14 of the biggest spacecraft ever to fall from space

A rundown of some of the biggest spacecraft to smash into Earth beyond their operators' control.

- Europe's GOCE Satellite

- Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS)

- Skylab

- Pegasus 2

- Salyut 7

- Space Shuttle Columbia

- Cosmos 954

- Long March 7 Rocket

- China's Tiangong 1 Space Lab

- Tiangong 2: China's 2nd Space Lab (Controlled)

- Russia's Space Station Mir (Controlled)

- Long March 3B booster crashes near house

- Chinese orbital module

- Bus-sized satellite crash

Prior to the start of the Space Age in 1957, the only objects we had to consider falling from space were meteors, asteroids, and the occasional comet.

Today, however, with satellites and spacecraft frequently being launched into orbit and beyond, some of these objects eventually return to Earth. Here’s a look at some of the largest spacecraft to re-enter from space.

Editor's note: Russia's Mir space station is included here as a reference for comparison (due to its massive size), but it was intentionally deorbited in a controlled manner in 2001.

Europe's GOCE Satellite

The European Space Agency's GOCE satellite fell to Earth on Nov. 10, 2013, to meet a fiery doom during re-entry.

The gravity-mapping GOCE satellite weighed about 1 ton and was about 17 feet long (5.3 meters). That's pretty big, but much larger satellites have made uncontrolled re-entries over the years.

Full Story: 1-ton European Satellite Falls to Earth in Fiery Death Dive

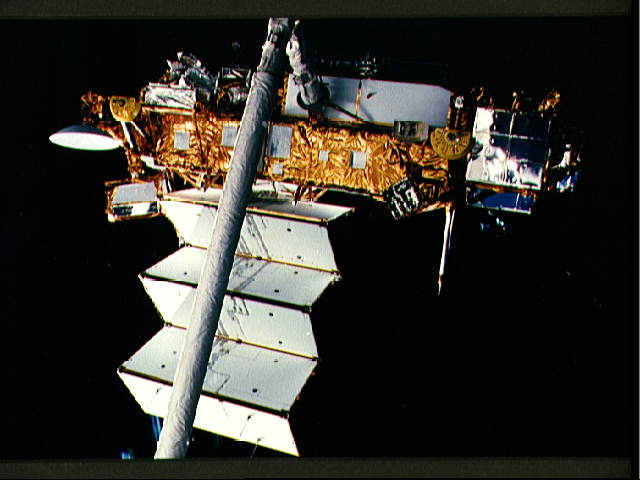

Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS)

The 6.5-ton UARS satellite was 35 feet (10.7 m) long and 15 feet (4.5 m) wide. NASA's space shuttle Discovery deployed the climate satellite in September 1991 on the orbiter's STS-48 mission.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

UARS studied Earth's atmosphere for 14 years, measuring many key chemicals that are still being tracked by other craft today. UARS also provided important information about the amount of light that comes from the sun at ultraviolet and visible wavelengths. The $750 million satellite was decommissioned by NASA in December 2005 and fell to Earth in September 2011.

Researchers estimated that about 1,170 pounds (532 kilograms) of UARS' 6.5-ton bulk likely survived re-entry.

