A Billion Stars Hiding in Milky Way

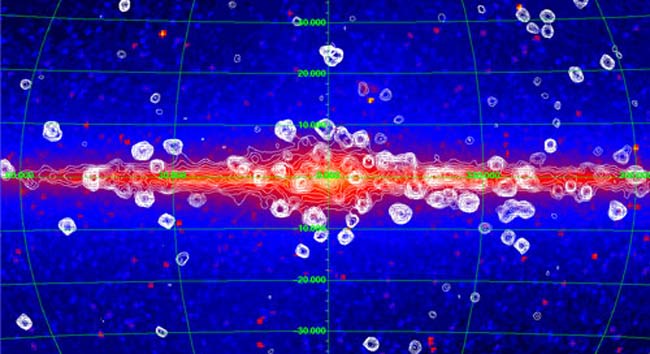

Astronomers have found that a diffuse X-ray glow in our galaxy is not generated by hot gas but rather it's radiating from old stars that have yet to be counted.

There could be roughly a billion stars we didn't know about in the Milky Way, they said Wednesday.

The discovery, if confirmed, "would have a profound impact on our understanding of the history of our galaxy, from star-formation and supernova rates to stellar evolution," according to a statement released by NASA.

X-rays are a form of light, like visible light be much more energetic.

Researchers have measured the X-ray background, as they call it, for years. It is more pervasive than the milky optical haze that gives our galaxy its name. Scientists have assumed some of the X-rays came from unseen stars but the leading theory held that most of it was created by hot gas, which would explain the diffuse nature of the glow.

A movie of known X-ray sources, mostly neutron stars and black holes, was unveiled last month by SPACE.com. The new study reveals the hidden sources from the same research effort.

The research, based on a decade of data from NASA's Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer, suggests the galaxy is "teeming with X-ray stars, most of them not very bright, and that scientists over the years had underestimated their numbers."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"From an airplane you can see a diffuse glow from a city at night," said lead researcher Mikhail Revnivtsev of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany. "To simply say cities produce light is not enough. Only when you get closer do you see individual sources that make up that glow-the house lights, street lamps and automobile headlights. In this respect, we have identified the individual sources of local X-ray light. What we found will surprise many scientists."

Scientists at the Russian Academy of Sciences and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center worked on the study, which will be detailed in a future issue of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Specifically, the glow comes from two main sources, the scientists say.

One source is a paired-star arrangement called a cataclysmic variable. These setups involve one regular star and a burned out shell of a star called a white dwarf. The dwarf pulls matter from the companion, and the gas heats up and releases X-rays.

The other source: active stellar coronas. These also involve a binary arrangement, in which one star stirs up the other's outer atmosphere, or corona, causing flares akin to those produced by our Sun.

The unseen stars have not all been counted in the new study, however.

"When they're close enough, we can look at them and see what they're like," explained Jean Swank, project scientist for the Rossi mission at Goddard. "And then you can see how many there are in a certain volume of the galaxy."

That data was then extrapolated to estimate how many unknown and hard-to-see stars lurk in the Milky Way, Swank said in a telephone interview.

The new accounting suggests there are about a million cataclysmic variables and about a billion of the active corona setups. To confirm the numbers, Swank said, will require the Chandra X-ray Observatory to make surveys of the central region of the galaxy that are 10 times more sensitive than what it's been tasked to do so far.

Astronomers estimate the Milky Way contains about 100 billion stars.

- White Dwarf Sends Ripples Through Red Spider Nebula

- Milky Way vs. Andromeda: Study Settles Which Is More Massive

- The Milky Way: A Tourist's Guide

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.