NASA's new astronauts are excited for April's total eclipse: 'I'm going to be that little kid all over again' (exclusive)

They shared their research ahead of the next solar eclipse that crosses the United States on April 8.

New NASA astronaut Andre Douglas used to study the sun's behavior for a living.

This puts Douglas, who passed basic NASA astronaut training on March 5, in the perfect position to talk about the total solar eclipse 2024 that will sweep across the United States on April 8.

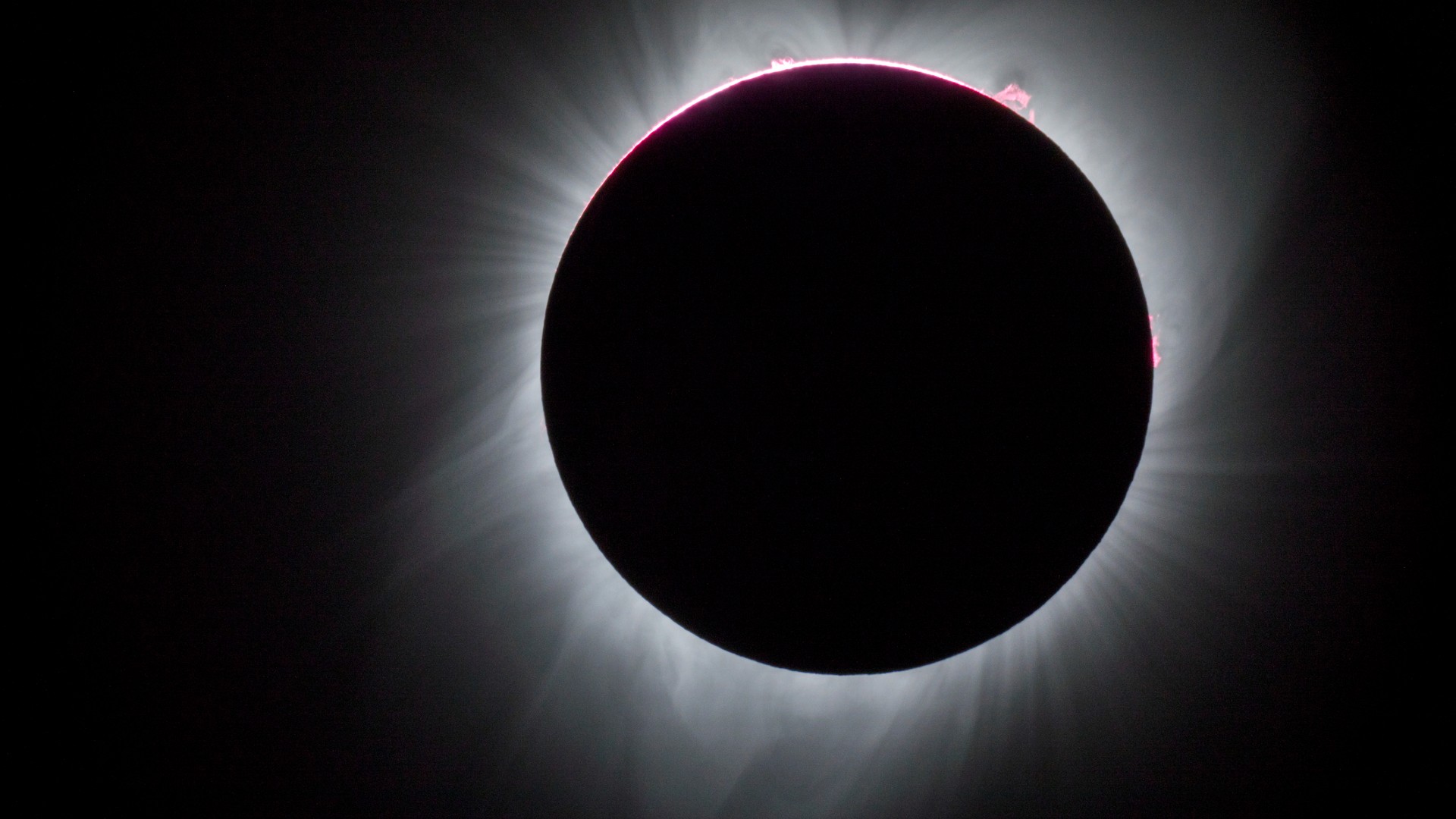

The moon will pass completely in front of the sun from the perspective of a small part of Earth along the path of totality, briefly creating a spectacular view, and Douglas is among a group of excited NASA astronauts celebrating the event. Douglas once participated in a mission proposal focused on sun science, which he shared with Space.com hours after he graduated from basic training.

