The phosphine discovered in Venus' clouds may be a big deal. Here's what you need to know.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

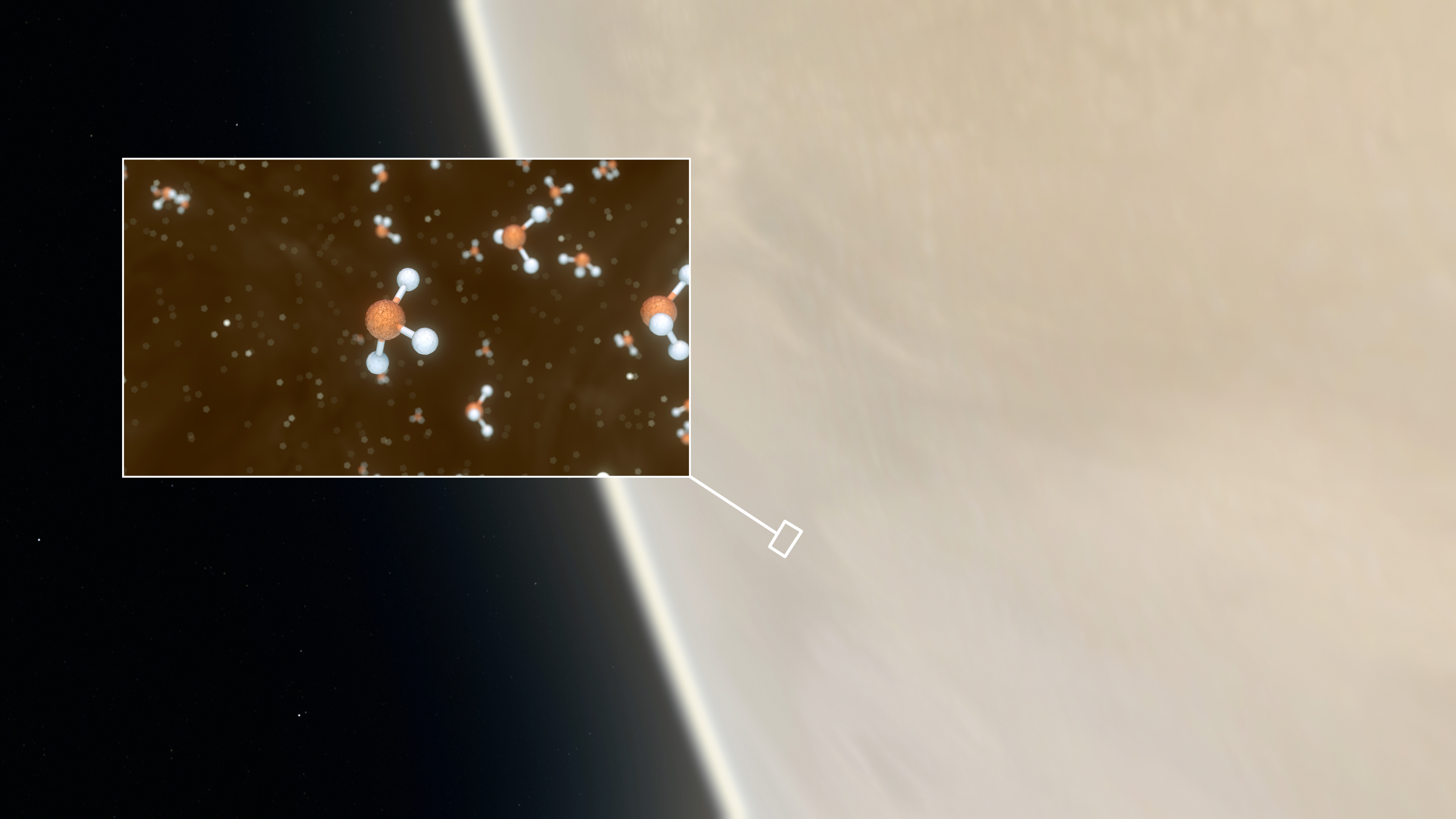

A chemical you've likely never heard of has burst into the news thanks to scientists' announcement that they have detected phosphine, which they say may be a sign of life, in the clouds of Venus.

Phosphine is a chemical compound made up of one atom of phosphorus and three atoms of hydrogen, and scientists have also spotted it on Earth, Jupiter and Saturn. On the gas giants, it's quite prevalent in the atmospheres, both of which are rich in hydrogen. On Earth, where the atmosphere leans more toward oxygen compounds, it's much shorter-lived, and the same ought to be true on Venus.

"It's so obscure," Sara Seager, an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and co-author on the new research, said during a news conference held virtually today (Sept. 14). "No one cares about [phosphine] except for a few very niche people."

Article continues belowRelated: Strange chemical in Venus clouds defies explanation. A sign of life?

That's less true for Jupiter and Saturn — scientists have been studying phosphine in those clouds for decades now. The new research may not be the first sighting of the compound at Venus, either. The Soviet Union's Vega probes detected a phosphorus-containing chemical in the local clouds in the 1980s, although their instruments weren't sophisticated enough to make a precise identification.

On Earth, the compound has been intriguing, but it is difficult to study in laboratories, so scientists have tended to focus their efforts elsewhere. Humans produce it industrially, although perhaps not for the most uplifting reasons.

"Most of us are familiar with phosphine as rat poison," Matthew Pasek, an astrobiologist and geochemist at the University of South Florida who has worked on phosphorus cycling issues but was not involved in the new research, told Space.com. "It's something that we make to kill things — microbes aren't really killed by it, but larger organisms are."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists have also found phosphine near communities of specific microorganisms, although they haven't closely investigated how it comes about. Although the researchers on the new finding say that on Earth, the compound is produced by microbes, Tetyana Milojevic, a biochemist at the University of Vienna not involved in the new research, told Space.com that we don't have firm evidence of that. Instead, it may simply be a product of microbial matter decaying chemically.

"The way we understand phosphine nowadays, this is the sign of biological degradation of biomass, decay of biological matter," Milojevic said. "This happens not to biological activity of those microorganisms, not due to their enzymatic action, but rather affected by physical chemical constraints." It also seems to form when iron-rich substances with small amounts of phosphorus meet acidic environments, she said — a likely scenario in Venus' clouds.

Fortunately, those gaps in understanding phosphine itself won't take a journey to Venus to fill. Conducting those missing laboratory experiments will tell scientists whether and how microbes produce phosphine here on Earth, bringing them a step closer to what it might mean on Venus.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.