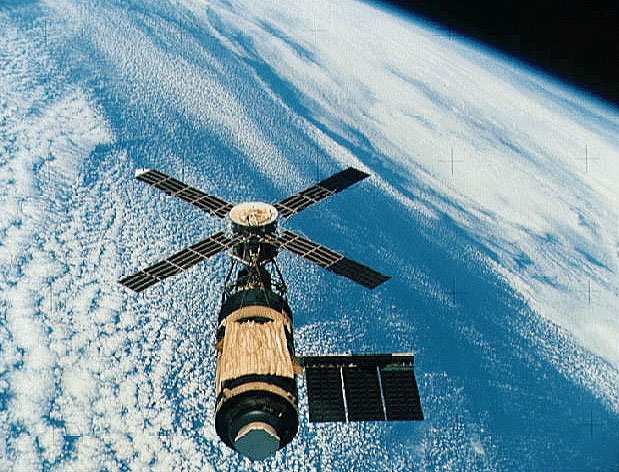

Skylab

NASA launched the Skylab space station in 1973, and a total of three crewed missions visited the 85-ton space station in 1973 and 1974. NASA originally envisioned Skylab to stay in orbit for a decade or so, but that didn't happen. Higher-than-expected solar activity heated and expanded Earth's atmosphere, increasing the drag on Skylab. By the middle of 1979, it was ready to come down. There wasn't much NASA could do to control the outpost's re-entry, but the space agency was able to manage some of Skylab's tumbling maneuvers.

On July 11, 1979, Skylab returned to Earth, burning up over the Indian Ocean and Western Australia. Some large chunks survived re-entry, making landfall southeast of Perth and elsewhere. Nobody was hurt, but the Australian town of Esperance charged NASA $400 for littering.

NASA, however, never paid up. A California radio DJ took care of the fine in 2009 after collecting donations from his listeners.

Pegasus 2

NASA launched the 11.6-ton Pegasus 2 satellite in 1965 to study the abundance of micrometeoroids in low-Earth orbit.

Pegasus 2 gathered data and beamed it home for about three years, then zipped around Earth for another 11 years, during which time its orbit got progressively lower and lower. The satellite finally came down on Nov. 3, 1979, but the debris splashed down harmlessly in the mid-Atlantic Ocean.

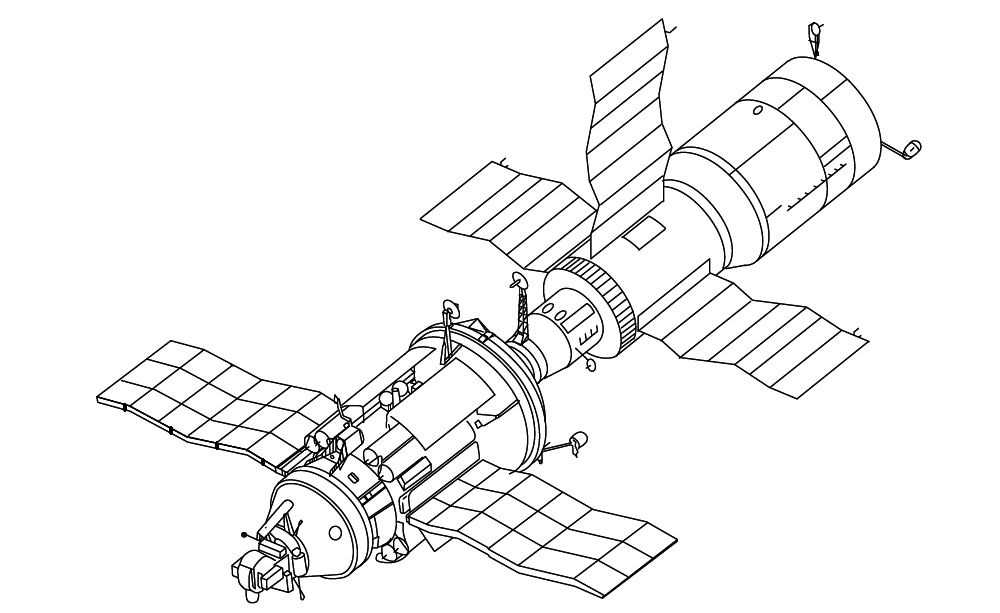

Salyut 7

Salyut 7 was the last of nine space stations the Soviet Union launched under its Salyut program from 1971 to 1982. Salyut 7 blasted off on April 19, 1982, and stayed aloft for nearly nine years, harboring six different resident crews during its operational life.

Salyut 7 was about 52 feet (16 meters) long and 13.6 feet (4.15 m) across at its widest point. The total mass of the outpost was about 22 tons.

The uncrewed space station came barreling back to Earth on Feb. 7, 1991. At the time, a spaceship called Cosmos 1686 was docked to Salyut 7, to help test the attachment of expansion modules to space stations. Cosmos 1686 was also uncrewed, and it tipped the scales at about 22 tons as well.