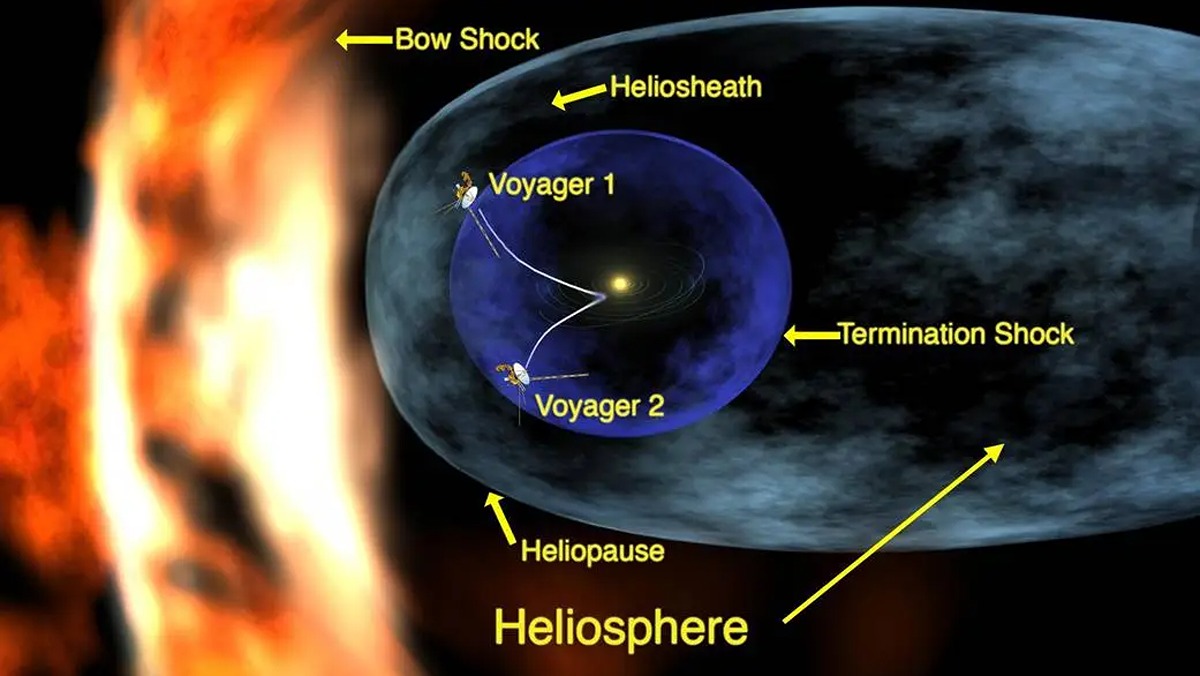

"We were trying to understand solar behavior, because our sun operates in 11-year-long cycles, and we were trying to understand the heliosphere," Douglas recalled. The heliosphere is the bubble in the solar system where the solar wind, or the constant stream of particles from our sun, exerts its influence: Auroras or the northern lights are one of the most popular examples of that.

Related: Total solar eclipse 2024: How and where to watch online for free

Douglas was previously an engineer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Baltimore, working on many missions. For the sun, he was on a team proposing a spacecraft rideshare mission called SIHLA, or Spatial/Spectral Imaging of Heliospheric Lyman Alpha.

SIHLA was one of two semi-finalists funded in 2019 to fly on a NASA mission slated to study interstellar space, and to map out the heliosphere. NASA's Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) mission will launch no earlier than 2025. (SIHLA was not selected for launch as an instrument to study Earth's atmosphere was picked instead, but SIHLA's work may be useful for future mission proposals.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While Douglas' work won't fly on IMAP, he did write some of the software for another spectacular NASA venture called DART or Double Asteroid Redirection Test, which successfully slammed into an asteroid moonlet in 2022. Douglas was a fault management engineer who wrote programming scripts ready to put DART's computer in "safe mode" if anything went wrong.

"These projects were pretty cool," Douglas said of his time at APL, including his solar science work. And he's not the only new NASA astronaut who used to study sun science frequently.

Related: NASA enlists citizen scientists to help solve solar mysteries during the total solar eclipse 2024

Christopher Williams, an astrophysicist and medical physicist before he joined NASA, said he's excited about the solar eclipse because it will give us unique views of the sun's outer atmosphere.

Williams knows in detail what to expect, as he once regularly studied stars: His work at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory examined supernovas, or star explosions, using a world-famous set of radio telescopes known as the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array. (The antennas are perched in the New Mexico desert and in Hollywood, once helped with alien communications for the 1997 movie "Contact" starring Jodie Foster.)

