Sky-Charting Mobile Apps Can Be Your Astronomical Time Machine

Astronomy sky-charting apps such as SkySafari 5, Starwalk 2 and Stellarium Mobile are terrific for showing you what's in your sky every night, but did you know that you also hold an astronomical time machine in the palm of your hand?

By manually setting the app's location, date and time, you can see the sky from anywhere on the planet at virtually any point in human history. Would you like to see what Galilieo saw with the first astronomical telescope way back in 1610? Perhaps you are curious how the moon looked from your house when Neil Armstrong took his first steps on our natural satellite — and how we looked to him!

In this edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll take a trip through time and explore some of the great moments in astronomical history. [14 Best Skywatching Events of 2017]

Manually setting the location, date and time

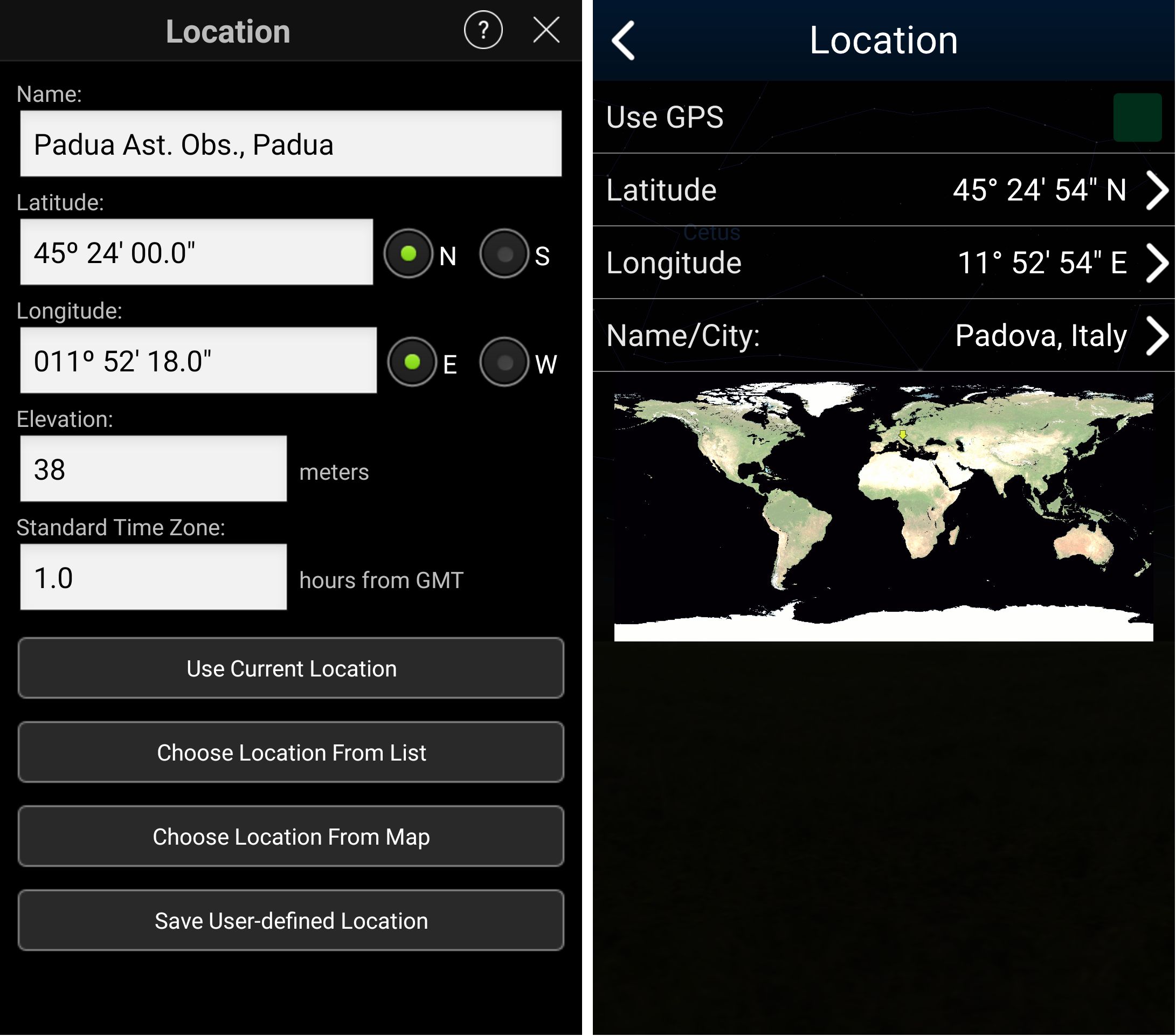

By default, your astronomy app will use the location provided to it by your device. When launched, some apps display the sky for the current time (SkySafari 5), others sunset that day (Starwalk 2 and Stellarium Mobile, by default). All the better apps allow the user to manually override these settings.

