Surprise! Pluto may have had an underground ocean from the very beginning

Pluto may be a more habitable world than scientists had thought.

Though Pluto is now famously frigid, it may have started off as a hot world that formed rapidly and violently, a new study finds.

This result suggests Pluto may have possessed an underground ocean since early on in its life, potentially improving its chances of hosting life, researchers said.

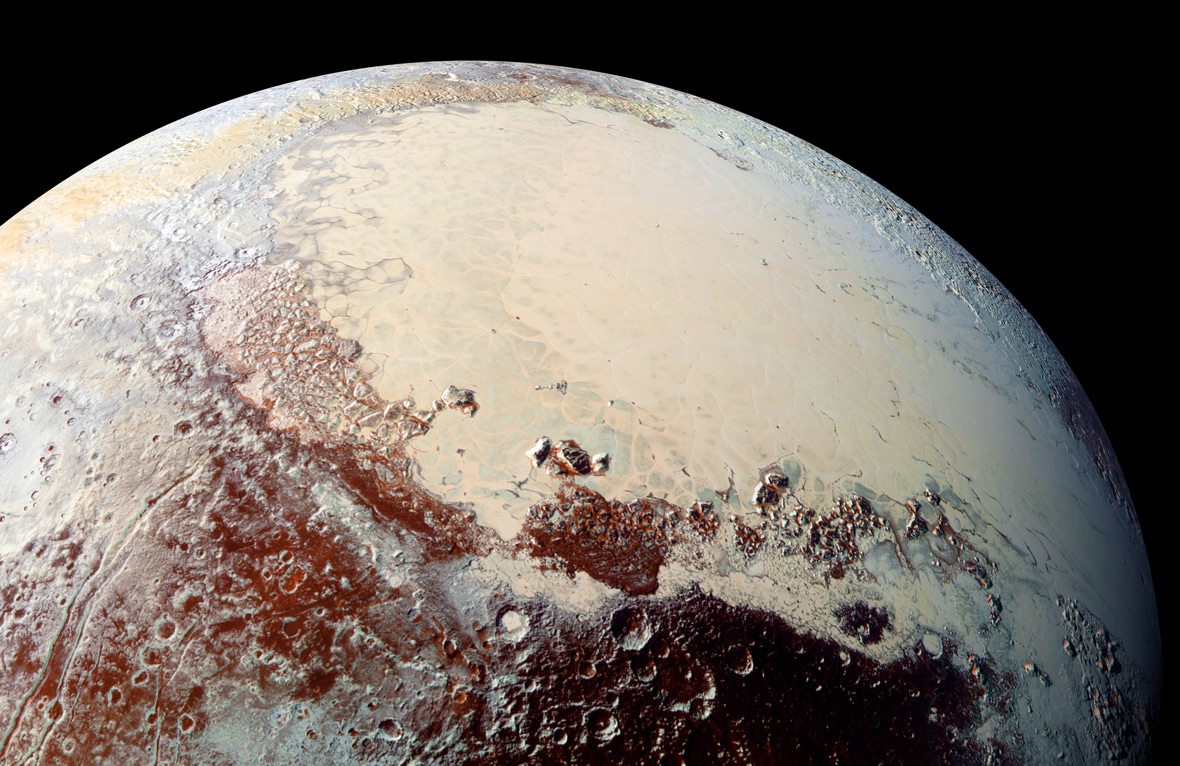

Previous work assumed Pluto originated from cold and icy rock clumping together in the distant Kuiper Belt, the ring of objects beyond Neptune's orbit. Although there is evidence that Pluto currently possesses a liquid ocean beneath its thick frozen shell, researchers have suggested this subsurface ocean developed long after Pluto formed, after ice melted due to heat from radioactive elements in Pluto's core.

Related: Photos of Pluto and its moons

Now scientists argue that instead of a cold formation, Pluto had a hot start, one full of explosive force.

