How NASA's Apollo Astronauts Went to the Moon

How NASA's Apollo Astronauts Went to the Moon

From 1967 to 1972, several crews of astronauts either prepared for lunar missions or landed on the moon itself as part of NASA's Apollo program. Going to the moon required the support of thousands of people on Earth, including those building all the hardware supporting the astronauts. Here are some of the main pieces of equipment that crews used, along with how they got to the moon, step by step.

Related: Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing Mission

Saturn V rocket

The Saturn V rocket was the 363-foot-tall (111 meters) booster that hefted three crewmembers and all their equipment into Earth orbit in preparation for flying to the moon. The rocket had a mass of more than 6 million lbs. (about 3 million kilograms). It generated about 7.6 million lbs. (34.5 million newtons) of thrust during launch, which NASA says is 85 times the power generated by the Hoover Dam.

The Saturn V was developed at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The rocket was used for every crewed Apollo flight except Apollo 7, which was the first test in orbit of the Apollo command-module spacecraft. Of course, the Saturn V also flew missions near the Earth. It first launched in 1967 for Apollo 4, an uncrewed test flight. The rocket's last launch, also without astronauts onboard, was in 1973, to loft NASA's Skylab space station into Earth orbit.

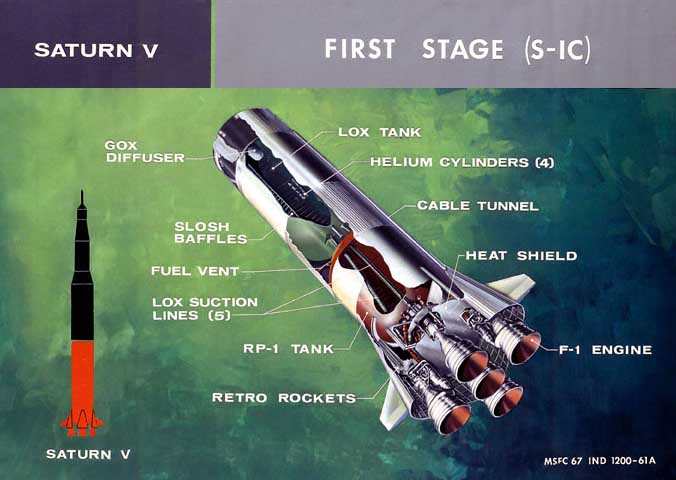

First stage of a Saturn V rocket

The Apollo Saturn V's first stage, known as the S-IC, did most of the heavy lifting to propel the astronauts off Earth. Incredibly, this powerful stage, which included five F-1 engines, burned its fuel for only about 2.5 minutes, bringing the spacecraft and its crew to roughly 38 miles (61 kilometers) in altitude. Once the first stage exhausted its fuel, it would separate and fall back to Earth.

Second stage of Saturn V rocket

The second stage of the Apollo Saturn V, called the S-II, brought the astronauts closer to their final orbit. This stage burned for about 6 minutes, beginning immediately after the first stage completed its work. Powered by five J-2 engines, the second stage brought the astronauts to about 115 miles (185 km) in altitude. That means the stage carried the astronauts across the Kármán line, the internationally defined boundary of space, set at 62 miles (100 km) in altitude.

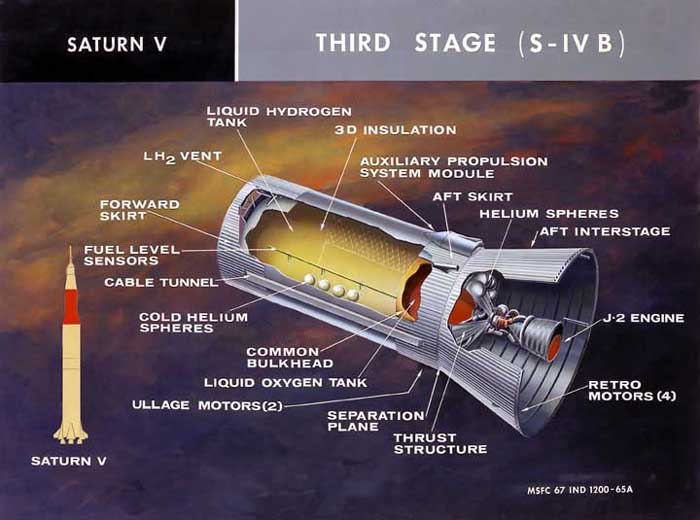

Third stage of Saturn V rocket

The S-IVB was the third and final stage of the Saturn V rocket. When the rocket was headed to the moon, this stage fired twice. The first time was during launch: Moments after the S-II second stage shut down, the S-IVB would take over and bring the astronauts into Earth orbit. The engine's second fire powered a maneuver called the translunar injection, which carried astronauts toward the moon.