The SkySafari 5 app's Settings menu has a Location option. Here you can enter everything manually (including time zone), choose a location from a list of countries and their major cities, or drop a pin on a zoomable map of the world. For skywatchers who use the app in multiple places, such as home, vacation property and personal observatory, the app lets you save them to a list of user-defined locations. The Use Current Location button returns to your current location — handy after the world traveling we'll be doing below.

The Starwalk 2 app offers an alphabetical list of major world cities and a current location option. Stellarium Mobile requires you to toggle off the Use GPS setting before you can type in the latitude and longitude, tap on a world map, or select a country/city combination. Remember that for most purposes, the location doesn't need to be too precise — within 60 miles (100 kilometers) is good enough.

The SkySafai 5 app offers two ways to change the date and time. Tapping the Date & Time option under settings brings up a screen where you can manually type in the year-month-day-hour-minute-second, which is the easiest way to dial in a specific point in history. You can also select from Sunset, Sunrise, Moonset, Moonrise, Dusk End and Dawn Start on the chosen day. A Now button returns the app to the present. In the sky-viewing mode, a tap on the Time icon opens the time flow controls where time can be stepped in increments or flowed forward and backward continuously.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Stellarium Mobile's Date and Time selection is similar — you can increment via arrow buttons, or type new values over the existing ones. It only provides a Now button. To set the date and time in Starwalk 2, you tap the clock icon on the main screen and then tap again to highlight the unit to be adjusted (year, month, day, hour and minute). A scale appears along the right edge of the screen: slide it up to go forward in time and down to go backward. It will keep flowing until you hold it steady. This system makes it challenging to jump between historical dates, but it can be done.

Other sky-charting apps should work in a similar way. Don't forget to revert to the present moment after you've finished time traveling. Now let's look at a few interesting events you can re-create on your device.

