Nearby Stars Come Out of Hiding

Astronomers have spotted 20 new star systems in our local solar neighborhood, adding to a rapidly growing list of known stellar residents in our galaxy.

The just-discovered stars reside within 33 light years of Earth and include the 23rd and 24th closest stars to the Sun. The closest is a three-star system called Alpha Centauri located 4.36 light years from Earth. Within the past six years, astronomers' catalogue of nearby stars has ballooned by 16 percent.

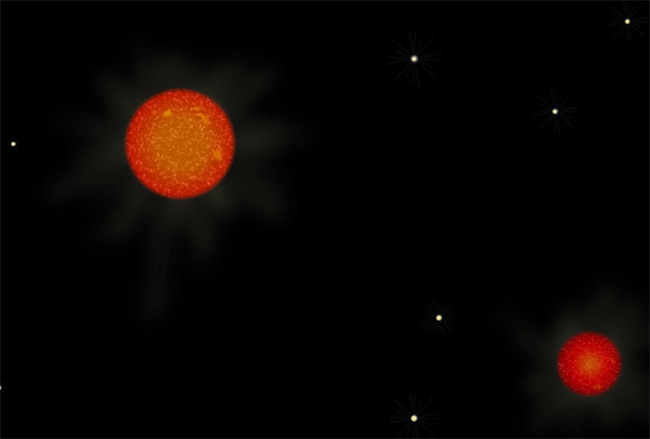

The 20 newly reported objects are all red dwarf stars, which now account for 69 percent of the Milky Way's residents. Finding these relatively dim stars has not been easy.

"Red dwarfs are among the faintest but most populous objects in the Milky Way," said team leader Todd Henry of Georgia State University. "Although you can't see a single one with the naked eye, there are swarms of them throughout the galaxy."

The results, detailed in the December issue of the Astronomical Journal, include a binary red dwarf setup called SCR 0630-7643 AB [image] located 28.7 light years from Earth. The two stars orbit each other every 50 years or so and are within 7.9 astronomical units (AU) of each other, a bit less than the distance between the Sun and Saturn (1 AU is the distance from Earth to the Sun).

The research team, called the Research Consortium on Nearby Stars (RECONS), has been peering at the night skies with small telescopes at the National Science Foundation's Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in the Chilean Andes since 1999.

"Our goal is to help complete the census of our local neighborhood and provide some statistical insights about the demographics of stars in our galaxy-their masses, their evolutionary states, and the frequency of multiple star systems," Henry said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The distances to these stars were measured using what is called a parallax technique, which takes advantage of the simple geometry of Earth's changing position in the cosmos as it orbits the Sun each year. From Earth, nearby stars appear to make tiny ellipses in the sky because the Earth does not jump from one side of its orbit to another, but slides smoothly around the Sun.

Bringing this down to Earth, the far points of our planet in its orbit would be the positions of your eyes on your face. And the size of the apparent motion of your finger depends on how close you hold it to your eyes-when nearer, it seems to jump more, relative to distant background objects.

With observations over several years, the astronomers could make parallax measurements with an accuracy of about one two-millionth the width of the full Moon.

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Video: When Stars Collide

- A Billion Stars Hiding in Milky Way

- Images: Spitzer's Infrared Views of the Cosmos