Command module

The command module was the spacecraft astronauts depended on to leave Earth and to return home. Its full name, the command and service module, recognizes that it was divided into two main sections: the command module, which carried the astronauts, and the service module, which housed the power and consumables (such as oxygen) that would supply the astronauts during their journey.

While the command module is most famous for lunar missions and their preparations, in 1975, the spacecraft was part of a more diplomatic journey: to dock with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft as part of the Apollo-Soyuz mission. This collaboration between the United States and the Soviet Union was the first part of a long journey that resulted in the International Space Station, which is led by the U.S. and Russia, with many other participating nations.

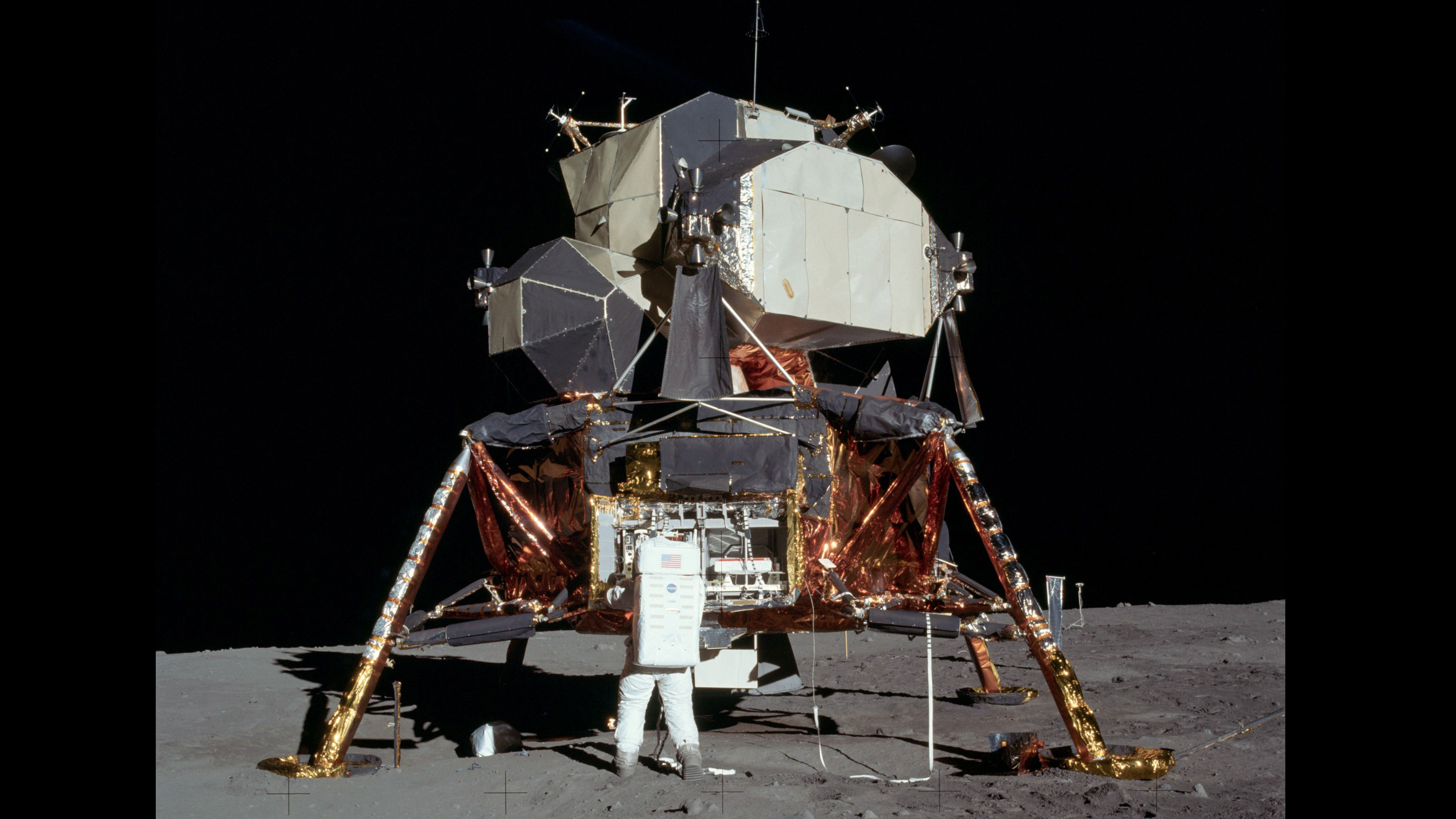

Lunar module

The lunar module was built exclusively to work in the vacuum of space, meaning that engineers could allow odds and ends to stick out from the body without worrying that any atmosphere would affect them. Avoiding the rounded edges seen in other spacecraft of the day helped NASA save a great deal of weight on the lunar module, eventually allowing astronauts to bring rovers and more equipment to the surface. The lunar module had two stages: a descent stage, which carried astronauts to the moon's surface, and an ascent stage, which returned them to the command module.