What Galileo saw

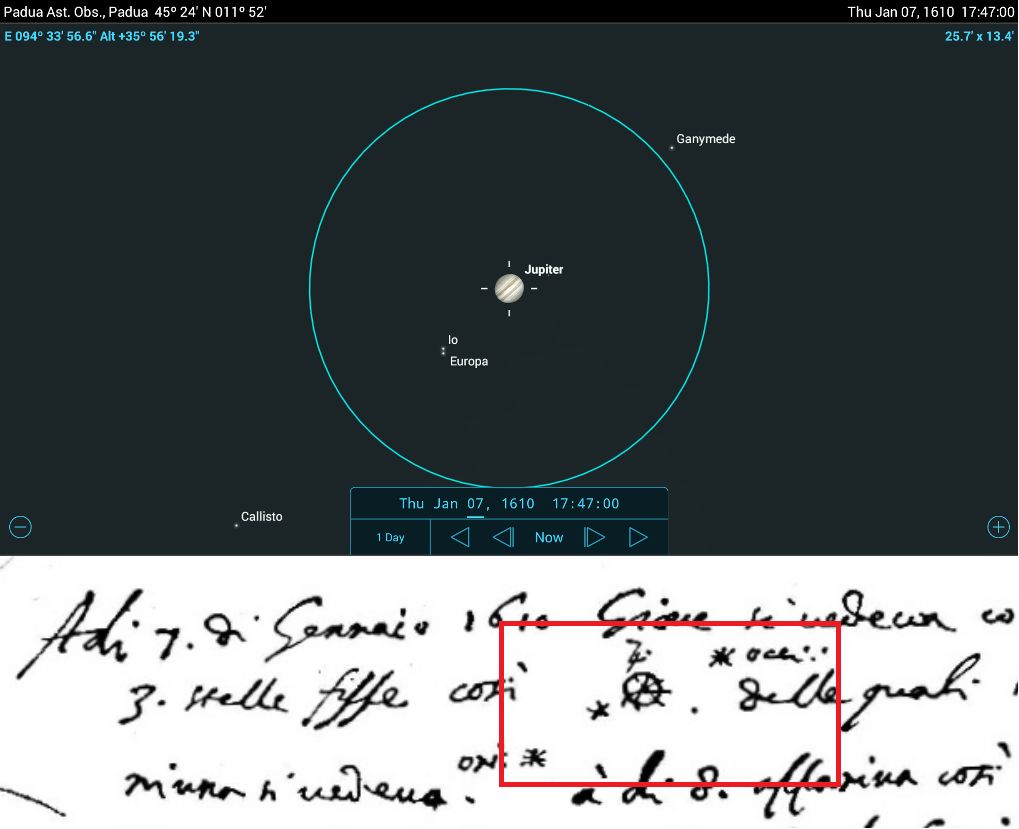

On Jan. 7, 1610, Italian scientist Galileo Galilei launched the era of telescope astronomy when he turned his newly made spyglass toward Jupiter. The instrument was crude by today's standards. According to the Galileo Museum in Florence, where the original resides, the aperture was only 2 inches (51 mm) across, and the magnification was a mere 14x, slightly stronger than 10x50 binoculars. Unlike binoculars, which typically cover 5 degrees of sky, Galileo's telescope generated an image covering only 0.25 degrees. By moving his eye around, he could increase this by a factor of two or three.