"I did radio astronomy research, looking at supernovas, and in particular, the radio emission from supernovas — which tells us about the history of the star that exploded," Williams explained. The supernova shockwaves that hit the solar wind give clues to stellar evolution through "looking how the light fades in radio [wavelengths]," he added, as this process produces unique signatures of light.

Using the Very Large Array to study these supernovas "was an awesome experience" that forged the long path that eventually brought Williams to NASA, he explained. His love of radio astronomy next allowed him to join the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he shifted his focus to cosmology or the universe's history.

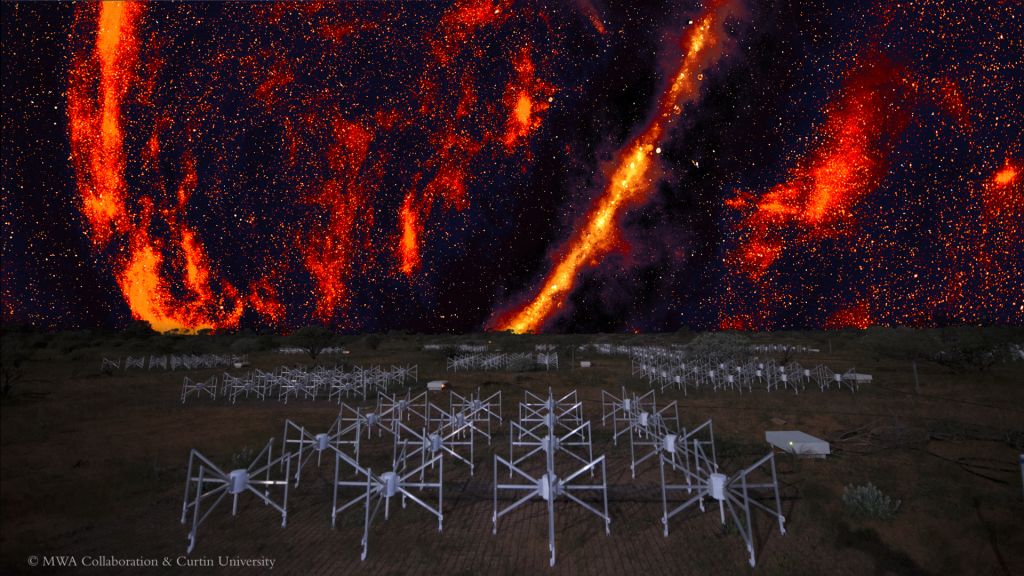

While with MIT, Williams worked far out in the desert of Australia. He was helping to build the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA), which uses more than 4,000 individual antennas spreading their view across a wide swath of sky. It's a great tool for both large-scale mapping of the cosmos, and catching brief events like supernovas.

"We were trying to get a get a picture of the so-called 'Dark Ages' of the universe, or the very early universe [about] 100,000 years after the Big Bang," Williams said of his research. The MWA investigation he worked on was looking at how hydrogen formed in that era; his team planned to investigate neutral hydrogen to in turn learn more about how the first stars and galaxies were formed.

Related: When did the 'dark ages of the universe' end? This rare molecule holds the answer

The first 380,000 years after the Big Bang saw matter and energy fused as superheated gas (or plasma) that constantly expanded along with the universe's size. There were too many collisions of subatomic particles in this era for electrons to form stable atoms. But after the universe was large enough and cool enough, electrons could be formed from subatomic particles.

That cooling time was when neutral hydrogen atoms were formed, although the atoms were ionized quickly after enough stars were born. The ultraviolet light photons from these young stars, no longer absorbed by the hydrogen, then traveled across the universe without barriers and ended the "dark age." But light didn't shine through quickly: the process began roughly 680 million years after the Big Bang and ended approximately 1.1 billion years after the Big Bang.

"There's a lot of scientific depth in there, but basically it's trying to figure out how galaxies formed," Williams said of the research. "It was an incredible experience, because I got to both work on the cosmology and the science behind that — and get my hands dirty, helping build this telescope out in the remote desert of western Australia, where there's not a lot of other competing radio sources."

Closer to home, the new NASA astronauts who joined the corps with other expertise are also ready for the new solar eclipse.

New astronaut Jessica Wittner, a naval aviator and test pilot, remembers using solar glasses to watch a solar eclipse at her California elementary school (presumably this was the Jan. 4, 1992 annular "ring of fire" eclipse.) "I love all things space. When it comes to that (solar eclipse), I'm going to be that little kid all over again, when it's happening," she told Space.com.

Fellow naval aviator and new astronaut Jack Hathaway said he's hoping to bring his school-aged kids to the event, as it is so close to Houston: "Hopefully we'll be able to get the opportunity to get to go check it out," he said in another interview. "It's going to be this great opportunity to have first-hand experience of all the wonder that the universe can cause."

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.