The lunar module was tested a few times in Earth orbit during crewed and uncrewed missions, but most lunar modules flew to the moon. Astronauts abandoned both the ascent stage and descent stage on the moon or in flight before returning to Earth. The exception was Apollo 13. When an oxygen tank exploded and damaged the command module, the crew swung around the moon and returned home using the lunar module as a lifeboat. That lunar module, called Aquarius, was discarded in Earth orbit, and unlike other lunar modules before it, this one burned up safely in the atmosphere.

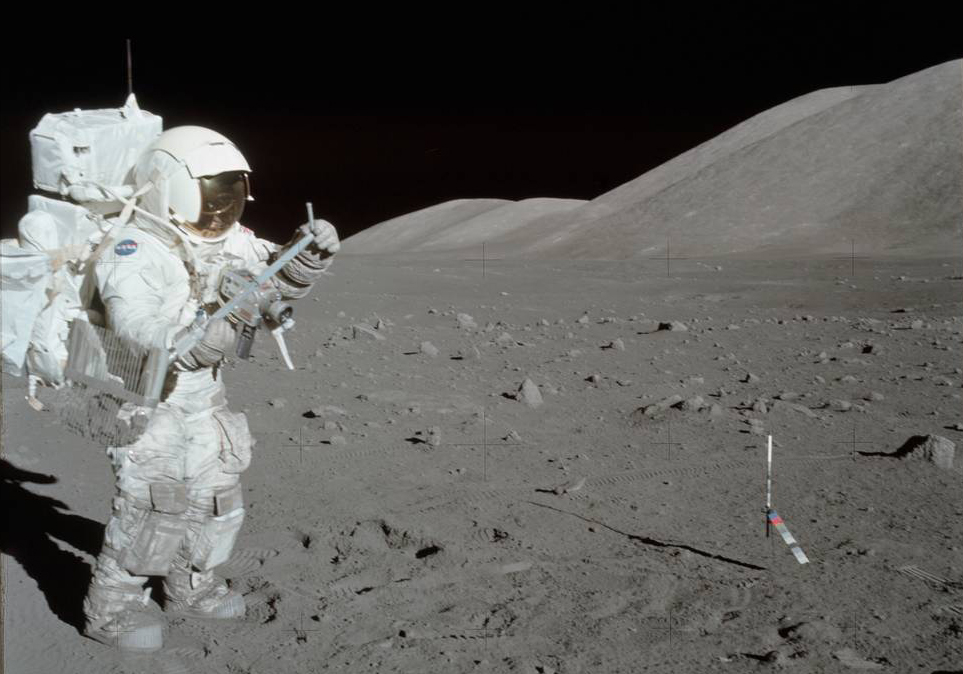

Apollo spacesuit

The most famous Apollo spacesuits were those designed for the lunar surface. These included several features for working astronauts: mobility in the arms and legs so the astronauts could move around as comfortably as possible, boots to withstand the harsh lunar dust, a portable life-support system (PLSS) backpack that carried needed oxygen and water, pouches to store science equipment, and many layers of insulation to protect astronauts against the harsh conditions of space (cold, radiation, sunlight and the like).

Launch

All Apollo rockets launched from the Kennedy Space Center near Orlando, Florida. (Pictured here is a Saturn V launched during an uncrewed mission, known as Apollo 4.) The command module, where the astronauts rode, is located near the very top and is dwarfed by the rest of the Saturn V structure. The Saturn V would push the astronauts into orbit, shedding two of its three stages as it went.

Once in Earth orbit, moonbound missions would fire the third engine one more time for the translunar injection. The lunar module rode to space in a conical structure mounted on the third stage of the Saturn V. After the astronauts arrived in orbit, they would turn around the command module and dock with the lunar module, pulling that segment out of the rocket's third stage.