The huge Salyut 7-Cosmos 1686 complex burned up and broke up over Argentina, with some debris scattering over a town called Capitan Bermudez. There were no reported injuries.

Space Shuttle Columbia

Tragically, NASA's space shuttle Columbia also made an uncontrolled return to Earth at the end of its STS-107 mission in 2003.

On Feb. 1, 2003, Columbia broke apart over Northeastern Texas as it returned home from a 16-day science mission. All seven astronauts aboard were killed, and the 100-ton orbiter was destroyed.

Photos: Remembering the Columbia Space Shuttle Tragedy

An investigation later cited heat shield damage to the leading edge of Columbia's left wing as the cause of the disaster. A piece of foam insulation from Columbia's external fuel tank broke off during launch and punched a hole in the shuttle's wing 82 seconds after liftoff on Jan. 16, 2003.

The damage allowed super-hot plasma from the spacecraft's atmospheric entry to penetrate Columbia's left wing, destroying the vehicle as it headed to its landing site at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Nobody on the ground was hurt, but the loss of Columbia marked the second fatal disaster of NASA's 30-year shuttle program.

Cosmos 954

Though this Soviet spycraft was not the biggest uncrewed satellite to crash to Earth, it may have been the scariest.

The 8,400-pound (3,800 kg) Cosmos 954 launched in September 1977 on a mission to track the movements of U.S. nuclear submarines. Cosmos 954 itself was nuclear-powered, and its reactor core failed to separate and boost the spacecraft to a higher, nuclear-safe orbit as planned. That made the satellite's out-of-control re-entry, on Jan. 24, 1978, a cause for global concern. Cosmos 954 came back to Earth over Northwestern Canada, spreading radioactive debris over a wide area. The Canadian government billed the Soviet Union $6 million to cover the cost of the search and cleanup efforts; the Soviets eventually paid $3 million.

Several other nuclear-powered Soviet satellites have plummeted to Earth, including Cosmos 1402 in 1983.

Long March 7 Rocket

The 6-ton second stage of China’s Long March 7 rocket fell back to Earth on July 27, 2016, causing a spectacular fireball in skies across the western United States.

The Long March 7 had lifted off on its maiden flight on June 25, toting a prototype crew capsule and various technology demonstrations to orbit, Chinese officials said.

China's Tiangong 1 Space Lab

On April 1, 2018, China's Tiangong 1 space laboratory fell out of the sky, breaking apart and burning up in the skies over the southern Pacific Ocean at about 8:16 p.m. EDT (0016 April 2 GMT), according to the U.S. Strategic Command's Joint Force Space Component Command.

Tiangong-1 was about 34 feet long by 11 feet wide (10.4 by 3.4 meters), and it weighed more than 9 tons (8 metric tons). The space lab consisted of two main parts: an "experimental module" that housed visiting astronauts and a "resource module" that accommodated Tiangong-1's solar-energy and propulsion systems.

China launched Tiangong 1 into orbit on Sept. 29, 2011. It flew about 217 miles (350 kilometers) above Earth and hosted astronaut crews from China's Shenzhou 9 and Shenzhou 10 missions in 2012 and 2013, respectively. After those missions, the primary goals for the lab, which had a two-year-lifespan, were complete.

In March 2016, Chinese flight controllers lost contact with Tiangong 1 and it was allowed to fall from space.

