Are China's moon missions a threat to the US? Space experts don't think so

U.S. fears that China could set up a moon base for spying do not line up with the country's statements about its space program, according to security experts.

China's work in space has hit headlines these past few months as NASA's authorization bill for fiscal year 2020 proceeds through the government's approval process. The House version of the bill, passed in late January, calls for the National Security Council "to coordinate an interagency assessment of the space exploration capabilities of the People's Republic of China," including both "any threats to United States assets in space" and China's plans to partner with other countries.

Although the bill does not mention moon activities specifically, Rep. Doug Lamborn, R-Colo., told delegates at the Space Foundation's State of Space conference in February that he is worried about the security implications if China has a permanent presence on the moon.

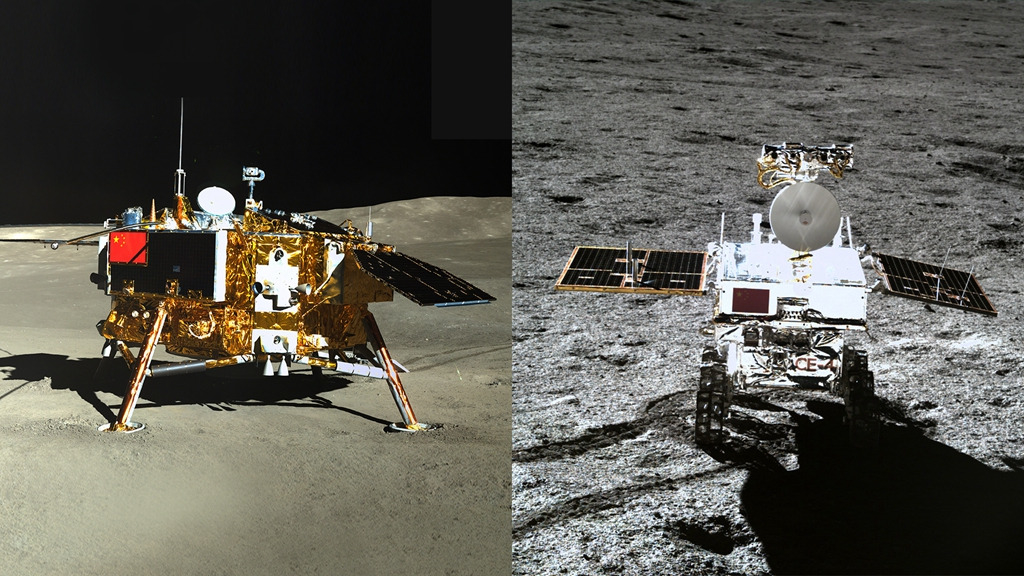

Related: Chang'e 4 in pictures: China's mission to the moon's far side

"They very much have military thoughts in mind when it comes to what they can do with a military presence on the moon, and the ability to see things and track things with the unchanging platforms that no one really has right now," Lamborn said at the conference, referring to media reports from 2019 that the Chinese may be considering establishing a robotic base at the moon's south pole.

China is indeed busy building up lunar capabilities, particularly after the success of the Chang'e-4 mission to the far side of the moon that includes a rover and a lander, which touched down in January 2019. China is also planning a sample-return mission known as Chang'e 5, scheduled to lift off in 2020 and land in Oceanus Procellarum. An overview of the nation's moon plans published in Science last year suggests that Chang'e 6 will return samples and Chang'e 7 will examine the lunar south pole's environment and resources. Both Chang'e 6 and Chang'e 7 are expected to lift off in the 2020s.

And China does not separate its scientific and military space programs as the U.S. does, with NASA being a strictly civilian agency. Instead, the China National Space Administration is a branch of the Chinese military. So when media reports emerged in October that China was building a spacecraft outside sources say may be capable of carrying humans to the moon, some worried that the transition from robotic to human exploration could pave the way for a more military focus at the moon.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But this ambitious robotic lunar plan does not seem like a military threat, according to an expert on China's space program. "It may, in the minds of some Americans, present some sort of geopolitical or psychological challenge," Gregory Kulacki, the Union of Concerned Scientists' China project manager for the global security program, said in an email to Space.com. "But I find it difficult to see how a Chinese landing on the moon is threatening to the United States or any other nation."

Right now, there are few opportunities for NASA to collaborate with China, since a congressional mandate has banned the agency from cooperating with China without prior approval since 2011. But Kulacki said the U.S. should consider collaborations in space with China. There is a precedent: NASA and the Soviet Union had many scientific collaborations during the Cold War, including a joint human mission called the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975.

But the Soviet Union was interested in partnering in low Earth orbit; China may not be. Its human spaceflight goals are based on a blueprint first set out in the 1980s under a program known as Project 921, Dean Cheng, a research fellow for Asian Studies at the Heritage Foundation, told Space.com. The project calls for a Chinese ability (not a multinational ability, he emphasized) to send a person into orbit around Earth. China further set out its goals in five-year plans, the current of which runs through 2021.

So far, Cheng said, China's five-year plans have closely followed Project 921 and no human visits to the moon have been envisioned so far. Today, the program features the Earth-orbiting Shenzhou spacecraft (which fly roughly every two years) and a series of small space stations called Tiangong, which have seen occasional visits by taikonauts, Chinese astronauts.

"We in the West … speculate that presumably these programs will merge somewhere along the line," Cheng said, referring to the Earth-orbiting human program and the lunar robotic program. "You get lots of speculation about how, where, what, and when, but as far as I know, we have never seen a Chinese official statement that they are going to the moon [with humans]."

And if China does shift its human-exploration focus to the moon, how soon would they try to land? Nowhere near as quickly as the U.S., which is trying to land people on the moon's south pole in 2024, according to Cheng. He said there is "no reason" to think a landing would happen between 2021 and 2026, as China's heavy-lift rocket that presumably would be used for human moon missions — the Long March 5 — has not yet been approved to carry humans.

A crewed lunar mission in the late 2020s is possible, he said, but "extraordinarily ambitious" given that China currently launches people into space every two years and has not gathered the detailed information on human performance in space that it would want before embarking on more far-ranging flights.

"What that would suggest is a 2031 to 2035 time frame," Cheng said. "But that's Dean Cheng's opinion. There is no official Chinese policy."

- This is China's new spacecraft to take astronauts to the moon (photos)

- China releases huge batch of amazing Chang'e-4 images from moon's far side

- This is the 1st photo of China's Mars explorer launching in 2020

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.