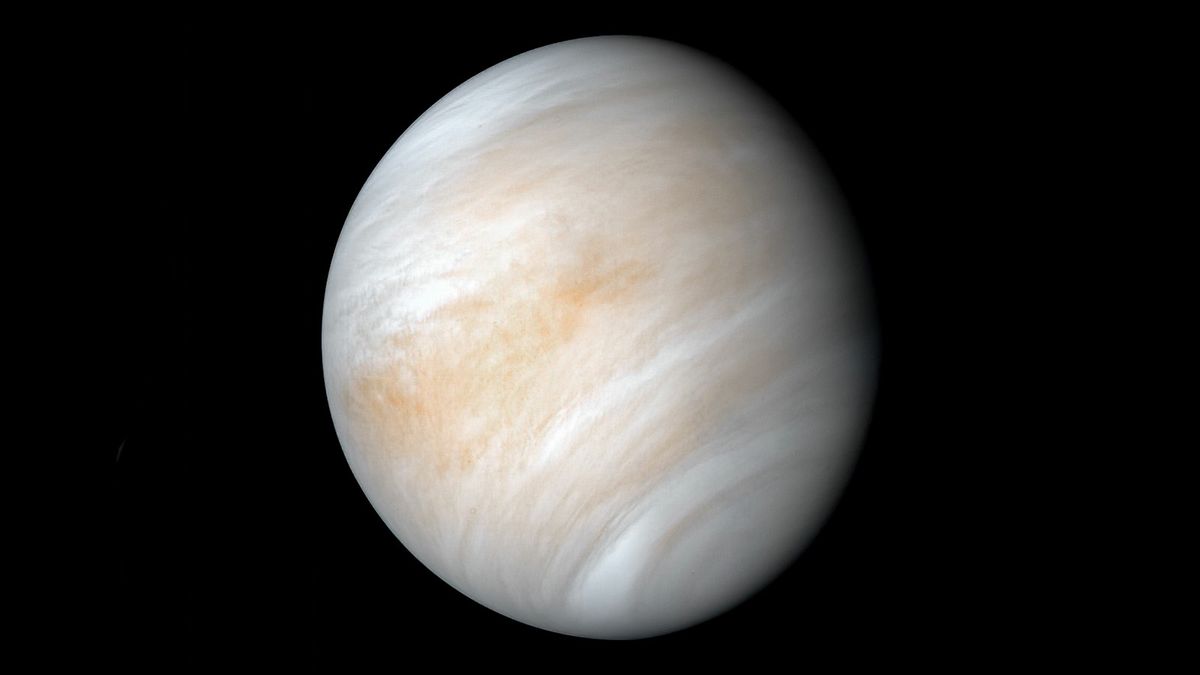

Why Venus is back in the exploration limelight

Venus is getting some long-overdue love.

On Wednesday (June 2), NASA announced that it will launch two missions to Earth's hellishly hot sister planet by 2030 — an orbiter called VERITAS and an atmospheric probe known as DAVINCI+.

The duo will break a long Venus drought for the space agency, which hasn't launched a dedicated mission to the second rock from the sun since the Magellan radar-mapping orbiter in 1989.

Related: Photos of Venus, the mysterious planet next door

Other organizations are putting Venus in the crosshairs as well. For example, the space agencies of Europe, India and Russia are all developing Venus mission concepts for potential launch in the next decade or so. And the California-based company Rocket Lab aims to send a life-hunting mission to the planet in 2023.

Indeed, we may well be witnessing the start of a bona fide Venus exploration campaign.

"My sense is that people are going to be surprised by how interesting [Venus] is," said planetary scientist David Grinspoon, a member of the DAVINCI+ team and a longtime advocate for more in-depth study of Venus.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"And if that is the case, then the results of the early missions will also feed a desire for more missions, because it's a very complex and vibrant and interesting place," Grinspoon, who's based at the Planetary Science Institute, told Space.com.

