New class of exoplanet! Half-rock, half-water worlds could be abodes for life

The find could boost the search for alien life.

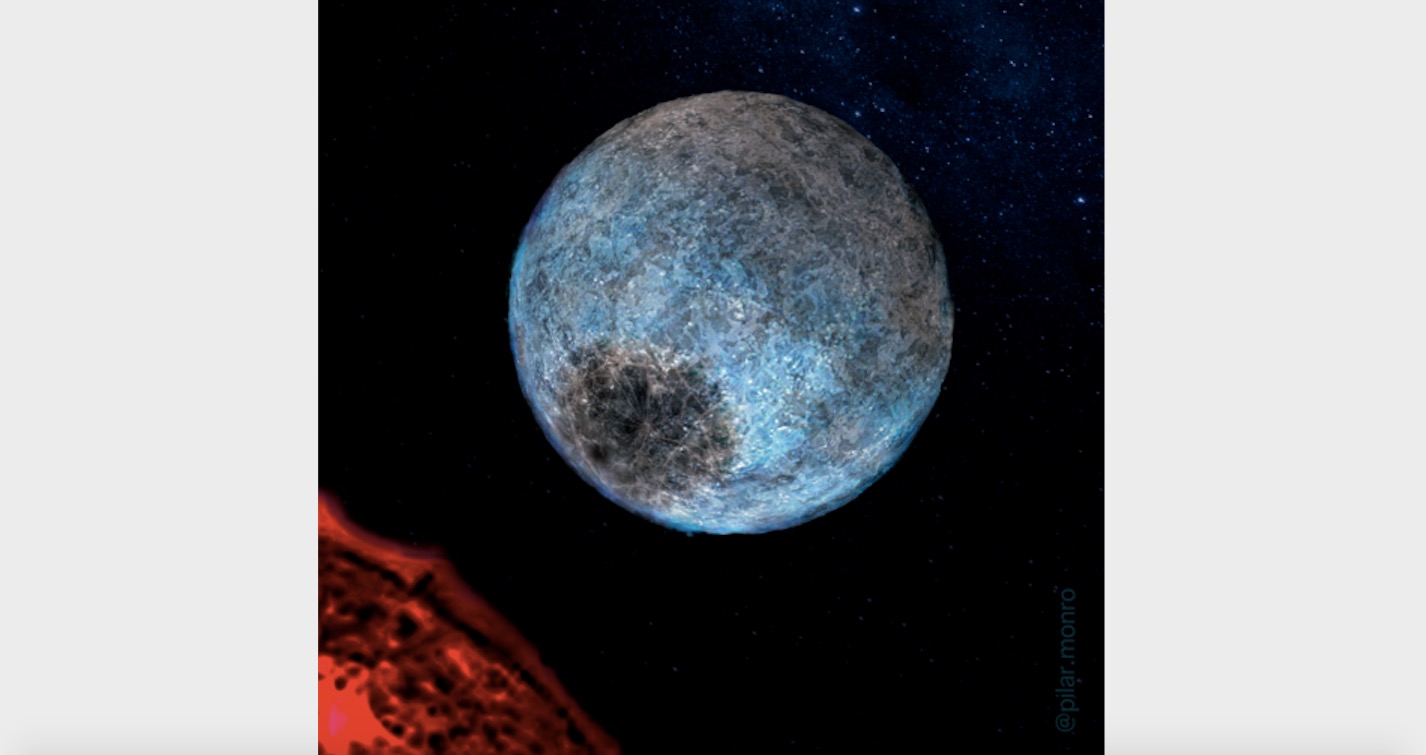

A new type of exoplanet — one made half of rock and half of water — has been discovered around the most common stars in the universe, which may have great consequences in the search for life in the cosmos, researchers say.

Red dwarfs are the most common type of star, making up more than 70% of the universe's stellar population. These stars are small and cold, typically about one-fifth as massive as the sun and up to 50 times dimmer.

The fact that red dwarfs are so very common has made scientists wonder if they might be the best chance for discovering planets that can possess life as we know it on Earth. For example, in 2020, astronomers that discovered Gliese 887, the brightest red dwarf in our sky at visible wavelengths of light, may host a planet within its habitable zone, where surface temperatures are suitable to host liquid water.

