Tiangong-1: China's First Space Station

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Tiangong-1 is a single-module space station operated by the China National Space Administration. The module was launched in 2011 and hosted two crews of taikonauts (Chinese astronauts) in 2012 and 2013. Since China's space agency discloses less information about its missions than other space agencies, the details surrounding the space station are not widely known.

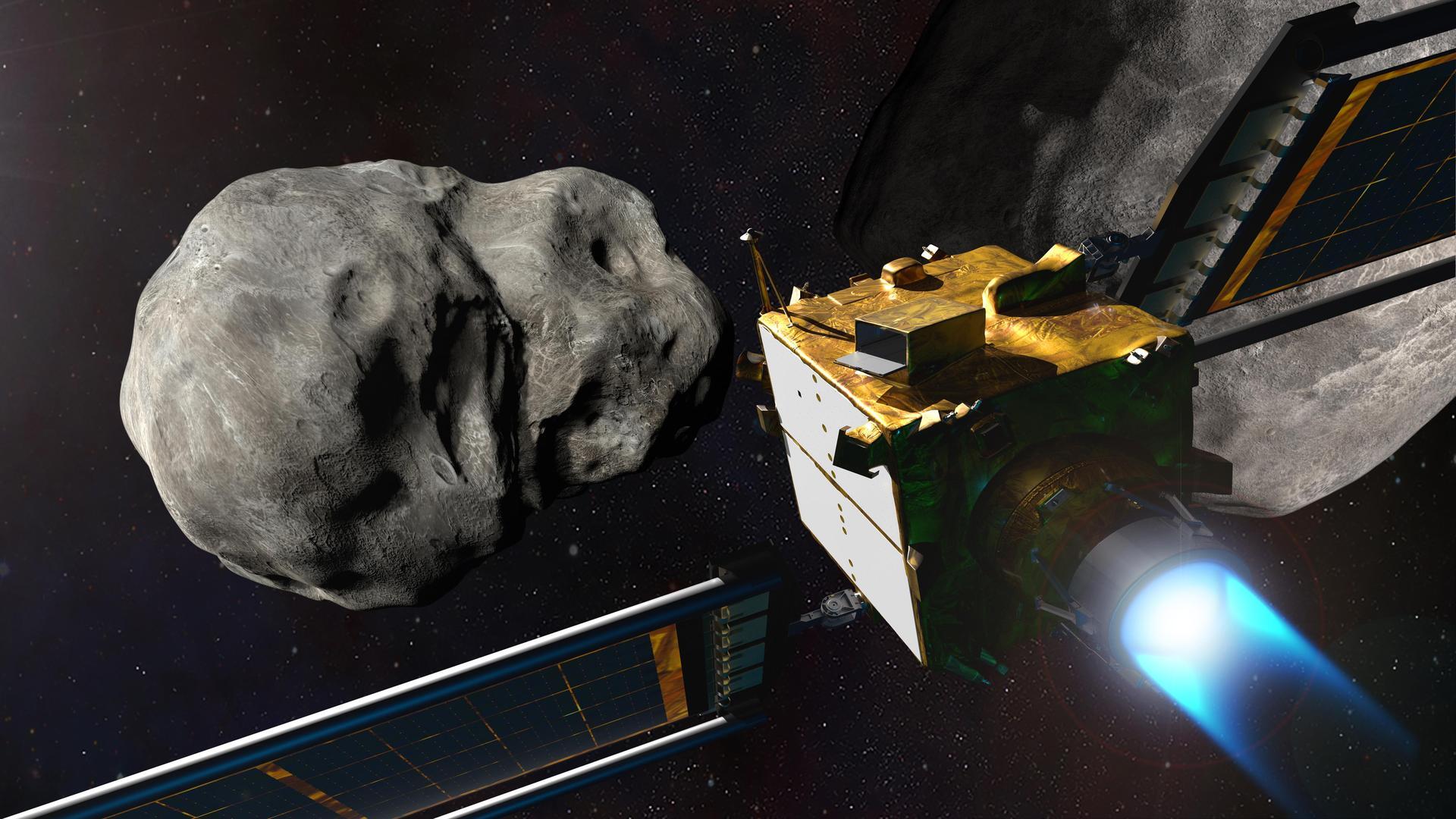

In 2016, Chinese flight controllers lost control of Tiangong-1, sealing the 8.5 metric ton space lab's fate. Tiangong-1's decaying orbit may make it fall into Earth's atmosphere sometime between March 30 and April 2, 2018.

Chinese Space Station's Crash: Everything You Need to Know

Article continues below"There is a chance that a small amount of Tiangong-1 debris may survive reentry and impact the ground. Should this happen, any surviving debris would fall within a region that is a few hundred kilometers in size and centered along a point on the Earth that the station passes over," according to the U.S.-based Aerospace Corporation, which is tracking Tiangong-1.

The orbit of the space station passes over most of the civilized world, with the exclusion of northern latitudes that include the United States, Russia and Canada, as well as the extreme south of the world, including Antarctica and the tip of South Africa. However, most of the Earth is covered by water, reducing the chances of a crash in a populated area.