A focus of early exploration

Venus has been in the limelight before. The Soviet Union targeted the planet frequently from the 1960s through the mid-1980s with its Venera and Vega programs, notching a variety of exploration milestones along the way (despite a number of launch failures).

In October 1967, for instance, Venera 4 became the first probe ever to beam data home from the atmosphere of another world, finding that Venus' surface is incredibly hot and its air surprisingly thick. Three years later, Venera 7 performed the first successful soft landing on a planet other than Earth.

In 1982, the Venera 13 lander recorded the first-ever audio on the surface of another world (an accomplishment recently mirrored on Mars by NASA's Perseverance rover). And in the mid-1980s, the Vega 1 and Vega 2 missions successfully deployed balloon probes in the thick Venusian atmosphere, another off-Earth first.

The United States mounted some Venus missions during this stretch as well, though not nearly as many as its Cold War rival did. NASA's Mariner 2, Mariner 5 and Mariner 10 spacecraft performed flybys of the planet in 1962, 1967 and 1974, respectively. And in 1978, the space agency launched both the Pioneer Venus Orbiter and the Pioneer Venus Multiprobe. The multiprobe sent four instrument-laden entry craft into Venus' atmosphere in December of that year, and the orbiter studied Venus from above until 1992.

Then there was Magellan, which was the first interplanetary mission ever to launch from the space shuttle. The probe mapped Venus in detail using synthetic-aperture radar until October 1994, when its handlers sent Magellan down to its death in the Venusian atmosphere.

The list gets pretty thin after that. Europe's Venus Express orbiter studied the planet, with a focus on its atmosphere, from 2006 to 2014. And Japan's Akatsuki orbiter has been doing its own atmospheric investigations since arriving at Venus, after some tenacious troubleshooting, in December 2015.

Related: Here's every successful Venus mission humanity has ever launched

A return to Venus

Venus faded as an exploration target for several reasons. The decline of the Soviet Union and its eventual collapse in the early 1990s had a chilling effect, for example; Vega 2 remains the last successful fully homegrown interplanetary mission launched by the Soviet Union or its successor state, Russia. (Russia's federal space agency, Roscosmos, and the European Space Agency are working together on the ExoMars project, which launched an orbiter to the Red Planet in 2016 and plans to send a life-hunting rover there in 2022.)

In addition, throughout the 1990s and beyond, NASA increasingly focused its robotic exploration efforts on Mars, whose surface bears unmistakable signs of past water activity and is much more welcoming to landers and rovers. Even the most successful Venus landers have survived for mere hours on the planet's surface, which is hot enough to melt lead.

"It's sort of understandable why Venus wasn't picked for a while [by NASA], because Venus is a hard place to explore," Grinspoon said. "You're never going to get the same data return, in terms of megabits of data, from a Venus mission as you would from a Mars mission."

But the pendulum could swing only so far from Venus before heading back the planet's way. For starters, as scientists have gathered more and more detailed knowledge about other solar system bodies such as Mars, Mercury and Pluto, the gaps in our understanding of Venus, which is similar to Earth in size and mass, became increasingly obvious.

Venus has "been so neglected that now the mysteries — it's almost an embarrassment, or certainly an impediment, to our fully understanding our solar system," Grinspoon said.

In addition, scientists think that Venus was once very different — a balmy, temperate world with oceans, rivers and streams. Recent research even suggests that the planet's surface was habitable for Earth-like life for several billion years, until a runaway greenhouse effect took hold around 700 million years ago.

And parts of Venus may still be habitable today. About 30 miles (50 kilometers) above the planet's scorching surface, temperatures and pressures are quite Earth-like, so it's possible that microbes even now reside in the Venusian skies, wafting about with the sulfuric-acid clouds.