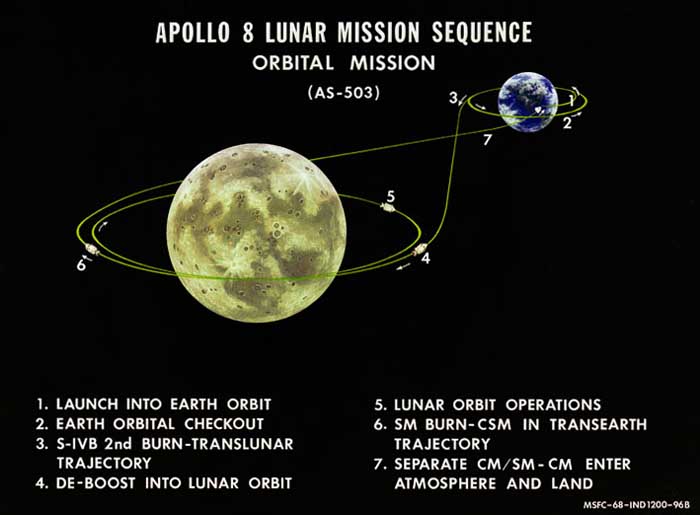

Cruise and moon landing

It took about three days for the astronauts to fly to the moon, and a typical mission profile (without the landing) is shown in this diagram for the Apollo 8 mission. Usually, the lunar module and command module would fly together to the moon. On the way, astronauts would do routine spacecraft maintenance, review checklists and power up the lunar module to make sure that it was ready for landing.

Landing

During lunar landings, two of the three astronauts on the mission would climb into the lunar module and undock for surface operations. Astronauts spent anywhere from one to three days exploring the moon during multiple spacewalks, while the lone astronaut in the command module remained in orbit and performed science observations. Astronauts' tasks on the surface, included collecting rocks, setting up experiments, driving the lunar rover and even testing the limits of mobility in their spacesuits.

The first human on the moon was Neil Armstrong, who landed with Buzz Aldrin on July 20, 1969. Ten other humans walked on the moon during Apollos 12, 14, 15, 16 and 17 (Apollo 13 skipped landing due to an in-flight abort, from which the astronauts returned safely). The last human on the moon was Eugene Cernan, who departed the moon (along with crewmate Harrison "Jack" Schmitt) on Dec. 14, 1972.

Return to the command module

When it was time for astronauts to go home, the lunar module would leave its descent stage on the surface and the astronauts would return in the ascent stage. The lunar module would dock with the command module once more; then, the lunar module's upper stage would be discarded and the command module would fire its engine to return home.

This picture was taken during Apollo 11 by command module pilot Michael Collins. In his later book "Carrying the Fire," (1974, Cooper Square Press) he mused that this was a unique picture taken of nearly all of humanity — the 3 billion people on Earth at the time and the two people inside the lunar module — absent only himself, the photographer.

Earth landing

Shortly before landing on Earth, the command module would discard the attached service module and bring astronauts back home through the atmosphere. The astronauts would be out of contact with the ground for several minutes during reentry, as atmospheric gases built up around their spacecraft. Once through the atmosphere, the command module would pop out parachutes to slow itself down. The final descent involved three large parachutes that would bring the command module down to an ocean landing.

The first three landing missions — Apollo 11, 12 and 14 — put the astronauts in quarantine after their return, in case of any lunar germs, a worry that abated after all three crews came back in good health. During those missions, the astronauts donned quarantine suits in their spacecraft before being hauled into a helicopter; later crews made the same journey without suits. A recovery boat would pick up the command module for later analysis. Today, command modules are displayed in museums and similar facilities around the world.

