A 'Pale Green Dot': Why Proxima Centauri b May Have a Shiny Tint

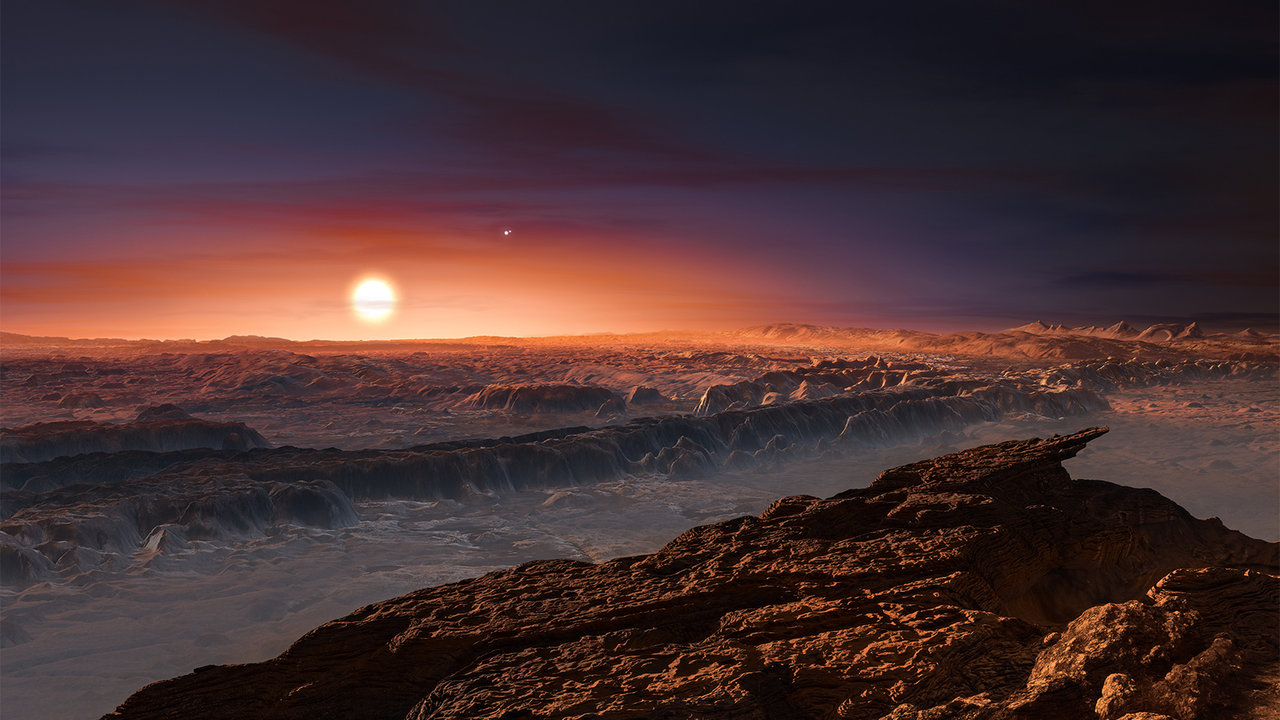

A world orbiting the sun's closest stellar neighbor may have a shiny green tint to it — and not necessarily because it's covered in leafy plants.

Researchers have found a way to characterize potential auroras on the nearby exoplanet Proxima Centauri b and found that, if the planet sports oxygen in its atmosphere, the auroras may give the atmosphere a greenish cast.

"The northern and southern lights [on Proxima Centauri b] would be at least 100 times brighter than on Earth," Rodrigo Luger, a postdoctoral student at the University of Washington, who led the study of how the planet's auroras could be spotted from Earth, told Space.com by email. Luger said the auroras might be so bright as to be visible with very powerful telescopes. [Proxima b By the Numbers: Possibly Earth-Like World at the Next Star Over]

Pale Green Dot

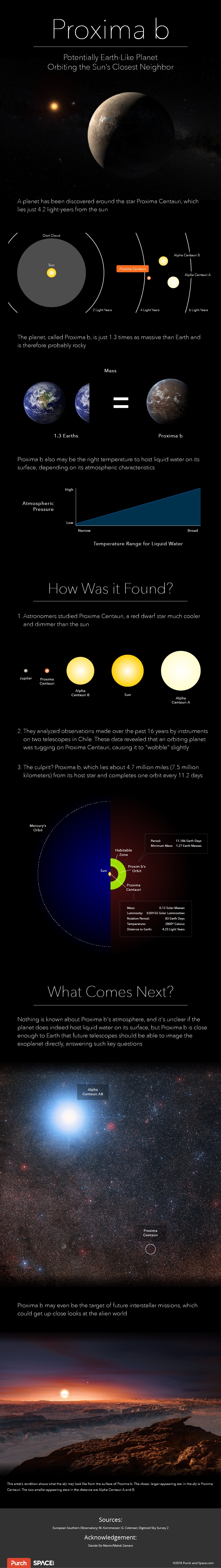

The active star Proxima Centauri lies only 4.2 light-years from the solar system. A small world orbits in the star's habitable zone, the region where liquid water could survive on the surface. Its radius remains a mystery. However, scientists know it is about 1.3 times as massive as the Earth, which its initial discovers said suggests a rocky planet.