Intriguingly, those skies feature mysterious dark patches where ultraviolet radiation is absorbed — perhaps by a sulfur-based pigment that microbes produce to protect against sunburn, some scientists have speculated. And one team of researchers recently announced that they'd spotted the signature of phosphine, a possible biosignature gas, around that 30-mile altitude. The apparent phosphine find has not been confirmed by other teams, however, and remains the topic of considerable discussion and debate.

Related: 6 most likely places for alien life in the solar system

So Venus has become a more attractive astrobiological target in recent years, just as the search for alien life has increasingly moved from the scientific fringes into the mainstream.

That transition has been helped along by the ongoing exoplanet revolution, which has revealed that the universe is teeming with potentially habitable worlds. And exoplanet scientists are keen to learn more about Venus, adding to the planet's accruing allure.

"There's a lot of interest from the exoplanet community in exploring Venus, because it's obvious to anybody that sort of thinks about solar systems, planetary systems, systematically that understanding the Venus-Earth difference is really key to understanding how planets evolve in general, and how habitable conditions evolve," Grinspoon said.

There's also a more practical reason to learn exactly how Venus became a scorching hellscape. Humanity is pushing Earth in that dangerous direction via deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels, after all, and Venus can be a natural laboratory in addition to a cautionary tale.

"There's a lot that we still need to learn about climate and how it changes on Earth-like planets, and Venus being sort of an extreme case can really push our models to the limit," Grinspoon said. "There's a value to the comparative study of similar planets that makes you wiser about how your own operates and changes, and I think that Venus is just too valuable in that regard for us to ignore any longer."

The coming missions

VERITAS and DAVINCI+ were selected by NASA's Discovery program, which develops relatively low-cost exploration projects. The price tag of each mission is capped at around $500 million, and each is expected to launch between 2028 and 2030.

VERITAS (short for "Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy") will map Venus' surface in detail from orbit using radar and monitor infrared surface emissions, which will reveal how rock type varies from place to place. Such observations will shed light on Venus' geologic history and climate evolution and help researchers determine if the planet hosts active plate tectonics and volcanism today, NASA officials said.

DAVINCI+ ("Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry and Imaging") will send a "descent sphere" through Venus' thick air. The probe will measure atmospheric composition as it falls, returning data that will teach scientists more about how the planet went hothouse. The DAVINCI+ team also plans to look for phosphine, Grinspoon said.

"It is astounding how little we know about Venus, but the combined results of these missions will tell us about the planet from the clouds in its sky through the volcanoes on its surface all the way down to its very core," NASA Discovery Program scientist Tom Wagner said in a statement on Wednesday. "It will be as if we have rediscovered the planet."

The two NASA missions will follow on the heels of a privately funded Venus effort, if all goes according to plan: Rocket Lab aims to launch a Venus mission in 2023 using its Electron rocket and Photon satellite bus. Details are still being worked out, but the goal is to use an atmospheric probe to hunt for signs of life in the balmy patch of Venus' skies.

"We're going to learn a lot on the way there, and we're going to have a crack at seeing if we can discover what's in that atmospheric zone," Rocket Lab founder and CEO Peter Beck said last summer when announcing the project. "And who knows? You may hit the jackpot."

That initial mission could even kick off an extended Rocket Lab Venus campaign, Beck has said.

Related: The 10 weirdest facts about Venus

Those private missions could in turn be part of a larger, global exploration effort, for there are other Venus plans afoot as well. For example, a Venus orbiter concept called EnVision is one of three medium-class missions that the European Space Agency is considering for launch in 2032. The winner is expected to be announced this month, perhaps as soon as this week.

The Indian Space Research Organisation is developing a potential Venus mission of its own, called Shukrayaan-1, which would launch in 2024 or 2026. That project would include an orbiter and an atmospheric balloon probe.

And Russia aims to go back to Venus at long last, with an ambitious mission called Venera-D that would feature an orbiter, a lander and atmospheric balloons. Venera-D will launch in 2029, if all goes according to plan.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.