Dark energy may allow black holes to live in 'perfect pair' binaries

'It seems plausible that our solution could hold true for three or even four black holes, opening up a whole range of possibilities.'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

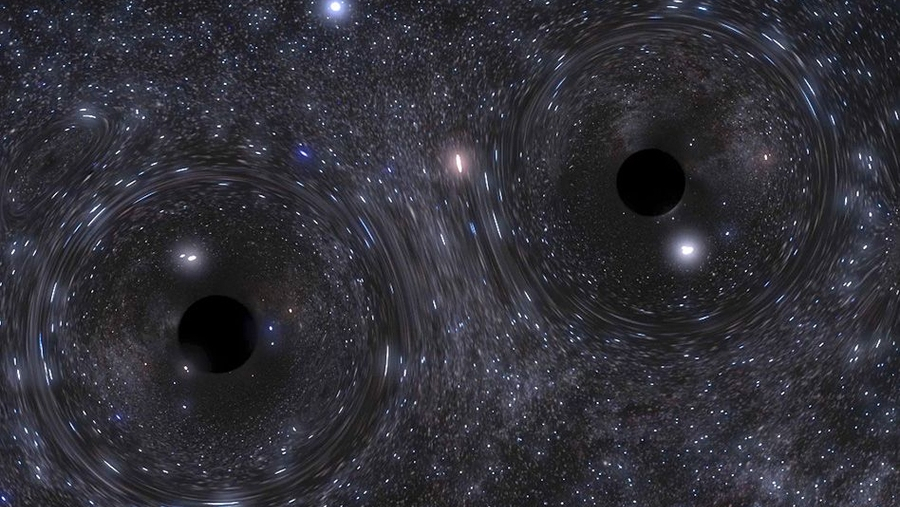

Binary black holes may be more stable than scientists had previously believed, with the action of dark energy accelerating the expansion of the universe and helping black holes in these binaries maintain a safe distance.

Black holes are regions of space around an infinitely dense "singularity" born from the collapse of a massive star. With masses many times that of the sun crammed into widths as small as 10 miles (16 kilometers), black holes have a gravitational pull so strong that not even light can escape a boundary around them, called the event horizon. And because massive stars are commonly found in binary pairs orbiting each other, black holes, too, often come in binary partnerships.

As these black holes move, they create gravitational waves — ripples in the fabric of space-time — and these waves carry angular momentum away from the system. This causes the black holes to spiral together, with gravity eventually taking over, causing the black holes to collide, merge and form a single, more massive black hole. Until now, scientists had thought that process was inevitable — meaning binary black holes are ultimately destined to become single solitary objects.

Related: 1st black hole imaged by humanity is confirmed to be spinning, study finds

That's the case if the universe is static. However, since the early 1900s and the discovery by Edwin Hubble that galaxies are rapidly moving away from each other, scientists have known that the universe is expanding. Additionally, at the end of the 20th century, astronomers discovered that this expansion is actually accelerating, with the cause of the acceleration labeled "dark energy."

Dark energy accounts for as much as 68% of the energy and matter content of the cosmos, though scientists remain in the dark about what exactly it is.

"The standard model of cosmology assumes that the Big Bang brought the universe into existence and that, approximately 9.8 billion years ago, it became dominated by a mysterious force, coined 'dark energy,' which accelerates the universe at a constant rate," University of Southampton professor Oscar Dias, lead author of the new study, said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Is two company for black holes?

The action of dark energy means that black holes sit in an ever-expanding fabric of space-time, leading the team to question if this expansion could help black hole pairings stay separated. They tackled the problem with some complex mathematical models and found that two non-rotating black holes could indeed exist in equilibrium, with the gravitational attraction between them counteracted by expansion.

"Viewed from a distance, a pair of black holes whose attraction is offset by cosmic expansion would look like a single black hole," Dias added. "It might be hard to detect whether it is a single black hole or a pair of them."

On the flip side of that, the gravitational attraction between the binary black holes would prevent the expansion of the universe from pushing the black holes too far apart.

The researchers think that their solution could be expanded to include rotating black holes, known officially as "Kerr black holes," and even more exotic black hole systems with more than two of these objects.

"Our theory is proven for a pair of static black holes, but we believe it could be applied to spinning ones, too," study co-author Jorge Santos, a researcher at the University of Cambridge in England, said in the same statement. "Also, it seems plausible that our solution could hold true for three or even four black holes, opening up a whole range of possibilities."

The team's research was published last month in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.