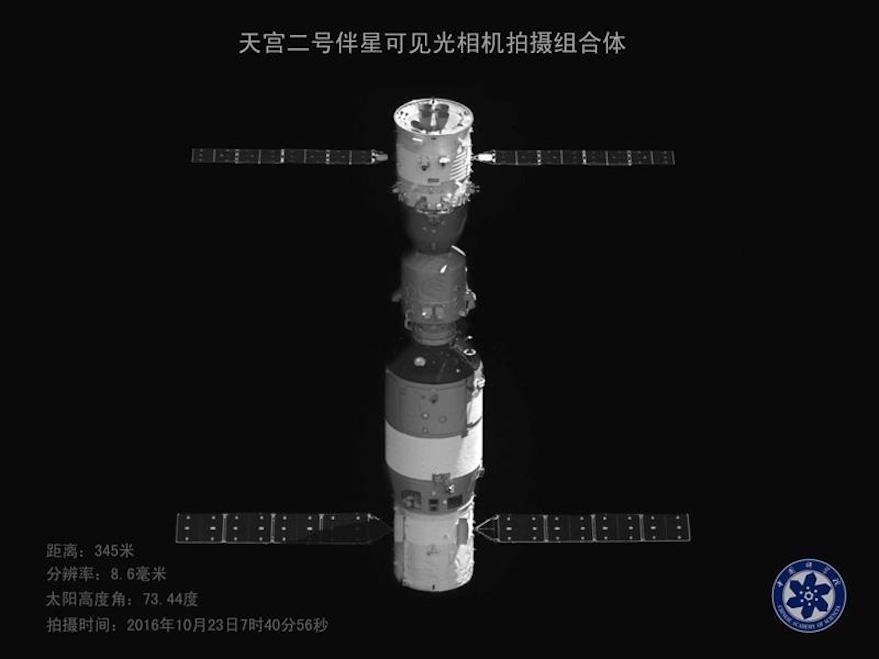

Tiangong 2: China's 2nd Space Lab (Controlled)

