When and where will China's big rocket debris fall to Earth this weekend?

UPDATE: The rocket has fallen to Earth. Read our full story on the Long March 5B rocket debris reentry.

A big Chinese rocket body will likely crash back to Earth tomorrow (July 30), but nobody knows exactly when or where.

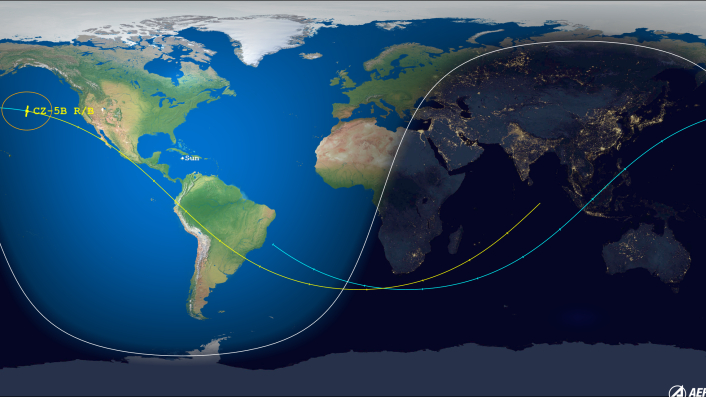

The 25-ton (22.5 metric tons) core stage of a Long March 5B rocket will reenter Earth's atmosphere tomorrow at 12:15 p.m. EDT (1805 GMT), plus or minus 1 hour, according to the latest forecast by researchers at The Aerospace Corporation. The booster has spent less than a week in orbit; it lofted Wentian, the second module for China's Tiangong space station, on July 24.

Most of the rocket body will burn up, but big chunks of it will survive the fiery passage — probably 5.5 tons to 9.9 tons (5 to 9 metric tons), according to The Aerospace Corporation's Center for Orbital Reentry and Debris Studies.

Related: The biggest spacecraft to fall uncontrolled from space

Based on the core stage's orbit, we know those hunks will come down somewhere between 41 degrees north latitude and 41 degrees south latitude. Europe and most of Northern Africa appear to be out of the line of fire, based on the latest forecast. We also know the debris "footprint" will be large, with some pieces likely falling several hundred miles from each other.

But it's tough at the moment to say much more than that, given the imprecision of the reentry window. The rocket body is zooming around Earth at about 17,000 mph (27,400 km/h), after all, so an error of one hour in the predicted reentry time translates to a 17,000-mile error in the location of the footprint.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This imprecision is no indictment of space junk researchers and satellite trackers; forecasting such debris falls is just really, really hard.

"The snag is that the density of the upper atmosphere varies with time; there's actually weather up there," astrophysicist and satellite tracker Jonathan McDowell said during a discussion about the coming Long March 5B crash that The Aerospace Corporation livestreamed on Twitter yesterday (July 28).

"And so that makes it impossible to predict exactly at what point the satellite will have plowed through enough atmosphere to melt and break up and finally reenter," added McDowell, who's based at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

And the Long March 5B core isn't taking a smooth, predictable path through the upper atmosphere, further complicating forecasting attempts.

The rocket body appears to be "tumbling in some fashion, meaning that there's a constantly sort of varying amount of drag that's put on it," Matthew Shouppe, senior director for commercial space at the California-based tracking company LeoLabs, said during yesterday's discussion. "And since we don't know exactly how that's tumbling, we can't model that exactly."

We can make some educated guesses about the rocket crash, however, based solely on geography. For example, the Long March 5B core is likely to reenter over water, because oceans cover more than 70% of Earth's surface. And even a fall over terra firma is unlikely to result in injuries or infrastructure damage, given that most people live in big metropolitan areas that are separated by many miles of open space.

Indeed, there's a "99.5% chance that nothing will happen," Ted Muelhaupt, a consultant with The Aerospace Corporation's Corporate Chief Engineer’s Office, said during yesterday's discussion.

So there's no reason to panic. But feel free to be annoyed that we need to worry at all, for McDowell, Shouppe and Muelhaupt all stressed that the coming crash was very avoidable.

Other orbital rockets don't tend to cause such problems; their big core stages are steered into the ocean or into unpopulated areas shortly after liftoff, or, in the case of SpaceX's Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launchers, come down for vertical landings for future reuse. The Long March 5B core, by contrast, reaches orbit along with its payload and stays aloft until atmospheric drag brings it down in an uncontrolled fashion.

We saw such falls after the Long March 5B's two previous missions, which launched in May 2020 and April 2021. The rocket body fell over empty ocean following the April 2021 liftoff, but the May 2020 mission resulted in a crash that spread debris over parts of West Africa. And some of that spaceflight hardware apparently reached the ground in Ivory Coast.

Editor's note: This story was updated at 7 a.m. ET on July 30 with the latest prediction from The Aerospace Corporation.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.