Proxima Centauri is a small star, dimmer than Earth's sun, so its habitable zone is closer to the star than the habitable zone of the sun. As a result, Proxima Centauri b is 20 times closer to its star than Earth is to the sun, and completes an orbit every 11.2 Earth-days. The red dwarf star is more active than Earth's sun, firing off far more frequent flares that may douse the planet in radiation that could be harmful for potential life.

Those same flares may help scientists better understand the planet. If Proxima Centauri b has a magnetic field, it may capture the charged particles in the flares and funnel them toward the poles, creating brilliant auroral displays.

Observing the auroras can help researchers characterize the planet's atmosphere. On Earth, the different color glow of the northern and southern lights corresponds to reactions with different molecules in the atmosphere. According to Luger, who presented the results at the Astrobiology Science Conference in Mesa, Arizona, in April, if Proxima Centauri b is a terrestrial world with an Earth-like atmosphere and a magnetic field, the green light of the oxygen auroras would grow 100 times stronger than on Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Because of the potential for green light, the researchers dubbed such a world "the pale green dot," a nod to Carl Sagan's categorization of Earth as a pale blue dot.

Periods of intense stellar activity could make the auroras even brighter. While coronal mass ejections and flares have the strongest impact on generating auroras, Luger said, they aren't really predictable in advance.

"But the sun certainly has periodic activity cycles, so if we understand those of Proxima Centauri, we might be able to use that to our advantage," he said.

He went on to say that the extreme activity of the star may make such knowledge unnecessary — astronomers could simply count on a high likelihood that the star would flare and cause the auroras to brighten.

Optimal for auroras

While several studies have described searches for auroras on gas giant exoplanets that orbit close to their parent stars, none have been spotted on worlds beyond the solar system. But Luger remains confident.

"Proxima Centauri b is optimal for auroral detection," he said.

He gave several reasons that auroras may be soon spotted on Proxima Centauri b. The planet is nearby — it's the closest known exoplanet to Earth — making it easier for instruments to collect detailed observations. The extreme magnetic activity of the star, coupled with the planet's close orbit, means Proxima Centauri b is bombarded with solar particles far more vigorously than Earth. At the same time, the star is faint, so a glowing green planet would show up more easily than it would around a sun-like star. Finally, the short orbit means that the world moves around its sun at a rapid clip; when a light source is moving toward or away from an observer, this motion can be observed through a phenomenon called redshift, or Doppler shift. Luger said the Doppler shift of the auroras' light waves would be significantly larger than they would be on their own, making lines that would otherwise be hard to see more visible. That would make it easier to identify any oxygen in the atmosphere.

Unfortunately, this "pale green dot" won't be spotted with current telescopes. NASA's upcoming powerhouse telescope ― the James Webb Space Telescope ― will hunt for infrared light, so Luger said it won't be able to detect the green oxygen aurora, which is in the visible light range.

"Our best bet for detection is the [Thirty-Meter Telescope] or similar next-generation extremely large telescopes," he said.

The Thirty-Meter Telescope (TMT) — so-named because its primary mirror would be 30 meters (98 feet) wide — began construction on Hawaii's Mauna Kea peak before it was halted in 2015 after protests over the sacred nature of the land. The project remains at a halt today, though some astronomers have lauded the benefits of moving the telescope to Spain's Canary Islands.

But even TMT would take some time to identify the signature of oxygen from the auroras, with Luger estimating "tens of hours" of observation. The same is true for the Large UV/Opitcal/Infrared Survey (LUVOIR), a proposed design for a telescope with a primary mirror between 9 and 15 meters (30 and 50 feet). With telescope time extremely competitive, it could be hard to study the system so extensively.

In order to produce auroras, a planet must have a magnetic field. Out of the four terrestrial planets in Earth's solar system, only two have a worldwide field — Earth and Mercury. Mars has a patchy field, and Venus has none. If Proxima Centauri b is similarly lacking, it might not produce auroras.

However, the planet may get a brightness boost from airglow, the faint emission of light from the atmosphere that keeps nighttime on Earth from ever being completely dark.

"The planet is likely also to have strong airglow, which is planetwide," Luger said. "Airglow is not generated by magnetic fields, and is typically weaker than aurorae, so we did not calculate it. But it should be quite strong on Proxima Centauri b, and could cause the entire planet to glow green."

The research was published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook, or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky