Apollo-Soyuz Test Project: Russians, Americans Meet in Space

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

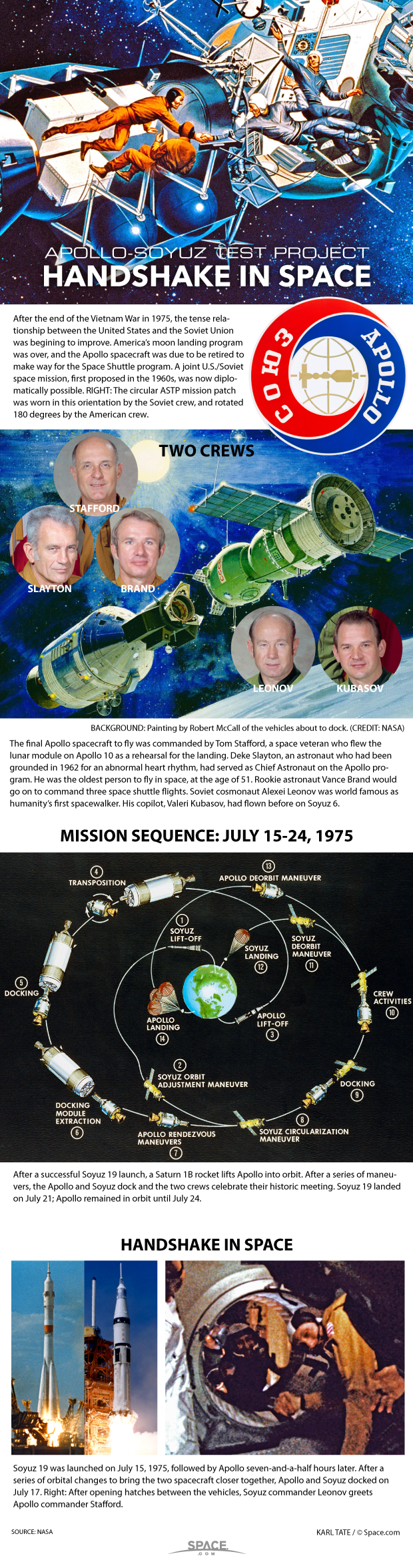

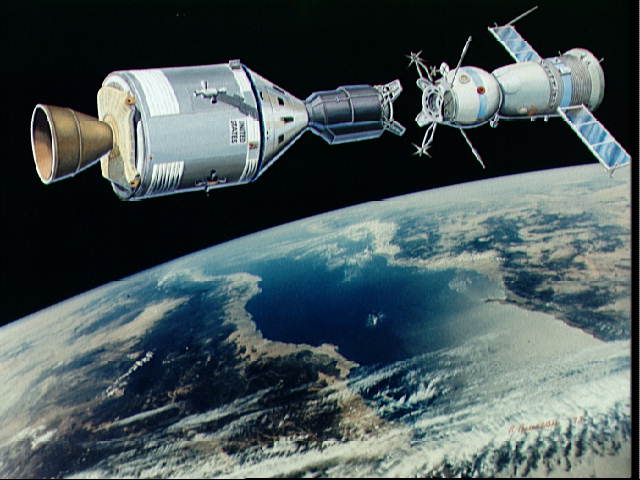

The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project was the first spaceflight to include two participating nations working together with their own national spacecraft. The Americans sent up an Apollo command module, while the Russians launched a Soyuz spacecraft.

The Soyuz and Apollo spacecraft docked on July 17, 1975, in a demonstration of how well the rendezvous and docking systems of each spacecraft would work with each other. The combined crew of five people — three Americans, two Soviets — spent about two days in orbit working on experiments and conducting joint press conferences.

ASTP was a signal that the Space Race was over. The two nations, now fighting different foes other than themselves and facing budgetary restrictions for spaceflight, openly spoke of working together in future initiatives.

This mission laid the groundwork for initiatives such as the Mir-Shuttle program of the 1990s, and the International Space Station that was completed in 2011.

Dealing with cultural differences

ASTP came after years of cold relations between the United States and Russia. President John F. Kennedy famously started the race for the moon in 1961 as a way to beat the Russians in something. The two countries sparred over communism, nuclear arms and other policy matters in the years following.

As the years lengthened, though, relations between the countries improved. At a Paris Air Show a few years before ASTP, astronauts from the United States and cosmonauts from the Soviet Union had met and had a great time together, crew member Vance Brand said in a 2000 oral interview with NASA.

Behind the scenes, NASA, the State Department and the Russian Academy of Sciences pursued a mission that would let the countries cooperate in space. Beyond the technology, it would also be a demonstration to the world of peace and shared purpose.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Still, Brand acknowledged that there were some tensions between the two countries at the beginning.

"We thought they were pretty aggressive people and, I won’t say monsters, but they probably thought we were monsters," Brand said. But he characterized the situation as temporary.

"We very quickly broke through that, because when you deal with people that are in the same line of work as you are, and you’re around them for a short time, why, you discover that, well, they’re human beings."

He added, "They were probably a more secretive society partly because their population had been overrun by invasions for a thousand years. You know, in this country we don’t have that experience or that burden, so we tend to be much more open as a people."

Training overseas

For the Americans, there were months of Russian language training and flying between the two countries to become familiar with the Soyuz system. The Soviets also learned English and visited NASA.

Commander Deke Slayton said the rooms the Americans used in the Soviet Union were bugged, but after a while the crew learned to use them to their advantage.

"One day we decided to test it, and complained loudly that we didn't have anything to do. 'Too bad we don't have a pool table.' The next day, by God, there was a pool table in our bar downstairs," he wrote in his autobiography, "Deke!"

When the Americans got a tour of the Baikonur Cosmodrome – the facility where the Soviets launched every human spaceflight since Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space — Slayton spoke positively of the professionalism of the people working at the facility. It had been closed off to Americans, for the most part, before then.

"It was a very efficient system," Slayton wrote of the Soviet's spacecraft assembly building. "The whole thing was a little cruder than ours — with much less emphasis on keeping stuff 'clean' ... but it worked."

Reaching orbit

When the crews worked together in orbit, they agreed to each speak the other's language: the Soviets spoke English, and the Americans spoke Russian, said crew member Tom Stafford.

This idea originated during training when Stafford and backup commander Anatoliy Filipchenko were practicing communicating during some time off. By Stafford's recollection, it wasn't going so well until he suggested: "Look, I'll speak Russian to you, and you speak English to me. Maybe we can understand it better."

"So we started," Stafford said in a 1997 interview with NASA, "and, boy, it worked slick as a whistle. So we had a couple more drinks, and it even started working better," he added with a chuckle.

The men's activities in orbit drew praise from both nations, including a Soviet radio announcer who proclaimed ASTP "a forerunner of future international orbital stations," according to NASA.

Long after the mission, crew members Tom Stafford and Alexei Leonov — who had made their careers in a space race that strived to outdo the other nation — found themselves as very close friends.

"He's a very outgoing guy, and he's like a brother to me now," Stafford said.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.