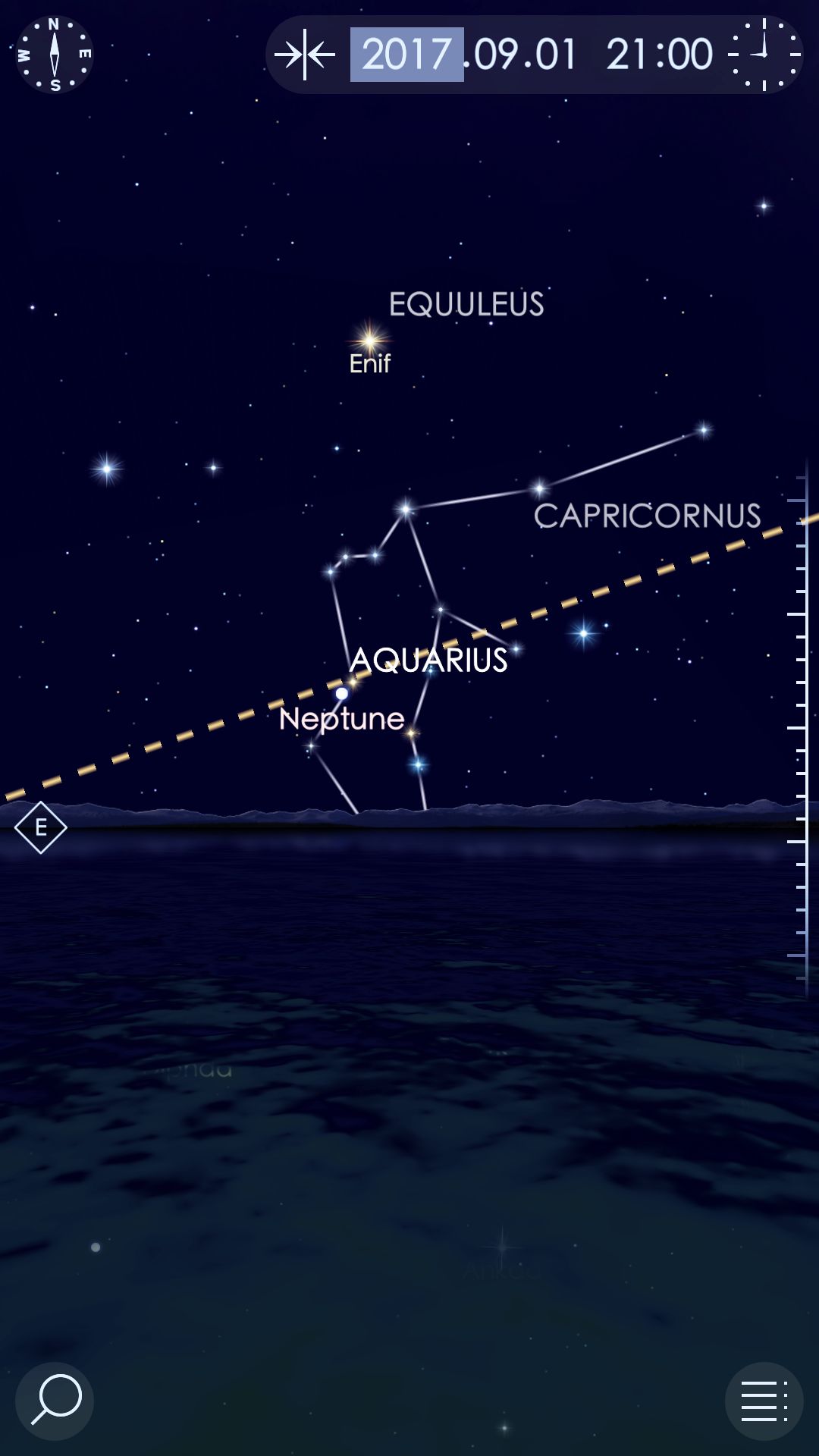

About an hour after sunset in Padua, Italy, from where he was observing, Galileo examined Jupiter. Astronomers of the day knew that Jupiter was a planet and that it traveled the ecliptic, the imaginary circle around the sky that defines the plane of our solar system. To his surprise, he noted that three small "stars" sat close to Jupiter, two on the left (east) of the planet and one to the right (west). All were positioned in a straight line that passed through the planet and aligned with the ecliptic. He sketched them. The next evening, he looked again and saw that three stars were now all on the right of Jupiter, despite the fact that Jupiter was known to be shifting westward through the distant stars in a retrograde motion loop. He concluded that the stars were accompanying Jupiter, but wondered about the relative position change.

We now know that Galileo was seeing the dance of the four largest moons of Jupiter — much later named Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. On every clear night thereafter, he observed and sketched the grouping. On some evenings, only two "stars" appeared. His telescope was not powerful enough to resolve moons that were spaced close to one another, and he wouldn't have known that the moons could disappear behind the planet or disappear as they crossed in front of it. You can see scans of Galileo's original notes, written in Latin, here while translations are here. It's fascinating to read his thoughts. [Photos: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter]

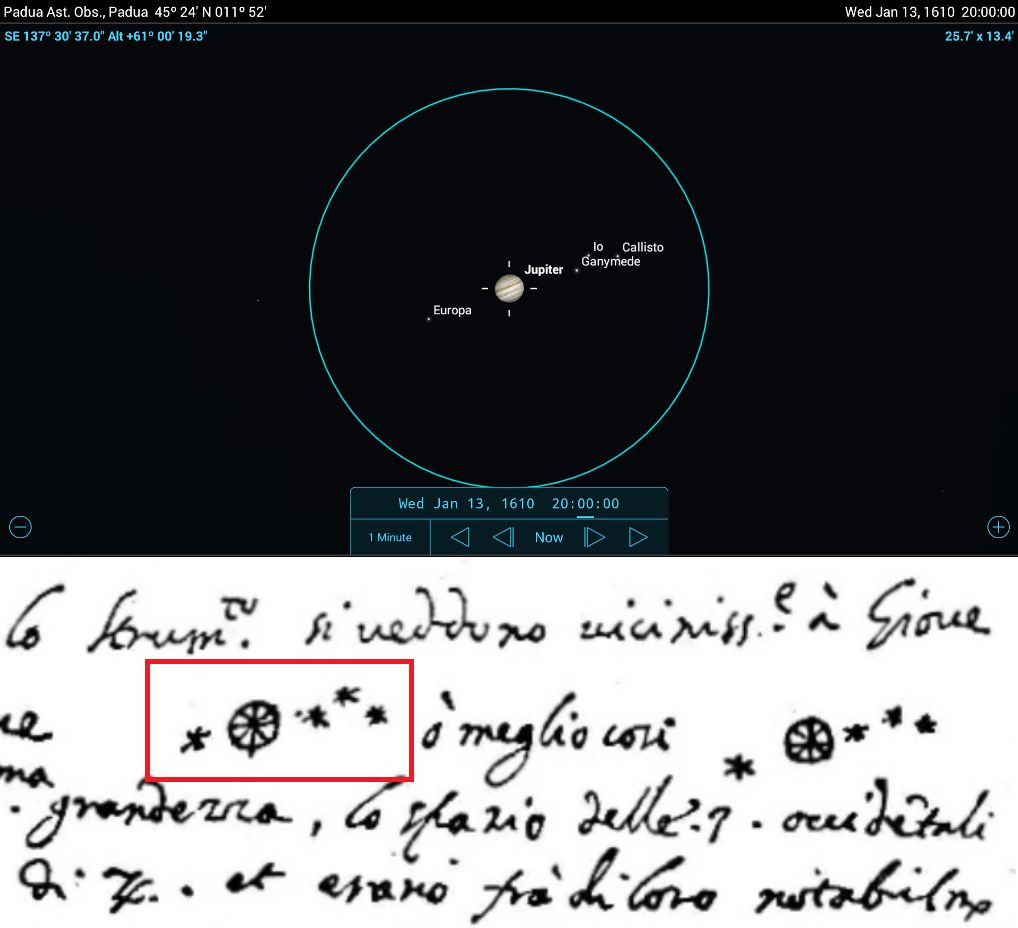

On Jan. 13, 1610, Galileo finally sketched all four moons. By systematically tracking the arrangement for several months, he eventually concluded that Jupiter has four natural satellites orbiting around it. This was controversial, since doctrine held that the Earth was the center of everything in the heavens.