Related: 10 exoplanets that could host alien life

However, whether the worlds orbiting red dwarfs are potentially habitable remains unclear, in part because of the lack of understanding that researchers have about these worlds' composition. Previous research suggested that small exoplanets — ones less than four times Earth's diameter — orbiting sun-like stars are generally either rocky or gassy, possessing either a thin or thick atmosphere of hydrogen and helium.

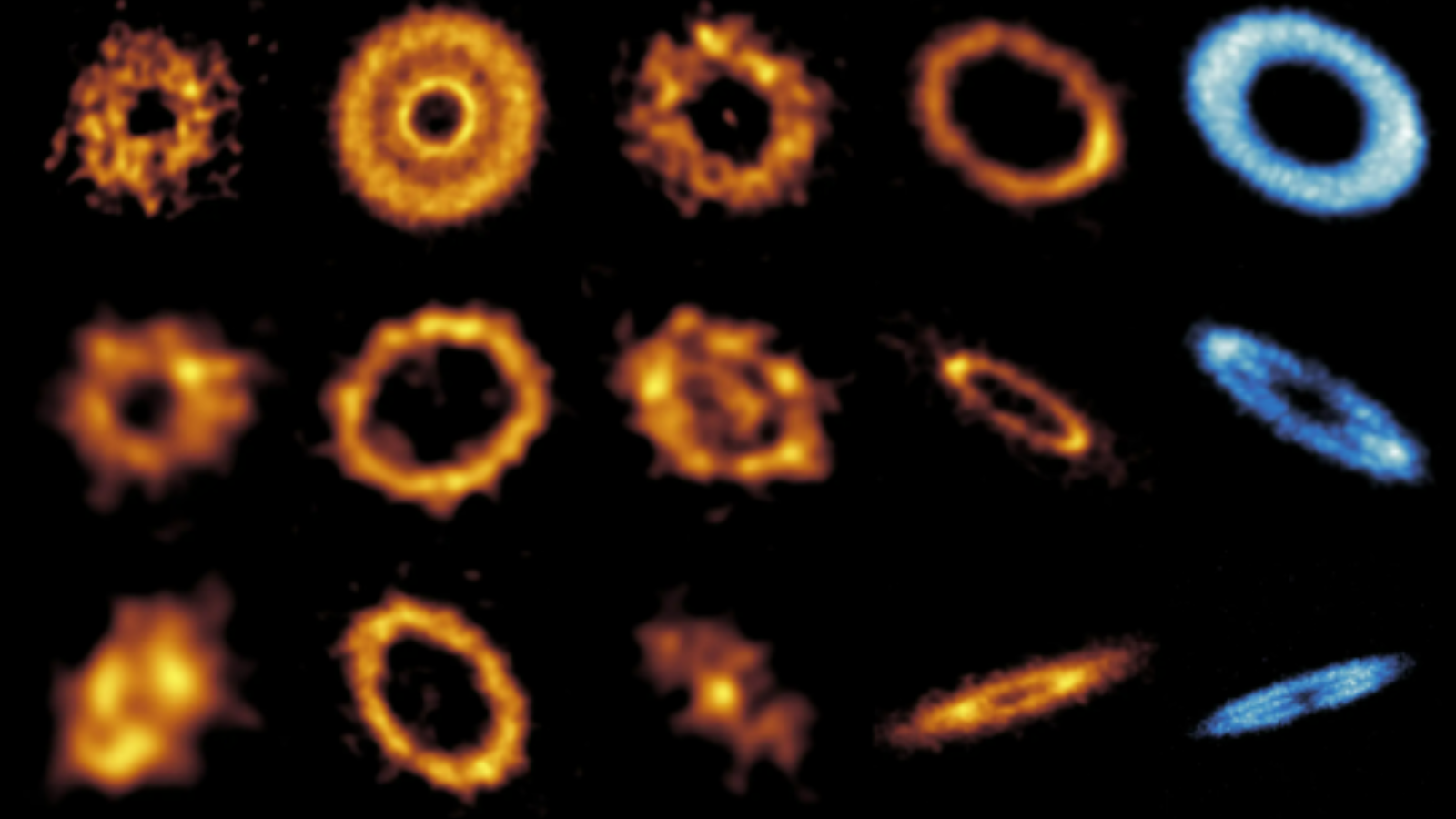

In the new study, astrophysicists sought to examine the compositions of exoplanets around red dwarfs. They focused on small worlds found around closer — and thus brighter and easier to inspect — red dwarfs observed by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

