Violent mergers might be robbing galaxies of their star-birthing material

A reconstruction of a cosmic crime scene shows that violent galaxy mergers might strip galaxies of their star-forming gas, thereby halting stellar birth.

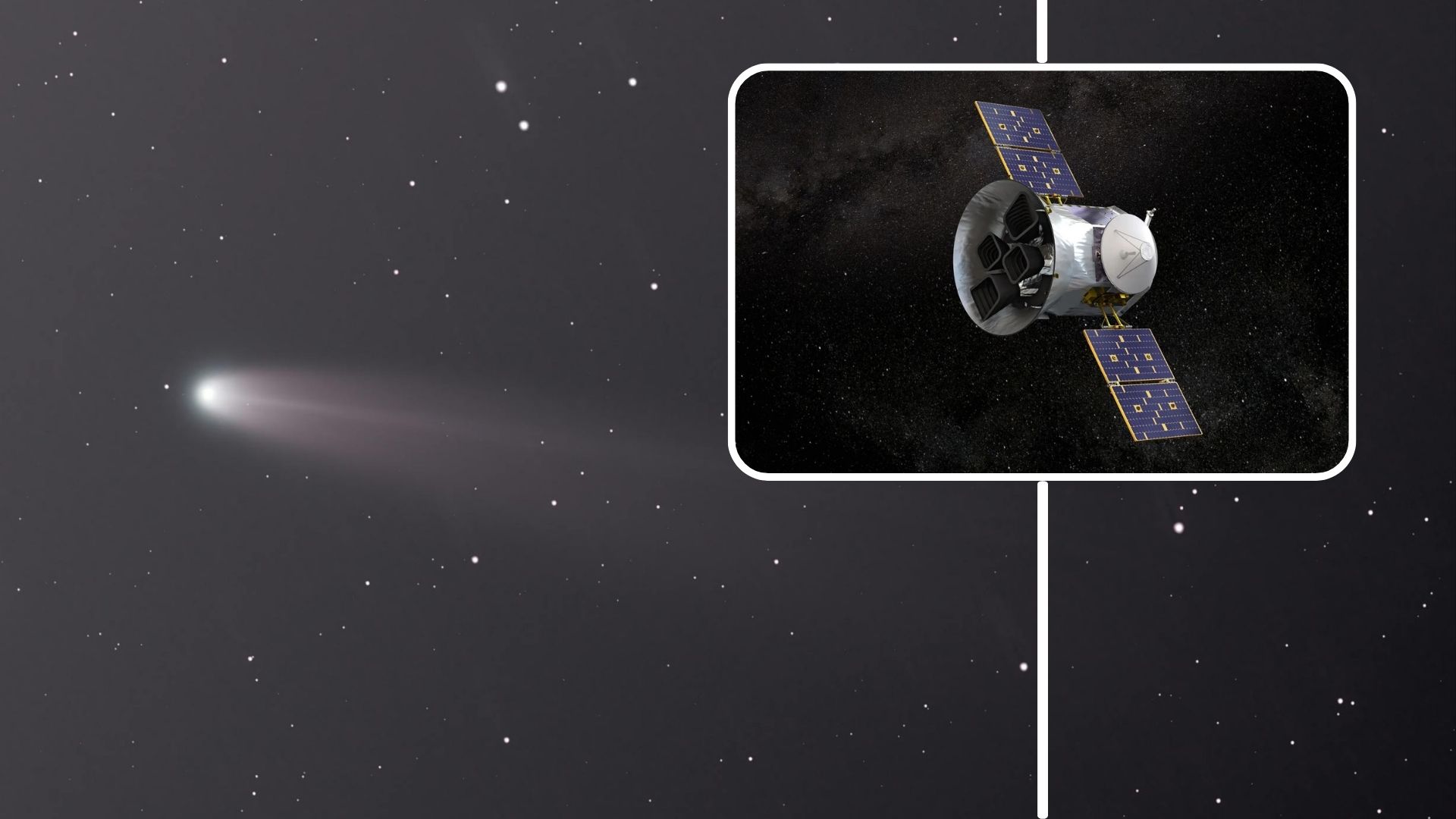

Observations of a violent galactic merger that occurred between 6 and 7 billion years ago could help solve the mystery of how galaxies "die," or stop forming stars.

The unusual features of the dead — or, more accurately, "post-starburst" — galaxy formed by this ancient collision could indicate that these cataclysmic events drive out cold gas. Because this gas is the building block of stellar formation, banishing it effectively "kills" what's left of the galaxy, scientists reported in a new study.

For some time, astronomers have observed that some galaxies form stars at intense rates, while others, such as our own Milky Way, seem to have wound down star birth, or nearly halted the process altogether.

Related: 'Cosmic butterfly' wings shimmer in image of violently colliding galaxies

Exactly why this is the case, however, has remained a mystery, though astronomers do know that the cessation of star formation involves the loss of cold gas. Scientists have proposed possible reasons for this phenomenon, including that supermassive black holes or supernovas "blow away" or heat gas so it can no longer clump together, or that galaxies simply run low on star-forming materials.

"One of the biggest questions in astronomy is why the biggest galaxies are dead," David Setton, a doctoral student in astronomy at the University of Pittsburgh and co-author of the new research, said in a statement. Setton was part of a multi-institutional team that examined this galaxy, with his role being to study the galaxy's size and shape.

New observations of a merger and the tail of gas and dust it ripped from the galaxy it created suggest galactic collisions could play a role in halting star formation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"What we saw is that if you take two galaxies and smash them together, that can actually rip gas out of the galaxy itself," Setton said.

Reconstructing a galactic "murder"

The Milky Way and other nearby galaxies started slowing their production of stars long ago. This means that, to figure out what's causing these galaxies to "die," astronomers need to look farther into space — and thus further back in time — to spot galaxies that have only recently stopped forming stars.

To look for an example of a galaxy with recently quenched star formation, the team used data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, an effort to map millions of galaxies based on observations from a telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico.

The researchers combined these data with observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, a collection of 66 radio telescopes spread across the Atacama Desert in northern Chile. This allowed the team to spot a "post-starburst" galaxy between 6 and 7 billion light-years away that still showed evidence of possessing star-forming cold gas.

"So then we needed an explanation," Setton said. "If it has gas, why is it not forming stars?"

Taking another look at the galaxy with the Hubble Space Telescope, the team spotted a tail of gas created by a merger. Using this unique structure, they reconstructed the violent event and the intense gravitational forces that would have torn gas and stars from the galaxies, hurling them hundreds of millions of light-years — twice the width of the Milky Way.

"That was the smoking gun. We were all so struck by it," Setton said. "You just don't see this much gas this far away from the galaxy." Such events may be fairly common where gravity pulls large objects into dense groups.

"There are all these big voids in space, but all of the biggest galaxies live in the spaces where all of the other big galaxies live," Setton said. "You expect to see these sorts of big collisions once every 10 billion years or so for a system this massive."

Once the galaxy's massive tail peters out, it looks like any other dead galaxy, Setton added. This means other galaxies that have recently ceased star formation may look like this upon closer inspection — a question the researchers aim to investigate further.

The team's research was published online Aug. 30 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.