Preparing for orbit

Multiple news sources say the Chinese were interested in having a human space program back at the dawn of the Space Age in the 1950s and the 1960s. At the time, the United States and the Soviet Union were competing for supremacy in orbit, sending up satellites (starting in 1957) and people (starting in 1961). The space race cooled in the late 1960s after the United States landed people on the moon, and the two nations agreed to their first joint space mission, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, which flew in 1975.

Meanwhile, China was secretly working on its own single-person space capsule known as Shuguang-1. Chinese sources translated for Encyclopedia Astronautica suggest that China got as far as selecting 19 astronauts for the program before its cancellation in 1972, for political reasons. More studies on human spacecraft reportedly took place in the 1980s and 1990s.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Shenzhou program had its first successful robotic launch in 1999, and the first known taikonaut, Yang Liwei, flew on a 21-hour space journey on Oct. 15, 2003, aboard Shenzhou 5. This made China only the third country to independently launch humans into space. In 2005, China launched its first two-person mission. In 2008, China launched a three-person mission into space and performed its first spacewalk.

From there, a probable path was to follow the lead of other nations that had established space stations, namely the Soviet Union (Salyut series and Mir), the United States (Skylab) and the consortium of 15 nations (led by the United States and Russia) that created the International Space Station. So on Sept. 29, 2011, China launched Tiangong-1 on a Chinese Long March 2F rocket from northwest China.

Visiting the laboratory

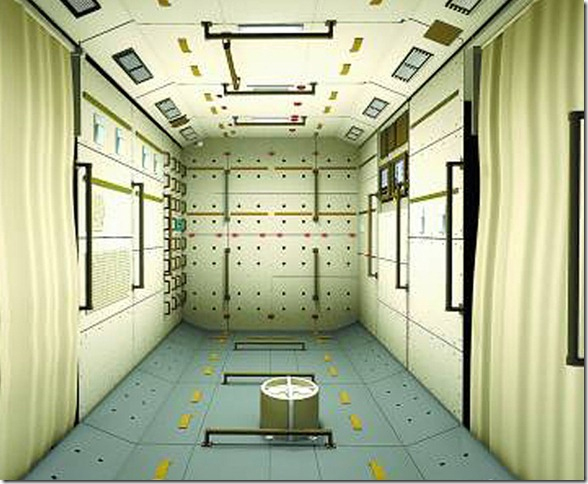

Tiangong-1 (whose name means "Heavenly Palace") weighs about 8.5 metric tons, and is about 34 feet long by 11 feet wide (10.4 meters by 3.4 meters). It contains an experiment module — where the astronauts live and work — and a resource module that contains propellant tanks and rocket engines.

The module was placed in low Earth orbit at about 217 miles (350 kilometers), at a slightly lower altitude than the International Space Station. Two solar arrays power the station, and it can house three astronauts.

A primary goal for the module was to help the Chinese practice space dockings, which is an important skill for nations looking to build larger space stations or to send multiple spacecraft to the moon, Mars or other locations in the solar system.

In China's case, Liwei said around the time of the launch, the country wanted to practice these skills to create a multi-module, 60-ton space station in low Earth orbit for operation in the 2020s. In April 2017, Chinese officials predicted the first module for this space station would launch in 2019, according to Reuters.

As Tiangong-1 was initially slated to last two years, a suite of space missions quickly followed its launch. First came Shenzhou 8, an uncrewed spacecraft that docked with the space station in October 2011. Two crews followed. June 2012's Shenzhou 9, a three-person crew, included the first Chinese woman in space. A second three-taikonaut crewed docking took place in June 2013, with Shenzhou 10.

Space stations after Tiangong-1

A second space station, Tiangong-2, launched on Sept. 15, 2016, to further test out space station technologies. A crewed docking mission, Shenzhou 11, visited the space station in October and November 2016. The Chinese then tested out docking and refueling with a cargo ship, called Tianzhou-1. The cargo spacecraft made three dockings in April, June and September in 2017. The last docking was performed in just 6.5 hours instead of two days, according to GBTimes.com. The status of Tiangong-1 is unclear, according to a Space.com article from June 2016. China released little information about Tiangong-1 during its mission. Some experts examining its trajectory suggest it might be in an uncontrolled orbit, while others have seen evidence of reboosting and believe the spacecraft could fly for a while.

While crews have not visited Tiangong-1 since 2013, data gathered using the station has helped the Chinese find minerals and monitor ocean and forest use. It also helped with emergencies such as China's Yuyao flood disaster in 2013, according to the China Manned Space Engineering (CMSE) office. State-run news reports from China said the data collection ceased in March 2016.

It's unclear if and when Tiangong-1 will return to Earth, and if Chinese space officials will have control over its re-entry trajectory. While some past space stations (such as Mir) were brought down in a controlled fashion, others have tumbled back to Earth. The most notorious uncontrolled re-entry was Skylab in 1979, which saw some pieces crash into populated areas in western Australia.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.