Stars are much brighter than their planets, so astronomers cannot see most exoplanets directly. Instead, scientists usually detect exoplanets via the effects these worlds have on their stars, such as the shadow created when a planet crosses in front of its star, or the tiny gravitational tug on a star's motion caused by an orbiting planet.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By catching the shadow created when a planet crosses in front of its star, scientists can find the diameter of the planet. By measuring the small gravitational pull that a planet exerts on a star, researchers can find its mass.

In the new study, astrophysicists ultimately analyzed 34 exoplanets about which they had precise data on diameter and mass. These details helped the researchers estimate the densities of these worlds and deduce their likely compositions.

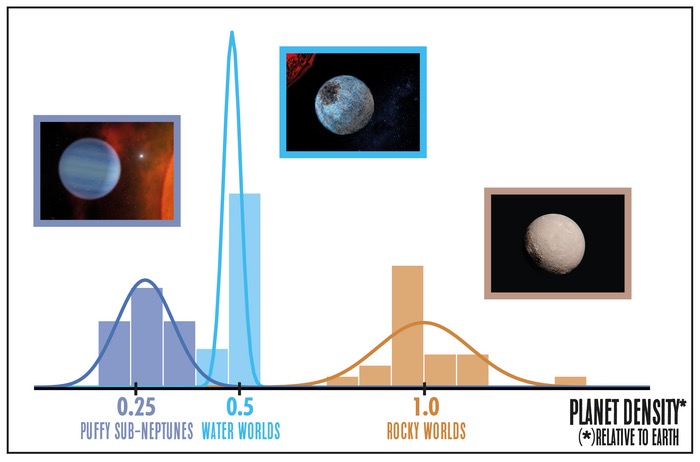

"We can divide these worlds into three families," study co-author Rafael Luque, an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago, told Space.com in an interview. In addition to 21 rocky planets and seven gassy planets, they found six examples of a new type of exoplanet, watery, which is made of about half-rock and half-water, either in liquid or ice form.

"It was a surprise to see evidence for so many water worlds orbiting the most common type of star in the galaxy," Luque said in a statement. "It has enormous consequences for the search for habitable planets."

The scientists' planetary formation models suggest the small planets they detected likely evolved in three different ways. The rocky planets may have formed from relatively dry material near their stars.

Related: 7 ways to discover alien planets

The small rocky planets have a density "nearly identical to Earth's," study co-author Enric Pallé, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands, told Space.com. "That means their compositions must be very, very similar."

In contrast, the watery planets likely arose from icy material and were born far away from their stars, past the "ice line" where surface temperatures are freezing. They later migrated closer in to where the astronomers detected them.

The gassy planets are also water-rich and may have formed in a similar manner to the watery planets. However, they likely initially possessed more mass and could therefore gather a hydrogen and helium atmosphere around themselves before venturing inward.

Although the rocky planets are relatively poor in water and the watery planets rich in it, that might not mean the former are arid and the latter are covered in oceans, the researchers said.

"Earth only has 0.02% of its mass in the form of water, which makes it from the astrophysics point of view a dry world, even though three-fourths of the surface is covered in water," Pallé said. In contrast, although the watery planets the researchers discovered are half-water, "that doesn't necessarily mean they have massive oceans on their surface," Pallé said. "The water seems mixed with the rock."

Future research can see if these three kinds of worlds are also found around larger stars, Luque said. "A new generation of instruments in ground-based telescopes, especially in the U.S. and Europe, are going to enable us to make these measurements," Luque said in the interview.

Another direction to follow up on is investigating the composition and properties of these watery worlds. "With the James Webb Space Telescope, we can analyze their atmospheres, if they have any, and see how they store water," Luque said in the interview. "This will tell us a lot about their formation and evolution and internal structure."

The scientists detailed their findings online Thursday (Sept. 8) in the journal Science.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us