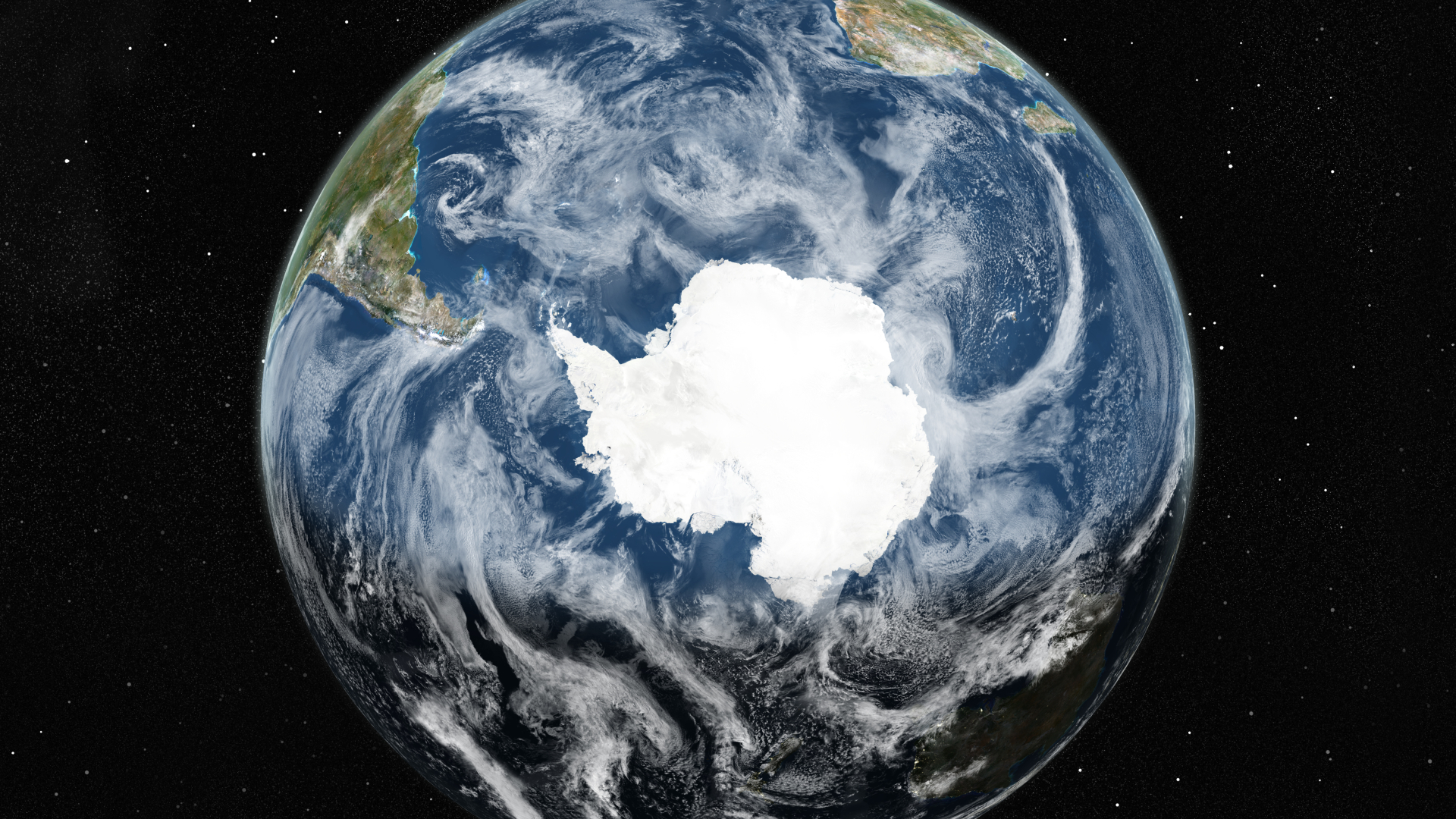

China's second space lab, Tiangong 2, fell to Earth on July 19, 2019. Unlike its Tiangong 1 predecessor, Tiangong 2's re-entry was controlled.

The 8.6-metric-ton Tiangong 2 reentered over the South Pacific Ocean Uninhabited Area, a dumping ground for defunct spacecraft. Tiangong-2 launched in September 2016 and was used by China to test life support, refueling and resupply capabilities to support the development of a larger, 20-ton space station.

In September 2018, the China Manned Space Engineering Office announced the Tiangong 2 space lab would be deorbited in 2019 to end its mission.

Related: China's Tiangong 2 Space Lab in Pictures

Russia's Space Station Mir (Controlled)

One of the largest spacecraft ever to re-enter Earth's atmosphere remains the massive Mir space station, which was deorbited by Russia on March 23, 2001.

Unlike most other falling spacecraft on this list, Mir's re-entry was a completely controlled descent aimed at disposing of the iconic Russian space station in the Pacific Ocean. Because of Mir's immense size, it is included in this list for reference.

Russia's Mir space station consisted of several cylindrical modules launched separately and assembled in orbit between 1986 and 1996. By 2001, Mir (whose name meant "Peace" or "Community" in Russian) weighed 135 tons and spent 15 years in space.

Mir was as large as six school buses and, with the exception of two periods without a crew, was continuously inhabited until August 1999.

Mir re-entered the Earth's atmosphere near Nadi, Fiji, and fell into the South Pacific.

Long March 3B booster crashes near house

On Dec. 25, 2023, the China National Space Administration launched two satellites from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in Sichuan province.

The satellites were successfully placed into medium Earth orbit but the side boosters of the Long March 3B multistage launch vehicle fell back to Earth and landed in South China’s Guangxi region.

Read more: Chinese rocket booster falls from space, crashes near house, after satellite launch: report

Chinese orbital module

On April 2, 2024, a flaming piece of Chinese space junk crashed to Earth over Southern California.

The reentry created an impressive blazing fireball seen by people from the Sacramento area all the way down to San Diego, according to the American Meteor Society (AMS).

The debris responsible was the orbital module of China's Shenzhou 15 spacecraft, and weighed about 3,300 pounds (1,500 kilograms).

