Scientists just found the biggest neutron star (or smallest black hole) yet in a strange cosmic collision

Whatever it is, scientists are excited.

Astrophysicists have spotted the strangest gravitational-wave signal yet, an observation that could force scientists to rewrite what they know about the cosmos.

Gravitational waves form when massive objects distort spacetime surrounding them and send ripples out across the universe. Scientists caught the first-ever detection of such waves, formed by two colliding black holes, in 2015.

Since then, gravitational wave detections have only gotten stranger — and scientists have only gotten more excited. Now, a group of researchers has announced the first detection of a gravitational-wave signal created by a collision involving an object larger than the largest known neutron star but smaller than the smallest known black hole. Although the detection is too complicated for scientists to ever hope to pin down precisely what happened, the signal raises hopes for more strange observations to come. This detection could even herald a new understanding of how massive stellar explosions called supernovas happen.

"It's a fantastic event, it will really change how we understand the formation of black holes and neutron stars," Christopher Berry, a gravitational wave astronomer at Northwestern University and the University of Glasgow and co-author on the new research, told Space.com. "It will remain a mystery until we can get more observations, but that doesn't mean it's not informative."

Related: The search for gravitational waves in images

"We're very confident in the results, this is a really beautiful signal," he said. "It's a wonderful, clean chirp if you look at the data. I couldn't believe it the first time I saw it, it's stunning."

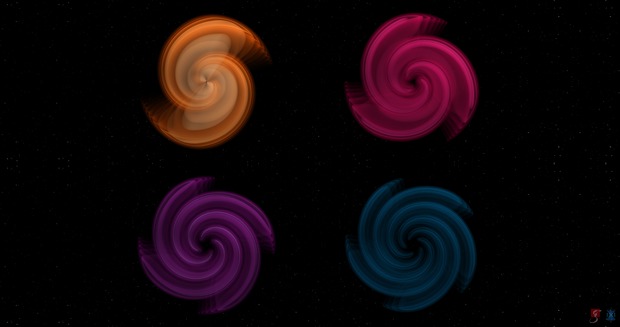

Scientists caught the gravitational wave, or the "chirp," on Aug. 14, 2019 and were further intrigued when initial analysis suggested that the collision could have merged a black hole and a neutron star. The collision of those two objects is a type of gravitational wave event that scientists have eagerly been awaiting, since so far they have only seen mergers of matched pairs.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

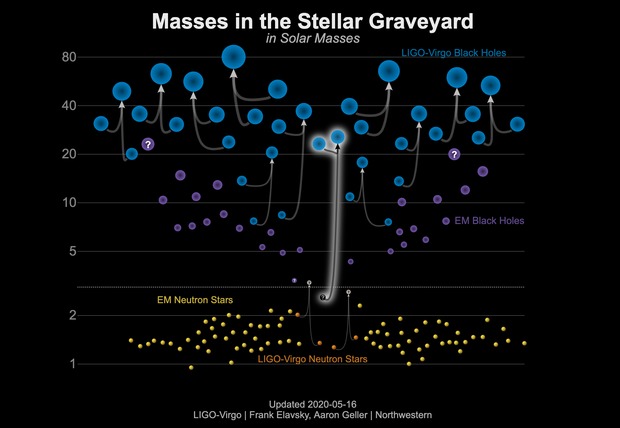

But as the astrophysicists ran more analyses on the data, they realized they were looking at something even stranger. According to scientists' analysis of the merger event, one of the colliding objects was about 23 times the mass of our sun — that's a black hole — and the other about 2.6 times the mass of our sun — that's a … well, that's something.

Mass-gap mystery

This size falls into what scientists call the mass gap: an object significantly smaller than any black hole studied to date (about 5 times the mass of the sun), but also probably larger than any known neutron star (about 2.5 times the mass of the sun).

"Mergers of a mixed nature — black holes and neutron stars — have been predicted for decades, but this compact object in the mass gap is a complete surprise," co-author Vicky Kalogera, an astrophysicist at Northwestern University, said in a statement. "Even though we can't classify the object with conviction, we have seen either the heaviest known neutron star or the lightest known black hole. Either way, it breaks a record."

Under other circumstances, scientists may have been able to determine what the object actually was before the collision that created the observable chirp. But fate didn't cooperate here. Scientists didn't spot any light signal that a neutron star could have produced — but that doesn't rule out that it could have been a neutron star.

And unlike the generally well-matched collisions scientists have studied to date, this pair is hugely uneven, with the larger object containing about nine times the mass of the smaller one, making it even more difficult for scientists to see details of the event in the gravitational wave chirp. "I think of Pac-Man eating a little dot," Kalogera said in the statement. "When the masses are highly asymmetric, the smaller compact object can be eaten by the black hole in one bite."

The event was also difficult to study because it was quite far away. The collision appears to have occurred about 800 million light-years away from Earth — for context, that's about six times more distant than the binary neutron star merger detected in August 2017 by its accompanying flash of light.

Because of these challenges, to really crack the mystery of the cosmic mass gap, scientists will need to observe more of these borderline objects in more collisions, preferably collisions that aren't quite so complicated to analyze. "A more equal-mass binary would be great, one closer even better," Berry said.

And pinning down the fuzzy realm between neutron star and black hole isn't important just for precision's sake, Berry said: it will change our understanding of the universe around us.

For one thing, it will tell scientists about how neutron stars — which Berry called "the ultimate particle colliders" — work. "Neutron star matter is very difficult to model," he said. "It's nothing we can simulate here on Earth, the conditions are too extreme." But the properties of that matter will determine the maximum size of a neutron star, the point at which a large neutron star becomes too large and collapses, the boundary that observations like this new research will help pin down.

And understanding the mass gap (or lack thereof) would ripple through astrophysics far beyond these observations, Berry said. For decades now, astrophysics models have assumed that there is indeed a gap between the largest neutron stars and the smallest black holes. If that gap turns out to be significantly smaller than previously assumed, or nonexistent, those models will need to be tweaked. Those tweaked models could change our understanding of the universe more broadly than the mass gap definition itself, Berry said.

However the mass gap mystery unfolds, this new signal points to the rich future of gravitational wave observations, Berry said.

"This is testament to the fact that we are only just starting to explore the universe with gravitational waves," he said. "We don't know what's out there. We've seen some of the more common sources now, we know what the typical type of gravitational waves are. But the full complexity, what the rare beasts in the jungle are, we're still trying to find out."

The research is described in a paper published today (June 23) in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

- In images: The amazing discovery of a neutron-star crash, gravitational waves & more

- The universe remembers gravitational waves — and we can find them

- With new gravitational-wave detectors, more cosmic mysteries will be solved

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.