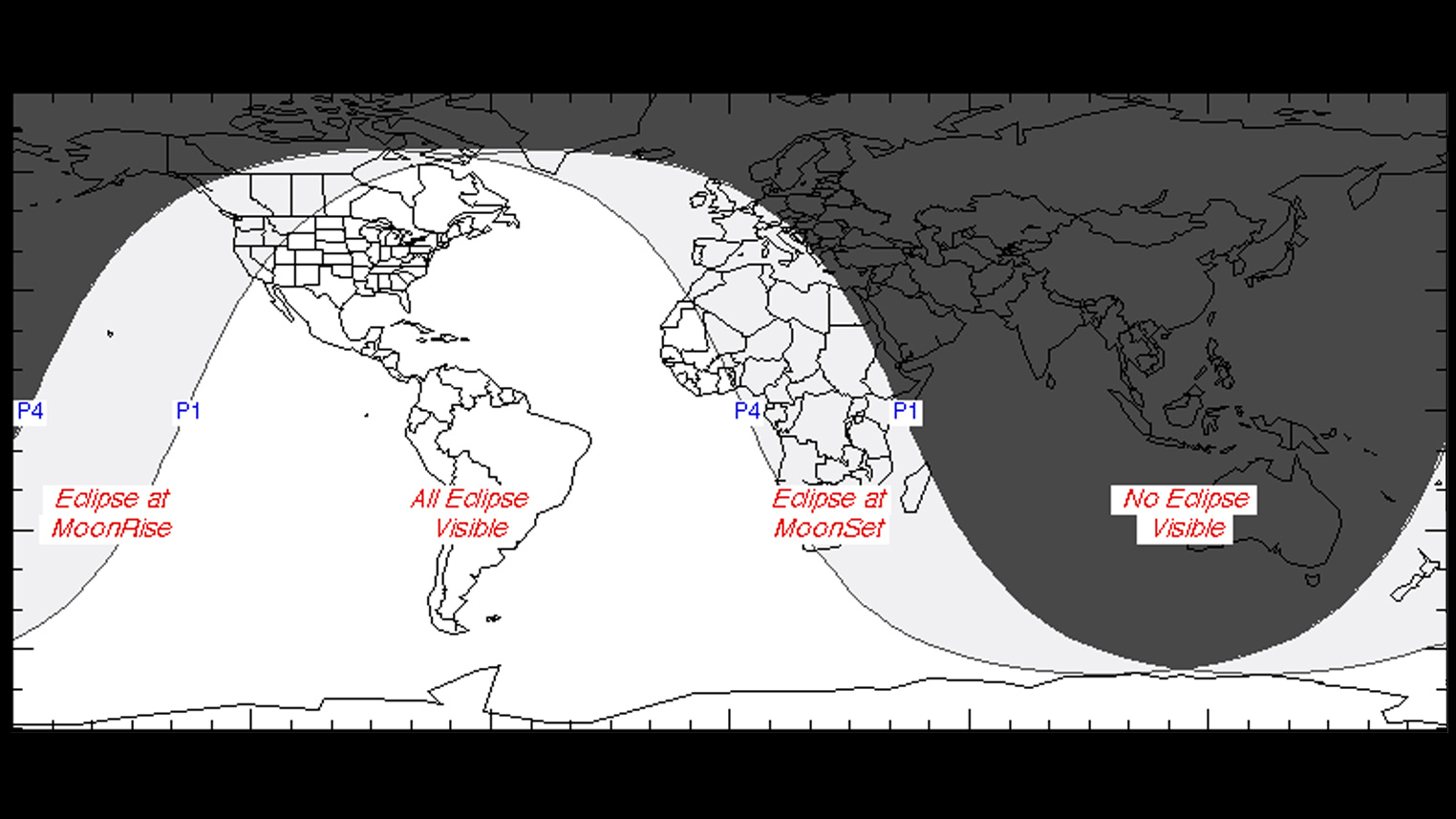

Generally speaking most people would not notice a darkening or shading effect if less than seven-tenths of the moon's diameter were inside the penumbra, so it's debatable whether anyone will notice any slight darkening effect on the moon's lower edge at mid-eclipse. Visibility will be confined to central and east Africa, Eastern Europe, western and central Asia, most of Indonesia and Australia.

The other lunar eclipse flanking the June 21 central solar one is even more marginal and results in basically a non-event late on the night of July 4-5. Less than fourth-tenths of the moon will slide through the southern edge of the Earth's penumbra — not enough to create any kind of noticeable darkening on the moon's disk. Too bad, because Central and Eastern portions of North America will be turned toward the Moon during this underwhelming eclipse.

Coming attractions

At the next eclipse season, which will encompass the months of November and December, we will have another penumbral lunar eclipse on Nov. 30 and a total solar eclipse that will cut through southern portions of Chile and Argentina on Dec. 14.

- Wolf Moon lunar eclipse kicks off penumbral quartet for 2020 (photos)

- The 8 most famous solar eclipses in history

- How lunar eclipses work (infographic)

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.