Bus-sized satellite crash

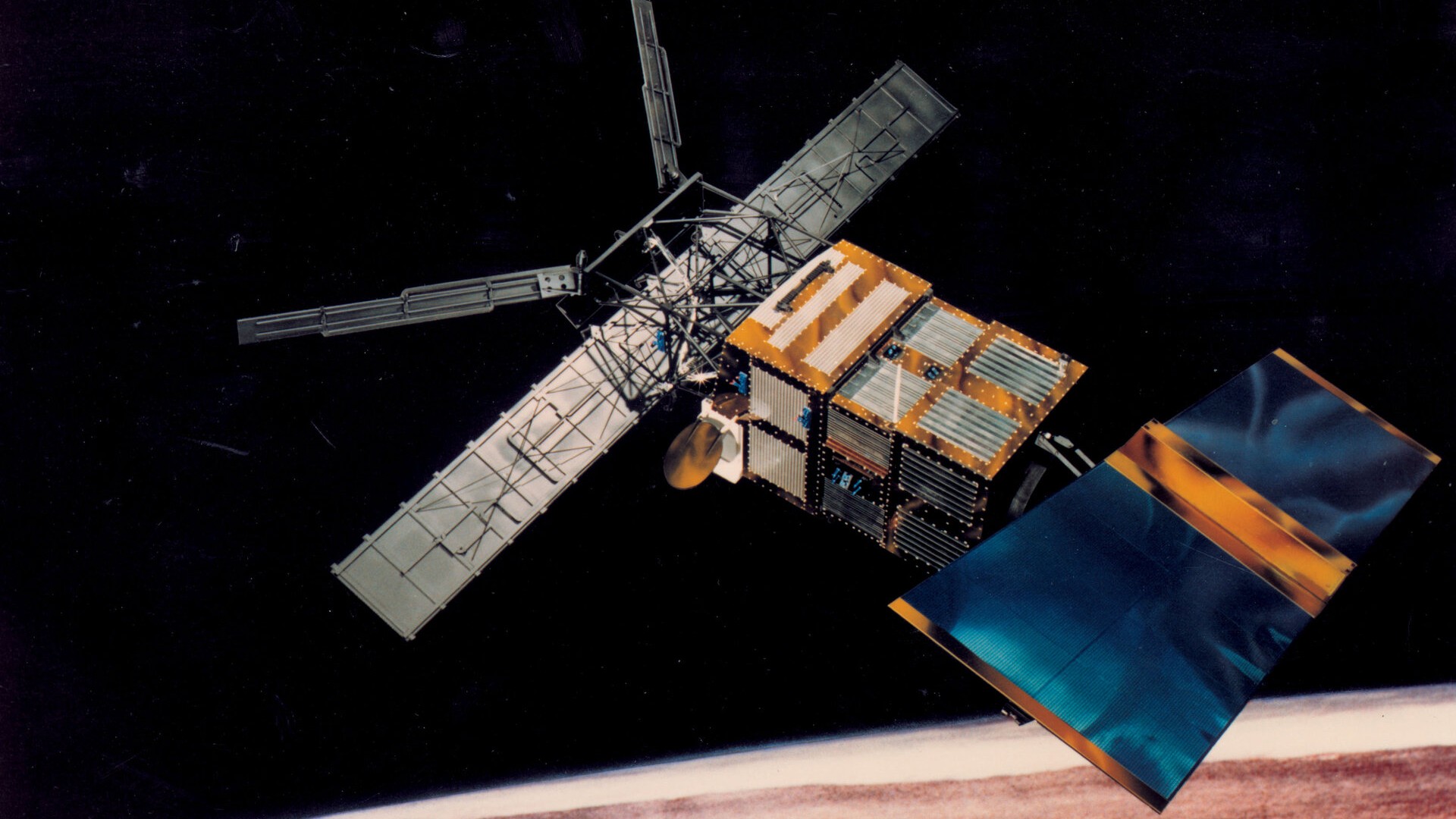

On Feb. 21, 2024, a bus-sized satellite fell back to Earth, marking the end of its nearly 30-year life in space.

The European Space Agency's (ESA) European Remote Sensing 2 (ERS-2) satellite reentered Earth's atmosphere at 12:15 EST (1715 GMT) over the Pacific Ocean. The fall ended a nearly 13-year deorbiting campaign that began with 66 engine burns in July 2011, depleting the spacecraft of remaining fuel.

Read more: Bus-sized European satellite crashes to Earth over Pacific Ocean

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

- Daisy DobrijevicReference Editor