You can re-create Galileo's journey of discovery in your app. Set the app's location to anywhere in Padua, and set the time to about 6 p.m. on Jan. 7, 1610. Then find and center Jupiter and zoom in until the disk of the planet and the moons are visible. If you enable the display of the ecliptic line (it's under Grid and Reference settings in SkySafari 5), you will see that it slopes to the upper right. Jupiter is below the ecliptic due to its small orbital inclination.

On Jan. 7, you'll see that Io and Europa together made one "star." All but Callisto jump to the west the following evening. But Galileo didn't expect four "stars," so lonely Callisto wasn't drawn. On Jan. 9, it was cloudy in Padua. On Jan. 10, he sketched two "stars," lumping Ganymede and Europa together and missing Io tucked against the planet. On Jan. 11, he saw Callisto and Ganymede, but Io and Europa were too close to Jupiter. On Jan. 12, Galileo either grouped Io and Callisto together, or observed later in the evening when Callisto was near Jupiter (advance the time by hourly steps to see this). On Jan. 13, Galileo finally sketched all four moons. For the next few months, he carefully noted how they moved and worked out that some orbited Jupiter closer and faster (Io) and others farther and slower (Callisto).

As a fun exercise, next time you train binoculars on Jupiter, see if you can see the moons, then check your observations against your app. By the way, Galileo's small telescope was too small to see Jupiter's Great Red Spot. That didn't occur until Giovanni Cassini described it in 1665, after telescopes had improved.

When you are finished playing Galileo, zoom the app's display out a little. Jupiter was passing through the zodiac constellation of Taurus at the time. A nearly full moon rose at 8:22 p.m. on Jan. 7, offering another celestial target for Galileo. And unbeknown to him, the blue-green planet Uranus was sitting only 2.5 degrees to the upper right of Jupiter. It wasn't discovered until years later — and it's quite a story.