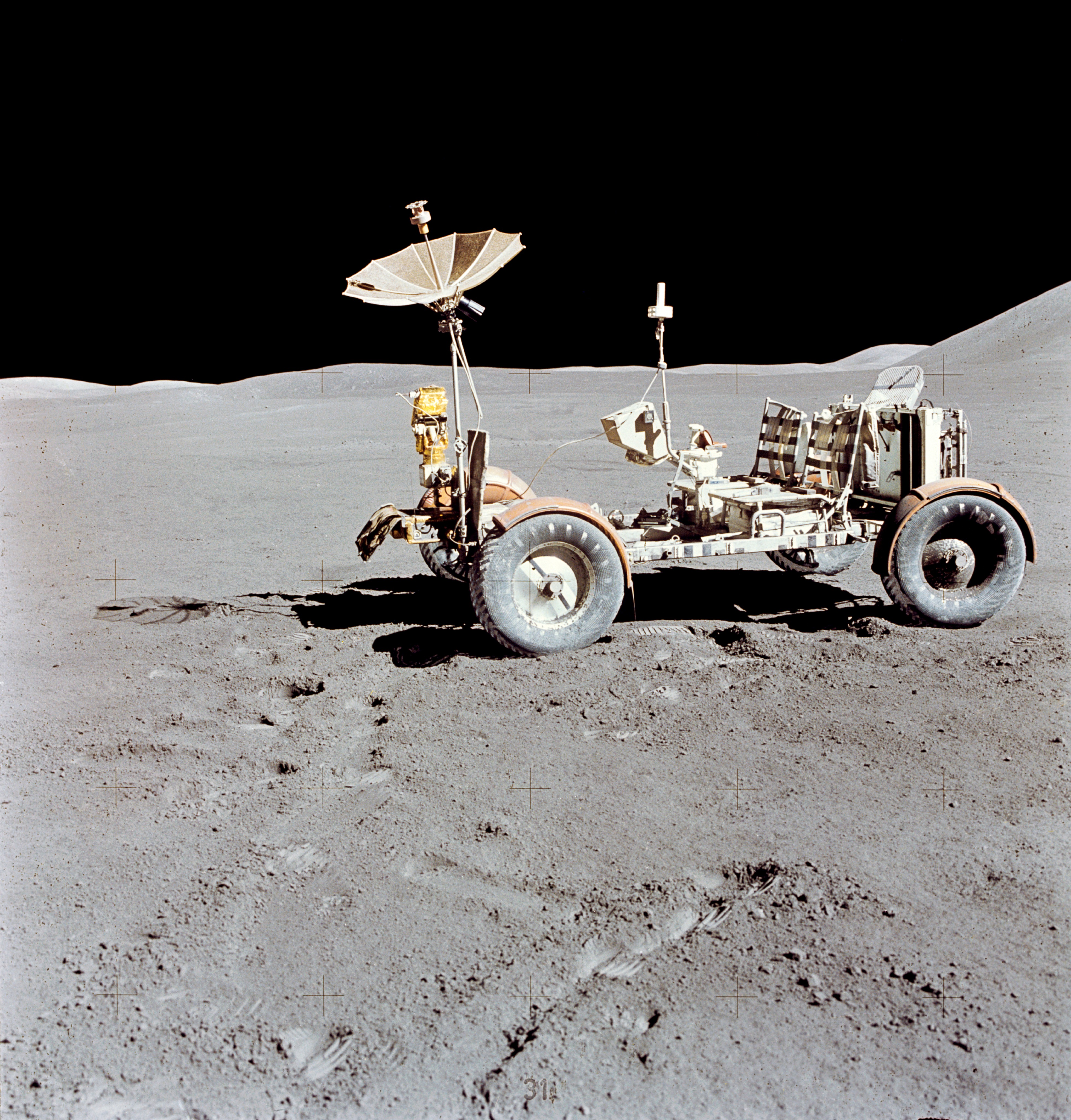

Lunar rover

The lunar rover allowed astronauts to travel farther on the moon than ever before. Rovers — which were carried to the moon on Apollos 15, 16 and 17 — brought astronauts several miles from their landers and provided extra storage space to carry equipment and lunar rocks. Driving was a challenge in the lunar gravity, which is one-sixth of Earth's. And on one mission, the abrasive lunar dust eroded away the fender, forcing the crew to construct a new fender out of unneeded lunar maps.

Spacewalks

Apollo is most famous for its moonwalks, but several astronauts performed extravehicular activities of a different sort. For example, three astronauts — including Ron Evans, pictured here during Apollo 17 in December 1972 — did "trans-Earth" spacewalks, or spacewalks during the phase when the mission was leaving the moon and going back to Earth. Evans and two other astronauts before him (on Apollos 15 and 16) retrieved camera film and scientific equipment from the outside of the command module to bring safely back to Earth.

Astronaut David Scott did a stationary spacewalk during Apollo 15 in July 1971 after the lunar module landed. For about half an hour, he stood in the top hatch of the lunar module and described the scene back to Earth, while taking photographs. The goal was to perform a geological survey of the site and to determine, from the ground, which areas might be best to visit during future moonwalks.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.