"When we look at Pluto today, we see a very cold frozen world, with a surface temperature of about 45 Kelvin [minus 380 degrees Fahrenheit, and minus 228 degrees Celsius]," study lead author Carver Bierson, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, told Space.com. "I find it amazing that by looking at the geology recorded in that surface, we can infer Pluto had a rapid and violent formation that warmed the interior enough to form a subsurface water ocean."

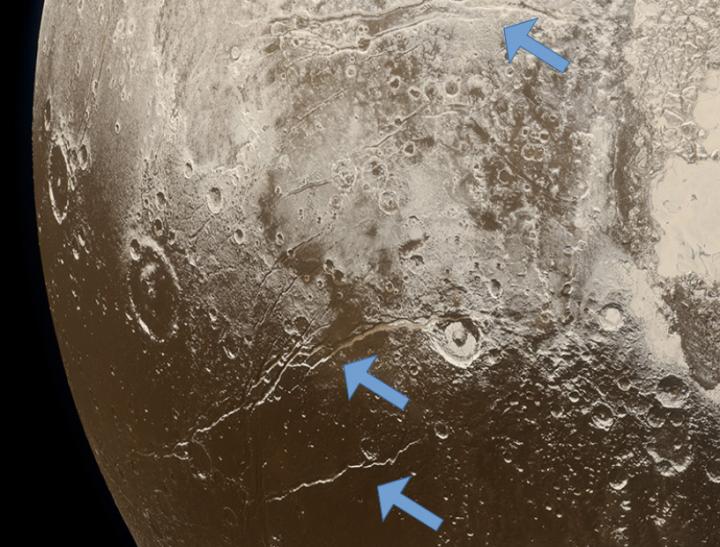

The researchers analyzed so-called "extensional features" on Pluto's surface. Water expands as it freezes, so as Pluto's interior cooled, Pluto's surface stretched, generating recognizable structures.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists compared geological observations of Pluto captured by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, which flew by the dwarf planet in 2015, with various models of Pluto's origin and evolution. If Pluto had a cold start, its frozen shell would have experienced compression early in the world's history as heat from radioactive elements melted ice, and then extension later on after these radioactive elements broke down and Pluto cooled. However, they found the most ancient portions of Pluto's surface imaged at high resolution do not show any clear signs of compression.

If Pluto had a rapid, violent formation, the heat from the colliding rocks from which Pluto coalesced would have faded relatively quickly, leading the icy shell to grow rapidly, generating extensional features early in Pluto's history. This freezing would pause as heat from radioactivity became a major factor, and resume as radioactive elements broke down, slowly creating extensional structures over time.

Extensional features the researchers saw on Pluto's icy surface — for instance, cracks in its shell, and an enigmatic system of ridges and troughs — suggest Pluto had a hot start.

"I think the most exciting implication is that subsurface oceans may have been common among the large Kuiper Belt objects when they formed," Bierson said.

These findings suggest that Pluto and other large dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt, such as Eris, Makemake and Haumea, may have possessed subsurface oceans ever since they formed. This may have influenced the potential habitability of these distant icy worlds, the researchers said.

"At this point, we don't know the ingredients or recipe needed for life to emerge on any world," Bierson said. Still, "we think liquid water is an important ingredient, and this work suggests Pluto has had that for a long time."

Bierson did caution that New Horizons could only take high-resolution images of about half of Pluto's northern hemisphere.

"Maybe by chance we missed some ancient terrain that recorded large-scale compression," he said. "You can imagine that if you only looked at the geology of one-quarter of Earth's surface, you could learn a lot, but you would also be missing some context. For now, we can only work with what we have. It would take another spacecraft to go back and image the rest of the surface to really find out what we missed."

The scientists detailed their findings online June 22 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

- Pluto flyby anniversary: The most amazing photos from NASA's New Horizons

- NASA eyes a possible return to Pluto, with a longer stay

- New Horizons probe's July 14 Pluto flyby: Complete coverage

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us