A walk on the moon

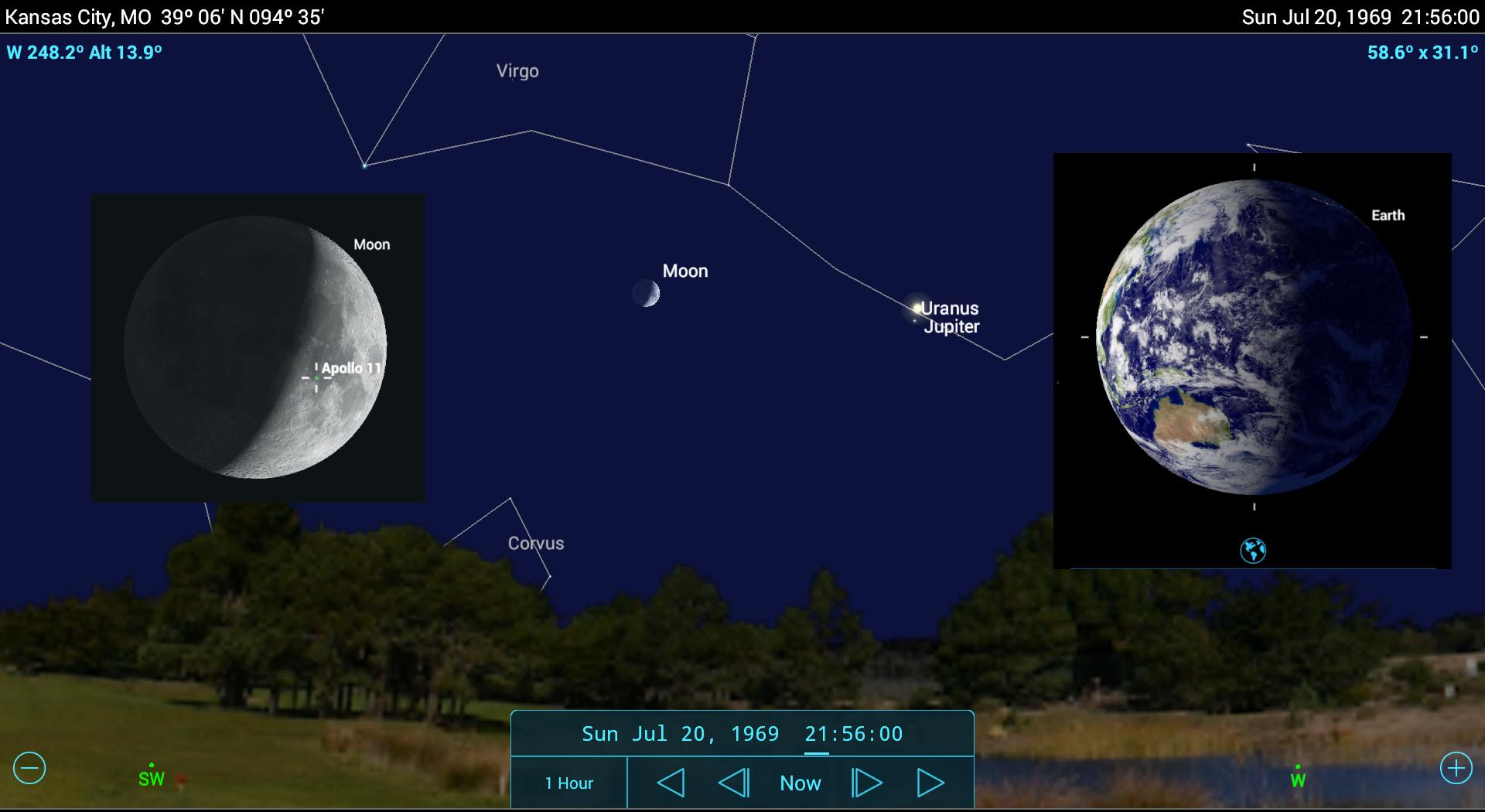

Where were you at 10:56 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time on July 20, 1969? Those of us of a certain age were glued to our sofas, watching Neil Armstrong take the first steps by a human being on another world, our moon. If you had looked outside, you'd have seen a lovely waxing crescent moon, about a day and a half shy of first quarter. For eastern North Americans, the moon was getting ready to set, only a few degrees above the horizon. On the West Coast, the moon was about halfway up the southwestern sky in bright twilight, with bright Jupiter sitting a generous fist diameter to the moon's right.

You can re-create the scene yourself. Use your home location and set the date to July 20, 1969. Next, you need to know the local time equivalent of 10:56 p.m. EDT. Subtract 1 hour for each time zone west you are (i.e., 9:56 p.m. Central, 8:56 p.m. Mountain and 7:56 p.m. Pacific). Now search for and center the moon. If it's not visible, it may have set or be hidden by the app's ground panorama. To remedy this, you can switch to a flat horizon under settings.

Where was Apollo 11 on the moon? If your app allows it, enable the display of surface features. In SkySafari 5, it's the Surface Labels option in the settings menu under Solar System. Or, you can simply use the Search menu and enter "Apollo 11," then center it. You'll see that the astronauts were in the lit portion of the moon, on the southern edge of the Sea of Tranquility. The other Apollo missions can be searched, too.

Finally, let's see what Neil Armstrong saw when he looked back at Earth. In SkySafari 5, with Apollo 11 selected (repeat the search if necessary), tap the Orbit icon and wait for the display to swing around. Next, use the Search command to find Earth. Our lovely half-illuminated planet will appear. For fun, reveal the time flow commands and tap the minutes — the number will become underlined. Finally, tap the far right and left arrows to flow time forward and backward, respectively. I doubt Neil and Buzz had time to enjoy looking at us, but it would have been a pretty sight indeed!

Going beyond

While most astronomers dismiss astrology, there's no question that people are curious about how the sky looked during life's milestones. Would your parents have seen a full moon, or bright Venus, on the way to the hospital on your birth date? Or perhaps you'd like to schedule a wedding under a spectacular sky. Just use the settings to enter the appropriate locations and dates.

In a future edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll show you how to re-create the discoveries of Uranus, Neptune, Ceres and Pluto in the centuries since Galileo by following their slow passage through the fixed stars. In the meantime, keep looking up!

Editor's note: Chris Vaughan is an astronomy public outreach and education specialist at AstroGeo, a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, and an operator of the historic 74-inch (1.88 meter) David Dunlap Observatory telescope. You can reach him via email, and follow him on Twitter @astrogeoguy, as well as on Facebook and Tumblr.

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.